The melody and the words are thought to have been written by the British Catholic, John Wade (d. 1786), circa 1750, but in continental Europe, in Douai, the city to which Wade had fled after the failure of Bonny Prince Charlie’s ‘45 Rebellion in Scotland. The solo-line melody (written using plainsong notation) and Latin words were printed possibly in 1751.

The late-eighteenth century British composer, Samuel Webbe (a friend of Wade’s), published the hymn in London (1782) in a harmonised version in An Essay or Instruction for learning the Church Plain Chant.

Almost simultaneously in London, this piece was referred to as the “Portuguese Hymn” because it had been heard at the chapel of the Portuguese Embassy there in the 1780s. As for the French version (“Peuple fidèle”), this was written in 1790 by the refractory priest Jean-François Borderies, either in Antwerp or London.

But why is all this of any relevance to Napoleon enthusiasts?

Well, unbeknownst to most, the “Portuguese Hymn” was in fact standard funeral repertoire for British and American military bands in the first half of the nineteenth century – indeed it was played at the Duke of Wellington’s funeral in 1852. Whilst it may seem odd that such a jolly tune should be put to funereal use, the musical taste of the people of the past is frequently mysterious to those who come after! The British soldier Francis J. Bellew, recounting his military service in India in the 1820s, referred to “the solemn strains of the Adeste Fideles or Portuguese Hymn, a dirge-like air, admirably adapted for such occasions, and which breathes the very soul of melancholy.”(“Memoirs of a Griffin”, in The Asiatic Journal or Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australasia, vol. xxxviii New Series, May-August, 1842, p. 215.)

A contemporary St-Helena account of the exhumation of Napoleon’s body (1840) reports Napoleon’s second funeral procession as follows:

“At about a quarter to 4 o’clock, P.M. a Gun fired at the Alarm House, intimated that the Procession was leaving the TOMB, on its way to Town. […] About 5 P.M. the Procession reached Town […] The Town presented a very striking appearance at this moment. The English Ensigns flying at Ladder Hill and James’ Town, as well as the national flags at the foreign Consulates were floating half mast high; […] Suddenly, strains of Solemn Music came floating along the air, and the Procession was seen slowly entering the town […] [the] Band of the St. Helena Local Militia, playing a Dead March, (The Portuguese Hymn) […].(NARRATIVE OF PROCEEDINGS CONNECTED WITH THE EXHUMATION AND REMOVAL OF THE REMAINS OF THE LATE EMPEROR NAPOLEON / BY A RESIDENT printed for the proprietor by William Bateman. St. Helena – 1840, page 17-18 )

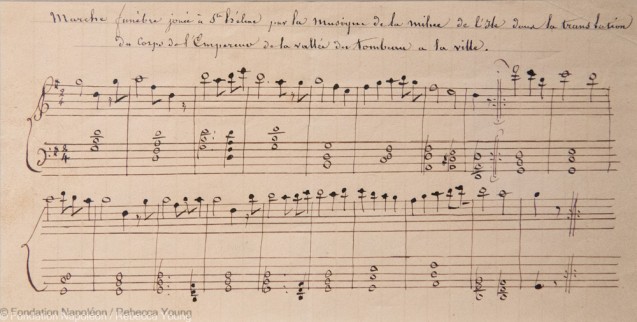

This hand-written score of an arrangement of that piece, was among the souvenirs that Napoleon’s valet Louis Marchand brought back from the expedition sent to St Helena in 1840 to repatriate Napoleon’s mortal remains to France (known as the “Retour des Cendres”).

In Paris, two months later, Mozart’s Requiem accompanied the Emperor to his final resting place, beneath the Dome of Les Invalides.

Happy Napoleonic Christmas!

Peter Hicks, December 2021

Listen to this arrangement of the “Portuguese Hymn” played on the piano by Peter Hicks and see some images of the “Retour des Cendres”.