-

Bonaparte at Arcole

Artist(s) : GROS Antoine-Jean (Baron)General Bonaparte on the bridge at Arcole, 17 November, 1796

Versailles, Musée National du ChâteauThe first emblematic image of the Napoleonic myth, this painting exalts the virtues of the military leader, as embodied by the young General Bonaparte at the head of the Armée d’Italie. In reality, Arcole bridge was not crossed. But that is not important. Here the artist glorifies the episode and makes it part of the legend. Drive, courage, overpowering will pour out of this edgy yet passionate picture. Gros had in fact been present at the Battle of Arcole, and thanks to the intervention of Josephine, he managed to get Bonaparte in Milan to sit for him several times. What Gros highlights is the image of Bonaparte as the providential saviour, the conquering hero who leads his troops, sabre in hand, seizing victory through his bravery alone.

-

Bonaparte visiting the plague victims of Jaffa

Artist(s) : GROS Antoine-Jean (Baron)Bonaparte visiting the plague victims of Jaffa, 11 March, 1799

Paris, Musée du LouvreThis masterpiece, a precursor of Romanticism, was commissioned by Napoléon in an attempt to quash rumours that he had poisoned French troops suffering from the plague during the Syrian campaign. Painted and exhibited in 1804, coinciding exactly with the creation of the Empire, this propaganda work takes on another dimension. By touching the plague victims with complete disregard for the disease, Bonaparte sets himself alongside the kings who wrought miracles, whose touch could heal scrofula, who interceded between god and mankind. This evocation of divine power in a scene in the Holy Land perfectly expresses the dynasty’s desires for legitimacy.

-

The Brumaire coup d’etat

Artist(s) : BOUCHOT FrançoisGeneral Bonaparte at the Conseil des Cinq-Cents at Saint-Cloud, 10 November, 1799

Versailles, Musée National du ChâteauThis, the best-known representation of the coup d’etat, was a commission by king Louis-Philippe for the Musée Historique de Versailles, an institution founded in 1837 with the aim of fostering national reconciliation. The painting shows the critical moment when Bonaparte, shouted down by the Conseil des Cinq-Cents, jostled and threatened, is finally forced out of the audience chamber by some grenadiers. A military intervention thus became necessary in order to begin the parliamentary coup d’etat.

That the work was exhibited at the Salon of 1840, the year of the ‘Retour des Cendres’ (when Napoleon’s corpse was repatriated from Saint Helena to Paris), gives evidence for the resurgence of the Napoleonic legend during the July Monarchy.

-

Bonaparte on Grand-Saint-Bernard pass

Artist(s) : DAVID Jacques-LouisThe First Consul crossing the Alps at the Grand-Saint-Bernard pass

Musée National du Château de MalmaisonWithout a doubt the most famous painting of the Napoleonic legend. David here exalts what was in fact quite a prosaic reality, namely that Napoleon crossed the pass riding a donkey, wearing not a magnificent cloak but a simple grey greatcoat ! The complete personification of the Romantic hero, the First Consul triumphs on a rearing charger in a diagonal composition, the very image of irresistible rise. A propaganda masterpiece, the work puts Napoleon on a par with the conquerors of antiquity, namely Hannibal and Charlemagne, whose names appear graven in the foreground rocks.

Four variants of the original painting commissioned by Charles IV of Spain exist. They were painted by David and his workshop and differ in the colour of the horses and the cloak.This painting was shown as part of the exhibition Napoléon et l’Europe at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris, from 27 March 2013 to 14 July 2013.

-

The sacre or coronation

Artist(s) : DAVID Jacques-LouisThe sacre or coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I

Paris, Musée du LouvreCommissioned by Napoleon I for the Salle des Gardes of the Tuileries Palace. Exhibited at the Salon of 1808.

