Probably the most famous equestrian statue of Joan of Arc [Jeanne d’Arc] is the one by Emmanuel Fremiet, erected in 1874 on the Place des Pyramides and which has become a veritable Paris landmark. And this is but one example of the omnipresent place that Joan of Arc occupies not only in French public space but also more broadly in the French national narrative. It is however often forgotten that this image of Joan of Arc as a national heroine emerged from the political and social upheavals of the 19th century. The myth of a Joan of Arc embodying, for French minds, heroism, courage and freedom, was largely fashioned during the First and Second Empire.

It is a fact however that the political appropriation of the figure of Joan of Arc has little to do with the historical reality of the medieval period. It is above all an image constructed by and for the 19th century, during the rise of patriotism in France and subsequently French society’s needs to define its identity. As a result, the image of Joan of Arc in the Napoleonic period is similar to that of the ‘great men’ of the 19th century. Most often, she is depicted as a young warrior, victoriously mounting her horse and firmly holding her standard or sword. While several great figures of the Middle Ages carved out a place for themselves in the national narrative in the 19th century, such as Clovis, Charlemagne and Saint Louis, there is something about Joan of Arc that particularly marked the French imagination. However, nothing in the 15th century could have foreshadowed such a reputation…

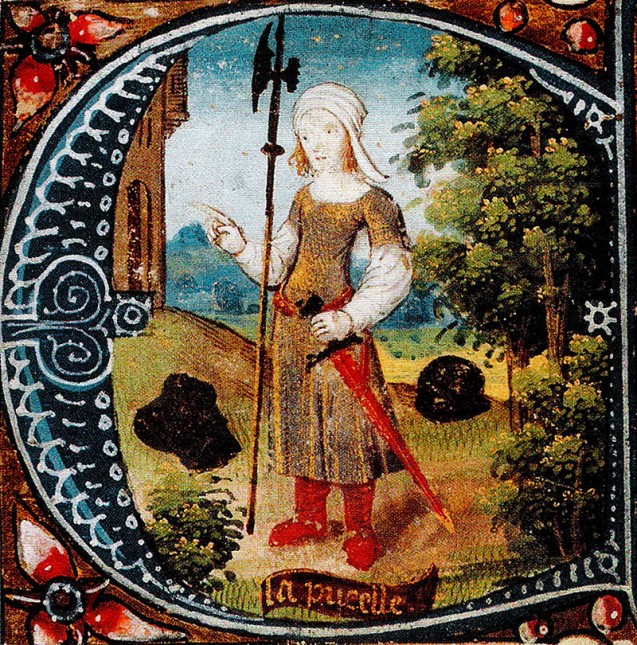

Joan of Arc was rarely the subject of iconographical representation at the time of the events (c. 1412-1431): we know of only a few, subsequent illuminations or lettering dated from the 15th century. After a period during the Enlightenment and the French Revolution when her legend was almost effaced, from the Consulate onwards the great ‘rehabilitation’ of the cult of Joan of Arc took place in the collective memory of the French. Napoleon, at that time First Consul, re-instituted in 1803 a celebration of the May day on which Joan of Arc liberated Orleans (8 May 1429), city besieged by the English during the Hundred Years War. In his official request or Decision regarding the re-establishment of the “fête”, the First Consul remarked: “The illustrious Joan of Arc has proved that there is no miracle that the French genius cannot work when national independence is threatened. The French nation has never been defeated; but our neighbours, abusing the frankness and loyalty of our character, constantly sowed among us those dissensions from which arose the calamities of the time when the French heroine lived, and all the disasters which our history recalls.(Correspondance de Napoléon Ier publiée par ordre de l’empereur Napoléon III, t. 8, Paris, Henri Plon – J Dumaine, 1861, p. 196-197.). A year later, on 7 May, a statue of Joan of Arc by the sculptor Edmer-François-Étienne Gois was inaugurated on the Place du Martroi in Orléans (funded by the First Consul). In 1855, local Orleans elites judged the statue insufficiently imposing and replaced it with another by Denis Foyatier.

In the minds of contemporaries, a relationship began gradually to be forged between the fates of Napoleon and Joan of Arc. Both were recognised for their military prowess and their sacrifice in the name of the French nation, but above all both were victims, indeed ‘martyrs’, of the English.

