Whilst quite naturally the Japanese had no difficulty receiving Western advances in the sciences and geography via the Dutch, information on politics and culture was a more delicate matter. The importation of western documents of this sort was a laborious, even dangerous task, and possession of them by those unauthorised was harshly punished. That being said, some non-scientific data did penetrate. In the late 18th century, the captain of a Japanese ship wrecked off the coast of the Russian island Aleutia, Daikokuya Kodayu, ‘visited’ Catherine the Great’s court. Prevented from returning to Japan (because of Sakoku) but also not allowed to leave Russia, he wrote an extensive diary of life in Russia, thereby providing the first links between the two countries. Russia would likewise later be the first source of the first information on Napoleon. The Russian explorer, captain Golovnin, foundered off the coasts of Yezo (Hokkaido today), was captured in 1811 and not released until 1813. A crewmate, Fedor Mur, who wrote of their capture, was found in possession of newspapers and information about the west which were seized. These documents were delivered to the Tenmonkata, an organisation created by the government to study the west, and fell into the hands of the scholar Takahashi Kageyasu. It is said that Takahashi at that time translated a small biography of Napoleon and wrote on the Battle of Waterloo.

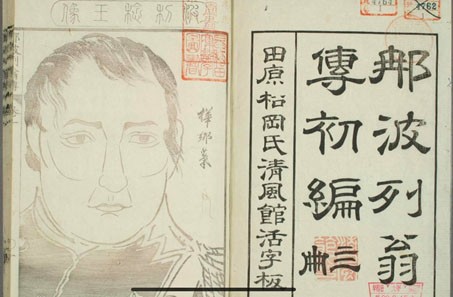

Later on in the century (the work was finished in 1837), an early Dutch language biography of the First Consul until the peace of Amiens Het Leven van Buonaparte written by Joachim Van der Linden and published in 1802 (itself compiled from several French and English sources (notably the English Biographical anecdotes of 1797 and Charles-Yves Cousin d’Avallon’s anonymous Histoire de Bonaparte, premier consul (An IX but 1801)) was to be translated into Japanese by Kouseki San’ei. Though it is unsure whether Kouseki San’ei had any knowledge of Kageyasu’s earlier work, the text was not to be published in Kouseki San’ei’s lifetime but in 1857 under the title Naporeonden (那波列翁伝 i.e., Life of Napoleon”), eighteen years after his death by suicide. In this period, Japan had become more hostile towards the west, perhaps explaining the relative absence of contemporary documents on Napoleon.

Since the Japanese is a word-for-word translation (right down to the footnotes) of Van der Linden’s book, we know then that Japanese scholars had a very positive (and relatively accurate, it must be said) idea of who Napoleon was and what he was doing in Europe shortly after the Coup d’état of Brumaire. That being said, none of the images present in the Dutch publication were reproduced, and the 1802 portrait engraving of Napoleon First Consul was to be replaced by an image of Napoleon Emperor.

