Against the immense forces of the army in front of him, MacMahon ordered the army corps to position themselves close to the town’s 17th-century citadelle. Almost simultaneously, before dawn on 1 September, the Bavarian troops under the command of Ludwig von der Tann pursued and surrounded the French forces at Bazeilles, while the 3rd and 4th German armies (commanded by Prince Frederick William of Prussia and Prince Albert of Saxony respectively) moved down from the north in order to break through the first French line of defence before converging and making their advance towards the Plateau d’Illy, where General Margueritte’s 1st Reserve Cavalry Division was positioned. At around 4 o’clock in the morning, some Bavarian units had successfully infiltrated Bazeilles and were approaching the Château de Sedan but they were met with resistance from the Division Bleue [the Blue Division] of French marsouins [marine troops], giving momentarily a slight advantage to the French.

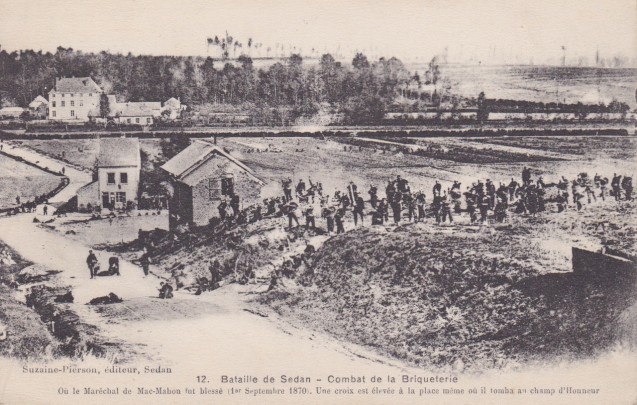

However, at 7am the French were dealt a blow: the Duke of Magenta received a serious shrapnel wound to the thigh, forcing him to abandon his command (an event that saved him from the humiliation of having to sign the treaty of surrender once the fighting had ceased). His replacement, General Ducrot, immediately ordered his forces to retreat to Mézières, a move he believed would be their only chance to remove themselves from the ‘pincer’ of the German forces and to organise a counteroffensive. At this point, the movements of the French army were interrupted by a letter sent to Ducrot by General de Wimpffen. Citing a directive from the War Minister the Comte de Palikao, de Wimpffen demanded interim command of the Army of Châlons, should MacMahon be unable to perform that duty.

De Wimpffen then countermanded Ducrot’s orders. The French Army was now confused by the series of different orders it had received from three successive commanders, and marched almost blindly following simply the most recent orders. At around 1pm, de Wimpffen launched a large-scale counter-offensive on Bazeilles. His aim was to open the road to Metz, and he ordered Ducrot and Douay’s reserve divisions to leave the northern front to join the assault. Although the marsouins once again distinguished themselves by pushing back von der Tann’s Bavarian forces, their actions were undermined by the tactical errors of the French headquarters.

The French commanders were severely disorganised amongst themselves and their lack of maps made their troop movements faulty. As a result, some men found themselves on the wrong paths, while others were needlessly exposed to artillery and suffered considerable losses. The French lost ground and were disoriented and under constant shellfire. The Bavarian Fourth Corps managed to breach the French defence and successfully cut the French Imperial army in two between Bazeilles and Sedan.

The fighting at Bazeilles was extremely bloody, and although the French troops of the Division bleue were outnumbered ten to one they fought house-by-house to hold the village. The French resistance finally broke as the marsouins were overwhelmed by the ever greater numbers of German troops. And yet, in the face of inevitable defeat, and with the help of armed civilians, the French refused to surrender but fiercely defended every last bit of ground. Under the constant, deathly fire of the German artillery, and surrounded by spreading flames and the deafening sound of collapsing houses, the Emperor’s troops gradually gave in, as their ammunition began to dwindle and their limbs were paralyzed with fatigue.

Meanwhile, the fate of the entire battle was sealed at the village of Donchéry – a crucial point for the French battle plan. The 3rd and 4th Prussian Armies were able to successfully surround and capture the French Army in a funnel-like formation. De Wimpffen had his attention completely focused on the northern front, and did not notice the movement of his troops at the rear. The two Prussian armies were therefore able to join up and take the French from the behind. At this point, any idea of an orderly retreat became impossible, and the Prussians were able to move into the gap that was forming between the corps commanded by Douay and Ducrot. Faced with this alarming turn of events, General Margueritte threw his horsemen in a cavalry charge – as momentous as it was desperate – in the vain hope of breaking through the encirclement of troops around the Plateau d’Illy.