The fascination of the French people of the time for the tragic fate of the young ‘shepherdess’ (who was in fact neither a shepherdess nor illiterate…) betrayed by her king and burned by the Church was therefore overwhelming. The number of publications on her story in the first half of the 19th century bears witness to this. Already before 1820 had appeared Histoire de Jeanne d’Arc, surnommée la Pucelle d’Orléans by Philippe-Alexandre Le Brun de Charmettes (1817) and Jeanne d’Arc à Rouen by Charles-Joseph Loeillard d’Avrigny (1819). It was however Jules Quicherat’s Procès de condamnation et réhabilitation de Jeanne d’Arc, published between 1841 and 1849, as well as the chapters devoted to her by Jules Michelet in his Histoire de France (1833-1844), that permanently integrated Joan of Arc into the national narrative. In no time at all, she made her entry into school textbooks. However, it was above all the theatre, with 80 plays produced throughout the 19th century, that brought to the attention of the general public in France a multi-dimensional Joan of Arc: Joan the mystic, Joan the heretic, Joan the warrior, but above all Joan the heroine with boundless courage and determination.

The patriotic exaltation around the figure of Joan of Arc was reflected in the artistic production at a time characterised, as we know, by its obsessive “statuomania”. From the Second Empire until the First World War, many artists, painters, sculptors and engravers worked to create representations of her. Joan thus gained a dominant place in the public space. Why precisely at this time? The turning point came with the defeat of Sedan in 1870 and the fall of Napoleon III, which led to a real instrumentalisation of the image of Joan. The trauma of the defeat in France by German troops was a catalyst in the creation of the image of Joan of Arc as an emblem of the ‘resistant’ nation. It spread throughout the country: each town wanted its own version of Joan.

Here the young woman’s link to Lorraine is obviously particuarly significant, as she comes from the small Lorraine village of Domrémy, now called Domrémy-la-Pucelle [“La Pucelle” was the nickname given to Joan of Arc]. The shock of the ‘loss’ of the Alsace-Lorraine provinces to the Germans made her a symbol of opposition to the invader, which imposed itself. From then on, it was no longer a question of the English, but of the Germans. Statues of Joan of Arc, multiplied after the Franco-German war, quickly lining the border. There are almost 75 statues of Joan of Arc, victorious, all facing Berlin, which show, by the strength of the image and the presence of the statuary, France’s opposition to Germany.

The Germanophobic climate in France at the end of the 19th century reinforced the political and national symbolism attributed to Joan of Arc. After the Second Empire, the symbol of Joan was recuperated not only by Republicans, but also by the Church. She was recognised as venerable in 1896, beatified in 1909, and canonised in 1920 by Pope Benedict XV. A national holiday was proclaimed in 1920 commemorating the liberation of Orleans from the English, one again underlining how this historical figure was the expression of patriotism and freedom in the face of oppression.

We are here light years away from the scornful image of Joan of Arc produced by Voltaire in his Pucelle d’Orléans [maid of Orleans] in 1762. But what an unexpected destiny for this young woman, of modest origin, who was in the news for only 2 or 3 years in the Middle Ages! Later, in the 20th century, cinema made her one of the most represented historical figures along with Napoleon. It is impossible to forget the tearful look of Renée Maria Falconetti, playing Joan of Arc in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent film La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Even today, in 2021, more than 100 years after her canonisation, the symbol of Joan of Arc is still potent, but the uses are changing: sometimes an icon reappropriated by feminist movements, sometimes recuperated in France by the nationalist right, she acts as touchstone for new political divisions. But our view of the past must do justice to the founding role of the Napoleonic periods in the construction of Joan of Arc’s image in the public space and the French people’s passion for her story.

Amélie Marineau-Pelletier, November 2021 (English translation PH]

Amélie Marineau-Pelletier PhD was web-editor at the Fondation Napoléon (July-November 2021)

► Further reading

•COLLARD, Franck, La passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Mémoires françaises de la Pucelle, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 2017.

•KRUMEICH, Gerd, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l’histoire, préface de Pierre Nora, Paris, Belin, 2017.

•NADINE-JOSETTE, Chaline, “Images de Jeanne d’Arc aux XIXe et XXe siècles”, in François Neveux (dir.), De l’hérétique à la sainte : Les procès de Jeanne d’Arc revisités, Caen, Presses universitaires de Caen, 2012, p. 273-284.