The emergence of Prussia as a hegemonic power

At the dawn of 1870, Prussia (under the rule of King Wilhelm I) was emerging as a hegemonic power in Europe. It had a modern, experienced army at its disposal. 1864 saw a Prussian victory in Second Schleswig War, followed by another against Austria at Sadowa on 3 July 1866. On 23 August 1866, they signed the Treaty of Prague, which saw the dissolution of the German Confederation in favour of the North German Confederation. Wilhelm I was named president of the new confederation and Otto von Bismarck its chancellor. Following its defeat in the war against Prussia, Austria lost its status as the dominant power in German-speaking lands and formed the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to be ruled by the House of Habsburg. The path was cleared for Prussia’s vision of German unification. The southern German states still had reservations about this vision, but their economic and military ties to the north played into Prussia’s hands.

Meanwhile, the French Empire was experiencing constitutional and institutional renewal. The Republican opposition to the imperial regime was strengthened in the legislative elections of May 1869, although it was ultimately defeated by the Bonapartists. Napoleon III – who had lost the support of the working-class electorate – decided to change the organs of power by the sénatus-consulte(A feature of law during the First and Second French Empires – an act with the force of law decided on by the Sénat) of 8 September 1869. The legislative body was given the right to initiate laws as well as the right of interpellation, while the Senate became a real legislative chamber. This sénatus-consulte also introduced the responsibility of the government to the Emperor. As well as these political problems, the regime also had military concerns. In 1859, France had barely scraped a victory against the Austrian Empire in Northern Italy (the piedmontese allied to Prussia at the time) and had been humiliated by the Mexican fiasco of 1867. The French Emperor was concerned about Prussia’s increase in power and sought to reform his army, which had become a shadow of its former self.

The candidacy of the Hohenzollern prince for the Spanish throne

Despite its significant financial difficulties, France was determined to stop Prussia’s rise to power. Tension between the two states was exacerbated by the proposed candidacy of Leopold, Prince of Hohenzollern (1835-1905) – a relative of King Wilhelm I – for the Spanish throne. The Spanish government offered him the crown after the abdication of Isabella II in 1868. Bismarck was in favour of this appointment, but Napoleon III, since he could not accept the prospect of a Hohenzollern on both his southern and eastern borders, was unfavourable to the prince’s candidacy, as was Wilhelm I, who did not wish at that time to poison Franco-Prussian relations.

Despite Leopold’s public renunciation of the Spanish throne, neither Bismarck nor Napoleon III could leave the matter. The former sought to provoke France into war, as he was convinced of Prussia’s military superiority and believed that the confrontation was necessary in order to facilitate German unification. The French Emperor remained convinced that the House of Hohenzollern was still determined to assume the Spanish crown.

On 2 July 1870, Bismarck made a public declaration in which he announced the renewed candidacy of Prince Leopold. This caused outcry in France and was quickly seized upon by the press. Émile Ollivier’s government could not afford to wait long to respond, and Agénor de Gramont, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, came out with a warmongering speech, which was almost unanimously supported by the press. On 9 July, the French ambassador to Prussia – Vincent Benedetti – was sent to Ems by Gramont to seek an audience with King Wilhelm. He requested a guarantee from the King that the prince would never again seek to claim the Spanish throne. Wilhelm politely refused to commit himself.