An ambitious composition representing the coronation, which took place on 2 December, 1804, in Notre-Dame cathedral, this canvas took three years of detailed work to complete. David, who had in 1804 received the title of “Premier Peintre de l’Empereur”, created a monumental group portrait in which everything conspires to push the viewer’s attention towards the central scene. It is in fact the coronation of Josephine, not that of Napoleon, which is the subject of the painting. The harmony of the composition is remarkable, with the figures set either side of the large central gold cross. The huge size of the work (six metres tall by ten metres wide) made it possible to indulge in the remarkable luxury of painting identifying features for each character – even for Madame Mère, who though absent from the ceremony nevertheless dominates the foreground of tribune! In expressing his satisfaction for the painting, Napoleon is said to have remarked: “This is not painting; you walk in this work”.

Here in this picture can be seen portraits of Pius VII, Charles Le Brun, the Duc de Cambacérès, Berthier, Eugène de Beauharnais, Caulaincourt, Bernadotte, Cardinal Fesch, Comte Estève, Comte d’Harville, Murat, Sérurier, Moncey, Bessières, Ségur, Belloy, Mme de la Rochefoucauld, Mme de la Valette, Julie Clary, Hortense de Beauharnais, Elisa, Pauline and Caroline Bonaparte, Louis and Joseph Bonaparte, Kellermann, Lefebvre, Pérignon, Duroc, Rémusat, Junot, Laetitia Bonaparte (in fact absent from the ceremony), Caroline Fontanges, Cossé-Brissac, Lacépède, Soult, Beaumont, and Gravina and Armstrong John.

Have a look at a sketch for this work from the Collection of the Fondation Napoléon.

-

The Emperor as Legislator

Artist(s) : DAVID Jacques-LouisNapoleon in his study in the Tuileries Palace

Washington, National Gallery of ArtTotally unlike traditional portraits of sovereigns in their robes of state, this standing portrait is a realist allegory of the emperor’s civilian activities. Napoleon is wearing the blue uniform (with white lapels) of a Colonel of the Grenadiers à pied de la Garde, normally worn on Sundays, the green Chasseurs à cheval uniform being for daily use. He is in the trademark stance, his right hand is thrust inside his waistcoat. The candles are burned down, the clock shows four in the morning, his pen and paper are thrown down on the desk, everything is designed to imply that he has just spent all night working on the Code Civil. Dawn is rising and the emperor is preparing to go and review his troops. The picture’s message is clear: the military leader is also a powerful statesman, administrator and legislator, whose capacity for work is unparalleled.

-

The Battle of Austerlitz

Artist(s) : GERARD FrançoisBattle of Austerlitz, 2 December, 1805

Versailles, Musée National du ChâteauCommissioned to commemorate the Grande Armée’s most famous exploit and exhibited at the Salon of 1810, this gigantic canvas was originally destined for the ceiling of the chamber in which the Conseil d’Etat met. The subject is the solemn moment of victory, with General Rapp presenting to an Olympian Napoleon the standards taken from the enemy. The composition, although broad and balanced, is nonetheless complicated (indeed almost too much so), and in it Gérard reveals himself to be at the limits of his ability as a history painter. That being said, the ‘Sun of Austerlitz’ almost supernaturally fills the scene, perfectly matching the symbolic character of the date, ‘2 December’, within the Napoleonic legend.

-

The Battle of Eylau

Artist(s) : GROS Antoine-Jean (Baron)Napoleon visiting the battlefield of Eylau, 9 February, 1807

Paris, Musée du LouvreEylau was made the subject of a competition in March 1807, less than a month after the terrible battle which resulted in more than 50,000 French and Russian victims. Whilst underlining the French victory, the principal purpose of the winning picture was to express Napoleon’s emotions in the face of such carnage. “If all the kings of the earth could view such a spectacle, they would be less keen on wars and conquest”, the emperor is said to have declared. Gros, the winner of the competition, here in this picture reached the summit of his art, elevating history painting to a level never equalled, before or since. Under a leaden sky, his face washed out but marked with immense pity, Napoleon crosses the battlefield dotted with corpses. Set against the dark silhouette of Murat, the personification of the pitiless warrior, the emperor is the embodiment of humanity and compassion. Here for the first time victory’s dark side, the other side of the coin, is painted in all its cruel reality.

