He quickly got himself an interview with Daru, “intendant général de la Couronne”, and informed the administrator that he would love to be able to take care of the little-used imperial library: “I am so crazy about books that I would run through fire or jump into the sea to save a good one”(je suis si fou des livres que je me jetterais, je crois, à travers les flammes ou au milieu des flots pour en sauver un bon https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/media/FRAN_IR_051115/c-a1xywn74f–a8h0b1pf8xzn/FRAN_0013_043255_L)”. Daru must also have been aware of his principal book, which has remained notorious among collectors of subversive works and not the kind of book to be left lying around! (La Chézonomie or the art of shi*****. : a didactic poem in 4 songs https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k11841340/f12.double)

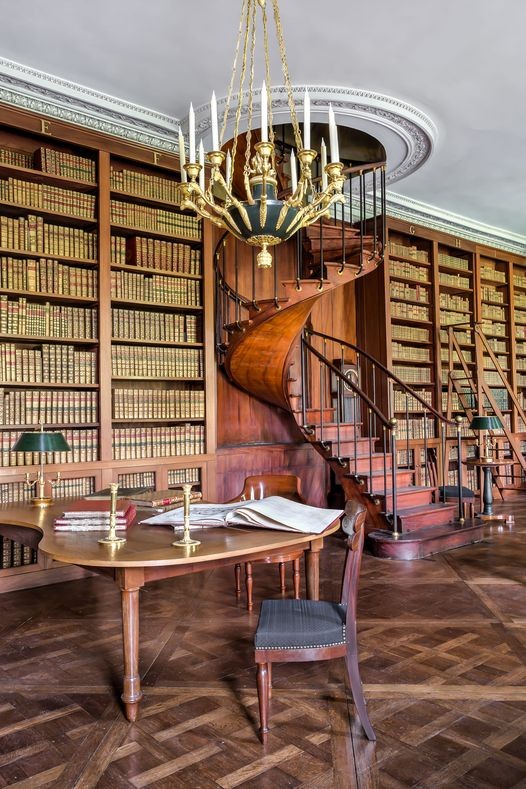

Having convinced Antoine-Alexandre Barbier, Napoleon’s fastidious private librarian, Rémard managed to get himself a permanent job, beginning on 1 January 1811, as caretaker of the 30,000 volumes held in the master’s “cabinet particulier” (private study), established in 1808, and in the former Chapelle Saint-Saturnin that had been refurbished as a library for the imperial court. Rémard in the end was not a great appointment in that he was one of those librarians who preferred to read books rather than look after them: the rotting tomes piling up in the Emperor’s study did not seem to worry him much, and the inventories were rarely kept up to date. He was content to have books to browse through and a nice appartment that came with the job, and, apart from enjoying these priviledges he did not actually do much except bicker with the concierge and occasionally boss around the palace staff whose job it was to beat the books to remove the dust. He had little direct contact with Napoleon, but his big assignment from 1812 onwards would be to supply books in order to keep Pope Pius VII occupied while he was detained at the chateau. In particular, the pontiff had the opportunity to peruse a thick Histoire de l’Église [History of the Church] by Berault-Bercastel.

From 16 to 18 February 1814, Rémard was distraught when the Russians turned up and briefly occupied Fontainebleau and stole maps from the Emperor’s topographical cabinet, but he did manage to prevent the library from being pillaged. Two months later, after the first abdication, he carried out Napoleon’s orders without question by finding and packing the books to be sent to Elba (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10089797r/f60.item Papers of Antoine-Alexandre Barbier and Louis Barbier. XXXIII State of books removed in 1814 and 1815 from the libraries of Saint Cloud, Compiègne and Fontainebleau. Catalogue of the books of the cabinet at the Louvre library).

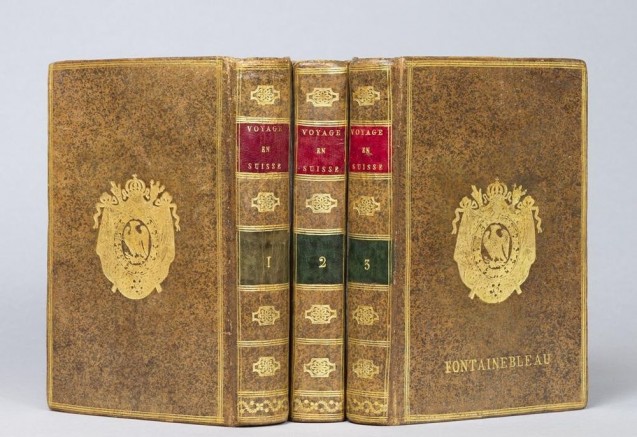

These volumes, from the Fontainebleau library, were among those taken by Napoleon to Elba in 1814.

As soon as Louis XVIII was back in power, Rémard inundated those close to the king with entreaties, seeking at all costs to keep his job, even claiming to have fought in defence of Louis XVI on 10 August 1792 in the Tuileries(https://www.enssib.fr/bibliotheque-numerique/documents/52303-charles-remard-poete-et-bibliothecaire-1766-1828.pdf). In addition to his devotion to the Pope, he had a rock-solid argument: since the position of librarian of Fontainebleau had been abolished by Louis XIV before being reinstated by Napoleon, he could not be guilty of having taken the place of any emigrant [from the Ancien Regime]!

Having definitively lost his admiration for the Emperor, Rémard actually hid when Napoleon passed through Fontainebleau again on 20 March 1815 before making his triumphal entry into Paris. A few months later, Rémard managed to minimise pillaging during the Prussian occupation of the château after Waterloo. In 1820, he published one of the first tourist guides to the château, in whose pages one would be hard pressed to find even a mention of the “Usurper”, and went on to serve the Bourbons loyally until his death in 1828 (thus he missed out on the chance to change his allegiance one more time by serving Louis-Philippe).

The remarkable restoration of the library, completed in Spring 2021 just in time for the reopening of museums here in France, has given me an opportunity to pay tribute to this not very competent but courageous librarian, to whom we owe the fact that most of the books assembled for Napoleon in the library at Fontainebleau are still there on the same shelves, two centuries later, a true and unique testimony to the Emperor’s literary tastes and working practices.

Charles-Éloi Vial

June 2021 (translation RY ed. PH)

Charles-Éloi Vial is an archivist and paleographer, a Phd in history, and a curator at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. He received the 2017 First Empire History Prize from the Fondation Napoléon for his biography of Marie-Louise (Perrin). His next book, to be published on 26 August 2021, will be about Napoleon and libraries during the First Empire Napoléon et les bibliothèques – Livres et pouvoir sous le Premier Empire (co-published by Perrin and CNRS Éditions).