The passage begins with a description of how composers go about composing. Sometimes the music comes with such profusion that the artist cannot sleep, so beset he is with musical ideas. Then, in the cold light of day, the great inspiration of the night before vanishes, and the opposite problem arises, dearth. So the composer goes for a walk. Thereupon he accidentally whistles the perfect idea and is forced to run home through the town, bumping into pedestrians and leaving them in his wake, desperately humming the all-important tune, to burst through the door of his house and to record the precious melody before it vanishes. Why this story? Because that’s almost how he finished the “Cinq mai” cantata.

In the late 1820s, Berlioz was going through a full-on Napoleonic period. His arrival in Italy in 1830 to take up his Prix de Rome at the Villa Médicis coincided with the Carbonari uprisings (which also involved Hortense’s sons, Napoleon-Louis and Louis-Napoleon (future Napoleon III). Indeed, he was stopped at the border of the Papal States as being a suspect Frenchman. Academy students, Berlioz noted in his memoirs, were thought by the Italian police to have fomented the insurrection in the Piazza Colonna. As further evidence for his keen Napoleonism, Berlioz was present at Napoleon-Louis’s funeral in Florence, noting in his memoirs “Bonaparte! His name, his nephew; almost his grandson, dead at twenty!”. Continuing in this nostalgic vein, Berlioz was to make a pilgrimage to Lodi Bridge “even fancy[ing] that [he] heard the thunder of Bonaparte’s grape-shot and the cries of the flying Austrians.” Hector even wanted to visit Elba, Corsica and St Helena so as to “gorge [himself] on Napoleonic memories”. There were plans for a ‘military symphony’ on Napoleon’s return from Italy. The “retour des Cendres” was to make Berlioz annoyed that the music he had written for the victims of 1830 had not been used as a triumphal march ‘for the great hero’.

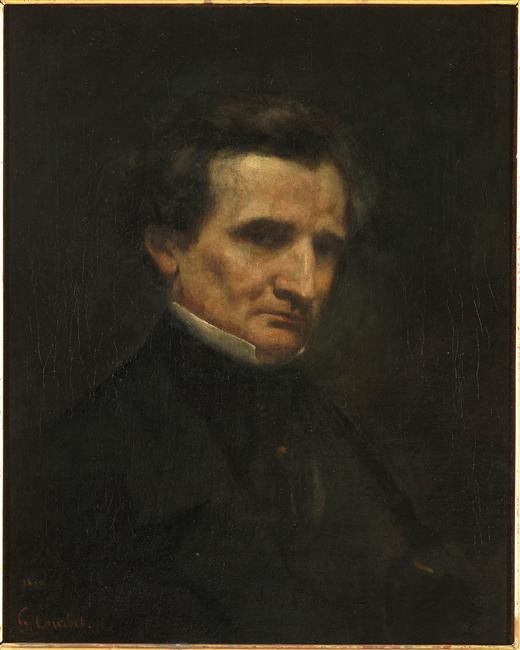

It was in this Napoleonic period that Hector penned the “Cinq mai” cantata and dedicated it to Horace Vernet, painter of Napoleonic battle scenes but also director of the Villa Médicis at the time.

However, as Berlioz records in his 1861 article, the completion of the work was not quite as epic as he would have liked. He had decided to write the cantata for orchestra and choir on reading Béranger’s poem, “Le Cinq mai”. The initial melodies came easily, he tells us, but the refrain – the most important part of the work with its words “Pauvre soldat, je reverrai la France, La main d’un fils me fermera les yeux.” – was proving difficult. Inspiration just wouldn’t come. He tried for a couple of weeks to knock it on the head, but finally abandoned the project. Two years later, in Rome, Berlioz went out for a walk on the banks of the Tiber. He slipped down the banks and thought he would soon be dead, drowned. To his surprise he found himself only ankle-deep in mud. As he extricated himself from the mire, the words (now comical) came to mind, with the perfect tune:

“ ‘Better late than never’ [Hector] cried”.

Dr Peter Hicks (2019)