These other celebrations were strategically timed and included everyone: the people, the army, the clergy, the state bodies and the nation’s elected representatives from all regions.

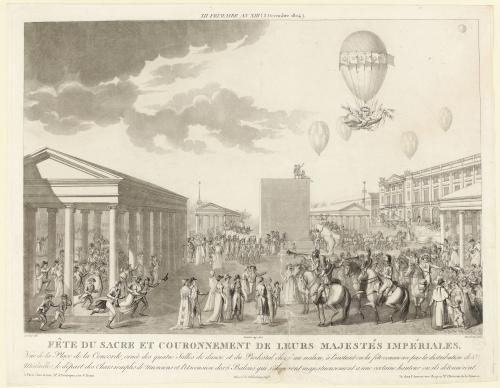

On 3 December, the festival was in the streets. The Place de la Concorde and all the boulevards were filled with impromptu dance halls (See the image below for the four temporary dance “temples” erected in Place de la Concorde); there were street theatres on trestles and greasy poles to climb (mâts de cocagne) (Also visible in the image below. Successful climbers could grab a ham/salami or other prizes suspended at the top.), etc. Carnival floats bearing musicians and “parades of Harlequins, Cassanders, Paillasses” (Histoire du couronnement ou Relation des cérémonies religieuses, politiques et militaires qui ont eu lieu pendant les jours mémorables consacrés à célébrer le couronnement et le sacre de Sa Majesté Impériale Napoléon Ier,… , par J. du Saulchoy avec la collaboration de J. Lavallée et de A. Coupé, 1805 à consulter dans Gallica ark:/12148/bpt6k64706999 Harlequin, Cassander and Paillasse were standard Commedia dell’arte figures transposed to France.) added to public amusements. Medals were distributed, and golden balloons ascended into the Parisian sky to which were attached eagles, garlands and laurel wreaths (the latter a sign of victory and joy), which exploded, scattering the attached decorations (See the image below for one of the five golden balloons). In the evening, Paris was illuminated, and a large firework display was set up on the Concorde bridge, with the dancing continuing for the rest of the night (Voir David Chanteranne, Le Sacre de Napoléon, Paris, éditions Tallandier, 2004.).

On 5 December, it was the army’s turn to celebrate, with the ceremony on the Champ de Mars of the “Distribution of the Eagles” to deputations from the army and the national guard. This event, “a reward for the devotion of the brave” (Histoire du couronnement cit.), was marked by great solemnity and included a tribute to the marshals. It was followed by a banquet and a concert at the Palais des Tuileries.

On 8 December, another high military point was the reception of deputations from the army and navy, numbering more than seven thousand men, in the galleries of the Napoleon Museum (future Louvre). Flanked by his brother Louis and his brother-in-law Joachim Murat, Napoleon devoted a great deal of time to those present: “he went from row to row…, stopping and speaking to each deputation as it was presented to him by the Connétable” (Ibidem.).

After paying special attention to his beloved army in anticipation of future military operations and at the same time buttering up Parisians by prolonging the festivities so as to ensure calm and loyalty, then came the time for the presentations, in other words, the receptions of all the bodies of state, the clergy and the elected representatives. These audiences followed one another at a frenetic pace several times a day. For ten days or so, all cogs in the human “engine” of the Nation presented themselves to Napoleon, and he carefully received them with all the pomp and circumstance of his condition as Emperor. He made a show of being close to those presented and being accessible to them as a listening ear. The stakes were high; during these privileged meetings, loyalty to the new regime and to Napoleon’s person as Emperor, and beyond that, the hope of his legitimacy, was in the balance. As a sort of backchannel, these sessions were the best means for Napoleon to communicate his hopes for the future of the Empire.

The list of participants was significant: first to be received were the bishops and archbishops of the Empire, followed by the marshals, generals, grand officers of the Empire, admirals, members of the court of cassation, presidents of the courts of appeal, members of l’Institut, presidents of the electoral colleges, including the prefects of the 108 departments of the Empire, presidents of the Conseils Généraux, mayors of the 36 towns, presidents of the cantons, presidents of the consistories, etc.

In addition to the festivities, the presentations were undoubtedly unforgettable moments for many, particularly for the elected representatives of the regions and the soldiers from all over France.

In the evenings, receptions of hundreds of guests vied with each other in their sumptuous decorations and jeux de lumière amidst banquets, theatre shows, concerts, balls and firework displays.

Paris glittered in these exceptional festive moments. On 13 December, for example, the Senate offered a celebration in the Luxembourg Gardens: military music, dances, illuminations, the highlight of which was a firework display with a volcano at the heart of which rose an effigy of the emperor crowned with the genius of Victory.

On 16 December, the reception at the Hôtel de Ville in Paris was the climax of this series of events. On the one hand, street Parisians were offered entertainments including street music, tombolas, street food (notably poultry), wine fountains. On the other, the invited guests gathered in the Throne Room of the Hôtel de Ville and then took a collation in the surrounding galleries, “girandoles blazing with the fire of a great number of candles were hung over the centre of these tables” (Ibidem.). Napoleon and Josephine received gold and silver medals bearing their images, as well as a luxurious vermeil table service including two decorative table-centre “nefs” (literally boats, the symbol of Paris being a ship), masterpieces of silverwork .

As an epilogue, after this “out-of-time” period marked by glorious celebrations and the hope of a legitimacy forged during the presentations, Napoleon, now Emperor, found himself facing his new destiny. And so, at the end of December 1804, the history of his reign and of the Empire could begin.

Claude Collard, 2 December 2021 (translation Peter Hicks)

Claude Collard is an honorary Conservatrice Générale des bibliothèques.