The Ems Dispatch

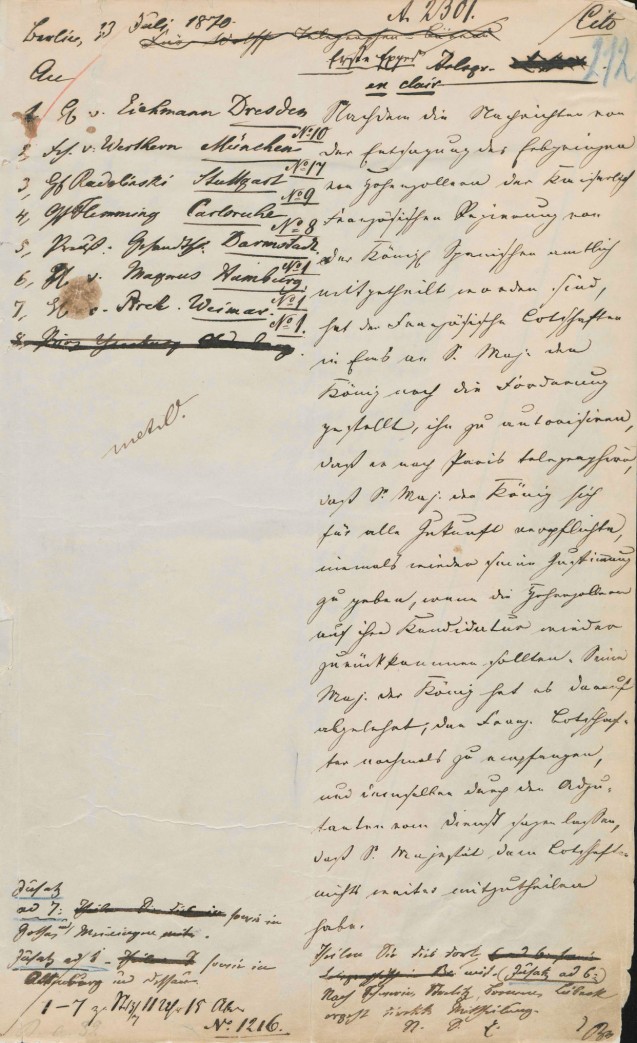

History was about the take a dramatic turn. The evening of his encounter with Benedetti, Wilhelm sent a telegram to Bismarck through Heinrich Abeken (a Prussian politician and close confidant of the king and Bismarck) to report the new demands made by the French. Bismarck seized the opportunity to ‘wave a red rag in front of the Gallic bull’ and to push France into making a mistake that would have dire consequences. He edited the telegram, taking liberties to make it more provocative, and published it the German newspapers as the ‘Ems Dispatch’. His alterations made it seem as if the Prussian king and the French ambassador had insulted one another. His last masterstroke was his use of a mistranslation to stir up further animosity: the dispatch specified that the king would no longer receive the ambassador, and instead sent an subaltern ‘adjutant’ to inform him of Prince Leopold’s decision to renounce his candidacy.

Bismarck was deliberate in his use of the word ‘adjutant’, which in the German army corresponded to a staff officer, but translated into French as an aide de camp [ADC], which is a non-commissioned rank. French pride was damaged to its very core, resulting in numerous nationalist publications and demonstrations. Nationalism also reared its head in Prussia, where the population responded in kind to the increasingly bellicose attitude of French public opinion. The situation deteriorated rapidly: the reservists were called up, and the Prussian embassy was attacked by protestors. The French Council of Ministers was hesitant to go any further, and even though King Wilhelm had renounced any aspirations to control the Spanish throne, neither the French nor Prussian press ceased with their pro-war publications, and the two states continued their march to war: a war that now seemed inevitable.

The declaration of war, 19 July 1870

Despite the fierce opposition of certain deputies (led by Adolphe Thiers), who argued that the French army was not ready to enter into direct conflict with Prussia and its allies, the mobilisation was signed on 14 July 1870. The next day, a majority of deputies voted for war appropriations. On 19 July, they declared war. When the news broke out, the people of Paris spontaneously congregated in front of the Tuileries Palace. According to the French Minister of War, Edmond Le Bœuf, the French army was ‘prête, archi-prête‘ [loaded, locked and loaded] for war. Meanwhile the armies of the Prussians and their allies, in numbers twice as strong as the French, marched along the left bank of the Rhine, ready to bury the Second French Empire in a tomb on the eastern plains.

Eymeric Job, July 2019 (translation JR)

Sources :

Bismarck, Briefe, Reden, Erinnerungen, Berichte und Anekdoten, W. Langewiesche-Brandt, Ebenhausen bei München, 1915

Der deutsch-französische Krieg 1870/71. Vorgeschichte-Verlauf-Folgen, J. Ganschow, O. Haselhorst, M. Ohnezeit, Ares-Verlag, 1909

Napoléon III, un Saint-Simon à cheval, E. Anceau, Tallandier, 2008

Napoléon III, P. Milza, Perrin, 2006