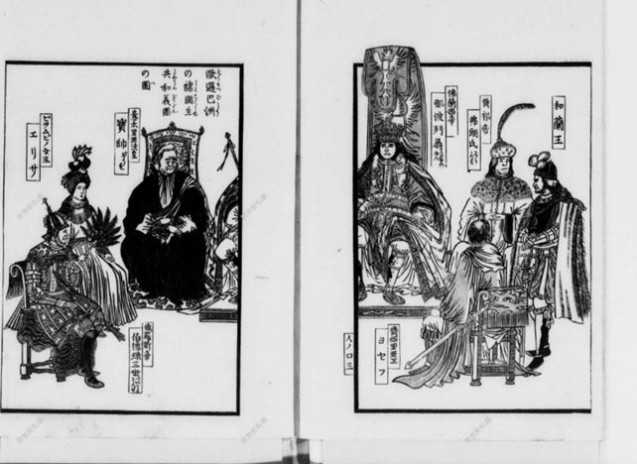

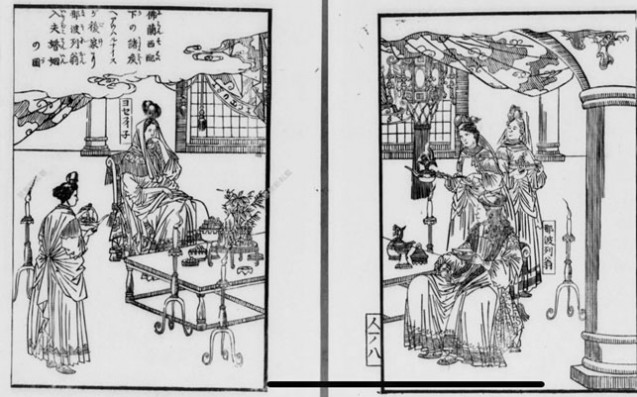

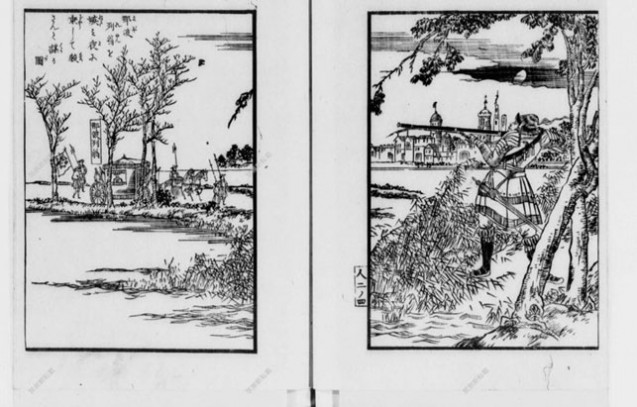

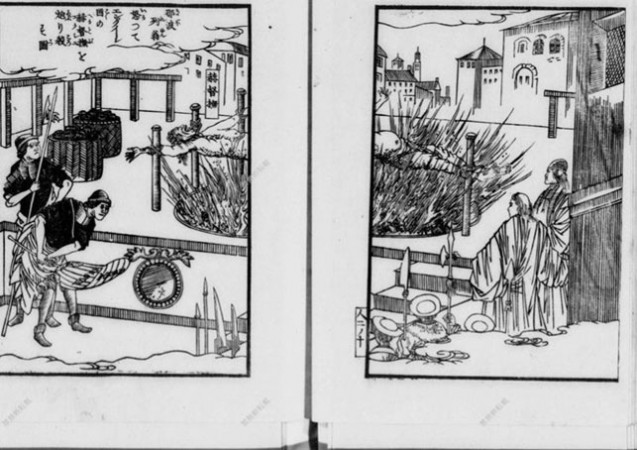

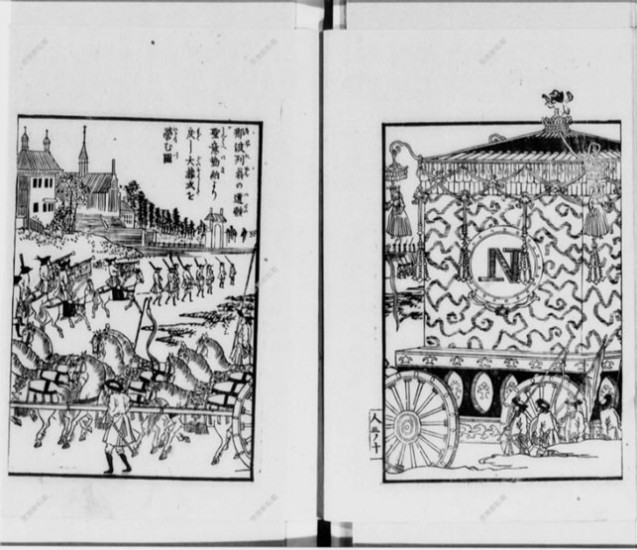

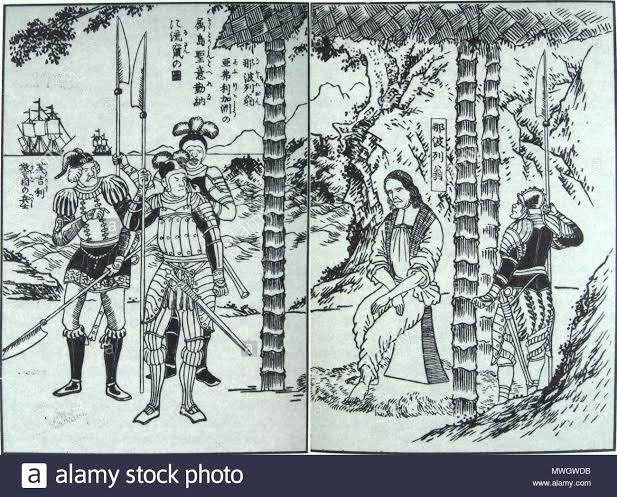

In complete opposition to the accurate Western version of the life of Napoleon (though only up to 1802) is the work entitled The small book of foreign people (海外人物小伝). Published in 1853 (one year before the opening to the West and four years before the biography), as can clearly be seen from the well-known Japanese woodcut of Napoleon imprisoned on St Helena. In this completely “Japan-ised” image, those taking Napoleon prisoner are portrayed as almost medieval Japanese warriors, and Napoleon is dressed as an 18th-century Dutch pastor. Most interesting of all however are the captions. Napoleon’s name features in Chinese characters 那波列翁 to be read as Na-po-re-on, a series of characters also found on the title page of the translation by Kouseki. The same is true for the name of the island 聖意勒納 Sen-to-he-re-na. The implication here is that the story of Napoleon had been studied enough to have an established a “Japan-ised” version of his name and of the island. Although the book is inaccurate in its drawings, it has made an attempt to provide a complete version of Napoleon’s life, from birth to death. “The small book of foreign people” comprises biographies of three figures of world renown, Napoleon, Alexander the Great, and Tsar Alexis I – though that on the French Emperor occupies two-thirds of the book (69 pages out of 106). Napoleon is thus here shown as one of the great heroes of Europe. His reputation is glorious, his exploits are revered, and the episodes in his life (though the representations are quite distant from reality) were clearly thought to be spectacular, as can be seen in the woodcuts (a selection shown here). In 1853, during the reign of Napoleon III, Napoleon I had become ‘big in Japan’!