The military hairstyles of the French Revolutionary Army were almost as catastrophic as the hairstyles some people have been fashioning for themselves during lockdown. From 1792 onwards (once the euphoria of the early days of the Revolution had abated), military haircut regulations were introduced; soldiers were to wear their hair long and in a ponytail. Hair had to be cut short, and sideburns were not to grow below the middle of the ear. The ponytail was considered useful against sabre blows, and was not to exceed the respectable length of eight inches (21.6 cm). It was to be covered in a black wool ribbon, and in some army units it was to be bleached.

However, time constraints meant that the regulations could not be properly enforced, which led to all manner of hairstyle variations. Catogans (a low ponytail at the nape of the neck) and cadenettes (plaits worn at the temples, normally by light cavalrymen) of all lengths and widths could be seen on the soldiers, as well as coupes à oreille de chien (hair worn in curls over the ears) and even wigs on the officers. Adherence to the regulations, and therefore hairstyle variation, depended on the chefs de brigade [the military rank equivalent to colonel] and their enthusiasm for enforcing military laws. With the Consulate came renewed efforts to regulate military hairstyles, and soldiers were to have their hair cut short and bobbed.

By this time, it was the norm for civilian men and women to to wear their hair short (They followed the revolutionary/’post’-revolutionary trends of à la titus [in the style of Titus – in imitation of the busts of Roman emperors, done as a celebration of democratic antiquity] or “coiffure à la victime [in the style of the victim – hair cut short as an homage to those who had lost their lives to the guillotine]), but in military spheres the regulation haircut of 1792 (when it was enforced) prevailed. Many military hygienists called for new haircut regulations, believing that the ponytail represented nothing more than coquetry, and unnecessarily took up a large proportion of a solider’s time and money (as it required daily maintenance). Powdered hair also caused problems in wet weather, dirtying uniforms and eventually causing them to deteriorate.

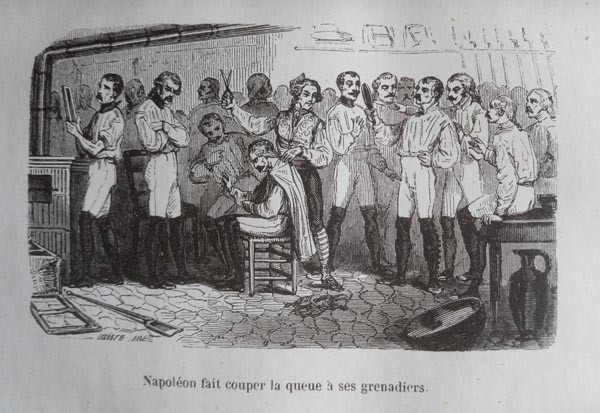

In 1804, Bonaparte took these recommendations on board, and a new regulation was introduced to limit the number of Imperial Guard units that were allowed to wear ponytails. For line infantry, it was now compulsory to cut their hair short and to ensure that nothing was covering their ears. Napoleon preferred not to force regulations on his soldiers, and almost favoured voluntary service. He found it difficult to enforce the new regulations, even among the highest military ranks. The light cavalrymen (hussars and chasseurs à cheval [mounted chasseurs]), whose ponytails and cadenettes were an integral part of their regiments’ identity, proved to be the most recalcitrant. Out of a sense of masculine pride, and perhaps a strong esprit de corps, men with short hair (les caniches [poodles]) and men with long hair would sometimes duel to determine who was the bravest… and best coiffed!

In 1806, the units who had refused to change their hairstyles were formally ordered to comply with the new regulations. The men of several units had their catogans and cadenettes cut, sometimes in an almost ceremonial manner (as in the case of the 5th hussars, who had refused to conform for a long time). Most of the cavalrymen were deeply upset, as they saw it as a loss of identity.

During Napoleon’s Empire, the commanding officers retained some autonomy, and whether infantrymen and cavalrymen wore their hair long or short depended on their unit. For example, in Spain, Colonel Lelievre de la Grange of the 15th Regiment of chasseurs à cheval let his favourites (the dragoons) grow their hair long, but made the rest of his men cut their hair short, while his successor in 1812 ordered his men to shave but to let their hair grow long. This lack of uniformity between units lasted until the end of the Empire.

Before they were allowed to choose their hairstyle, new conscripts were shorn and shaved (if necessary). This was carried out in the name of hygiene and uniformity, and also made it easier to tell the difference between the new soldiers and those who had already been trained. The distinctive nature of the hairstyle also made it more difficult for men to desert, making it easier for the gendarmes to find men who had run away. During the recent lockdown, this “conscript” haircut became the trend for those who were too impatient to wait and have their hair cut professionally. With the easing of restrictions, will the catogan make a comeback?

May 2020 (translation JR)

François Houdecek is responsible for special projects at the Fondation Napoléon.