From his vantage point on the heights of Frénois, King Wilhelm watched Margueritte’s cavalrymen hurl themselves into the carnage, and spoke the now famous words, ‘Ach die tapferen Leute!’ [Ach, what heroic men!].

It was carnage. Panic swept through the French ranks, and troops took refuge in the fortress of Sedan in the vain hope of escaping German cannon and gun fire. A stampede ensued, with soldiers, horses and wagons bottled up in front of the drawbridge to the fortress, and amidst the groans of the dying and the shouts of the survivors men ran pell-mell for their lives. German artillery shells wreaked havoc on the French units entrenched in the fortress, starting numerous fires along the way, and the rank and file of the French Army began to threaten the officers who were taking the best shelters for themselves. The Emperor’s staff and circle of high-ranking officers urged him to surrender, while de Wimpffen alone continued to persist in rallying his troops, who were now clearly more concerned with their own survival than that of the Empire.

The Emperor understood that the situation was hopeless, and turned his attention to halting the bloodshed. He decided to have himself taken as prisoner, hoping to spare his generals the humiliation of surrender, and to save the lives of his troops. He made the order to raise the white flag at the top of the fortress, but it was soon removed under the orders of General Faure who believed he was only under obligation to follow de Wimpffen’s commands (yet another instance of catastrophic communication characteristic of the French command during the the battle). The Emperor quickly had the flag raised for a second time.

At 6 p.m., the Emperor asked his aide-de-camp, General Reille(General Reille would see the fall of the Second Empire, just as his father had seen the fall of the first, fighting at Waterloo.), to convey the following message to King Wilhelm:

‘Monsieur mon frère, n’ayant pu mourir au milieu de mes troupes, il ne me reste qu’à remettre mon épée entre vos mains.’ [Not having been able to die in the midst of my troops, it only remains for me to place my sword in your Majesty’s hands.]

The Prussian king read the French Emperor’s letter at Frénois (he hadn’t moved from his position since the fighting began) and, after a short council of war held then and there with his general staff, accepted the Emperor’s surrender and appointed his commander-in-chief, General von Moltke, to act as his representative and draw up the treaty of surrender. As for Napoleon, he sent de Wimpffen to meet with Wilhelm’s staff at Donchéry, hoping to negotiate some of the terms. His hopes were dashed when von Moltke and Bismarck presented a summons for an unconditional surrender.

At 8am the following day, the Emperor climbed into the carriage that would take him to meet Wilhelm’s headquarters. The chancellor Bismark learned of his departure and set out to meet Napoleon halfway. The two escorts met at the commune of Mézières, where the French Emperor and Bismarck began discussions in the house of a weaver. Understanding that the Emperor hoped to gain certain accommodations from Wilhelm (a possibility, given the cordial nature of their relationship), Bismarck informed him that he would only be able to meet the Prussian king after he had signed the unconditional surrender.

De Wimpffen and von Moltke signed the act of surrender at around noon, in the presence of both the Emperor and the King of Prussia. Under the terms of the surrender, the French Army was to deliver all of its flags, cannons, equipment, weapons, and ammunition, as well as the fortress, to their opponents, and 80,000 prisoners were to be taken to the Presqu’île d’Iges [the Iges Peninsula] where they would be kept in what came to be known as the Camp de la Misère [the Camp of Misery]. The Emperor was forced to leave France on 3 September 1870 and was never to return. He was imprisoned in Wilhelmshöhe Castle, where he learned of the downfall of his Empire and the proclamation of the new Republic made by Léon Gambetta on 4 September. Sedan had become to him what Waterloo had been to his uncle, Napoleon I. From then on, France would only ever be a Republic (With the exception of the Vichy Government from 1940 to 1944.).

Eymeric Job, July 2019, trans. JR with PH

Sources

- Jan Ganschow, Olaf Haselhorst, Maik Ohnezeit, Der deutsch-französische Krieg 1870/71. Vorgeschichte-Verlauf-Folgen, Ares-Verlag, 2009

- Eric Anceau, Napoléon III, un Saint-Simon à cheval, Tallandier, 2008

- Pierre Milza, Napoléon III, Perrin, 2006

- François Roth, La guerre de 70, Fayard, 1990