-

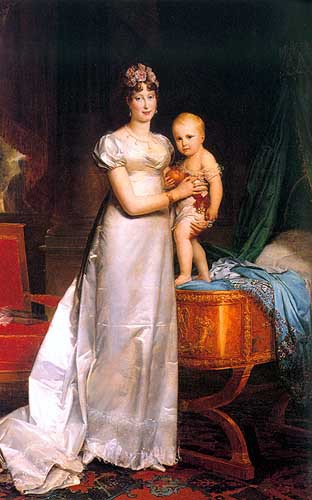

The Empress and the Roi de Rome

Artist(s) : GERARD FrançoisMarie-Louise, Empress of the French, and the Roi de Rome

Versailles, Musée National du Château

Known to his contemporaries as «the painter of kings and the king of painters’, Gérard was the official portrait painter of Napoleon, the imperial family and the grand dignitaries of the First Empire. This specialisation won him honours in abundance. Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur in 1802, ‘Premier Peintre’ for the Empress Josephine in 1806, Professor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1811, Member of the Institut in 1812, he also led a brilliant career after the fall of the Empire when he became ‘Premier Peintre’ for Louis XVIII in 1817. Placing himself within the tradition of the great court portrait painters, Gérard painted official portraits which, particularly in his female portraits, were frequently ‘softened’ or deformalised. Indeed, the grace of his draughtsmanship, the richness of the colours, and the background, clearly evocative of the social status of the sitter, all conspire to give a sense of intimacy, bringing the viewer closer.

-

The Retreat from Russia

Artist(s) : CHARLET Nicolas-ToussaintAn episode from the retreat from Russia, 1812

Lyon, Musée des Beaux-ArtsIt was the Romantic generation, the ‘children of their time’, brought up on nostalgia for the Napoleonic epic, who took to painting the disaster of the retreat from Russia. Charlet, a pupil of Gros’s and best known for his lithographs, presented this poignant and intensely dramatic canvas at the Salon of 1836. Here we are shown the remains of the Grande Armée, directionless, anonymous soldiers, gradually sinking beneath a snow storm. Musset, astounded by the picture, wrote: “This is man in his wretchedness, alone under a darkening sky, earth frozen solid, without a guide, without a leader, completely faceless – this is despair in the desert”.

-

The Campagne de France

Artist(s) : MEISSONIER ErnestThe Campagne de France, 1814

Paris, Musée d’OrsayWhilst a fruitful source of inspiration for the Romantics, the Napoleonic epic was no less influential upon Academic painters. Meissonier’s work, one of the artistic highlights of the Second Empire and the Third Republic, is ample witness. Though born only a few months before Waterloo, Meissonier was greatly interested by Napoleon (“How many times I have dreamt of the emperor!” he was heard to remark) and he sketched out a plan for a ‘Napoleonic cycle’ comprising five major dates: “1796”, “1807”, “1810”, “1814” and “1815”. Only “1807” and “1814” were ever finished – although he did complete two other paintings related to the cycle, namely, “1805” and “1806”. Meissonier perfectly summed up the painting here in the following words: “The Campagne de France. Heavy sky, ground churned up, staff battered, army exhausted. The emperor goes ever onwards, mounted on his white horse. It is not so much the defeat of the armies but the attitude of Napoleon I in this critical time which is important”.

-

The death of Napoleon

Artist(s) : VERNET HoraceNapoleon on his deathbed

Private collectionIn his youth, Horace Vernet was soaked in the Napoleonic epic and its dreams of glory, and following in the family tradition he very soon chose a career as a history painter. During the Restoration, his studio was a haven for those nostalgic for the emperor, and he too revealed his own fervent admiration for Napoleon in his paintings, which themselves in fact contributed to the propagation of the legend. This small picture, moving in its simplicity, concentrates on the dead Emperor’s face. The laurel wreath is the only obvious sign that this is not so much posthumous homage but rather a painting of glorification.

K.H. tr. P.H.

For further information on these works, consult the versions which appear in the ‘In pictures’ section.

Crédits : RMN, CGFA, The Artchive, Fondation Napoléon.

- Bonaparte at Arcole

- Bonaparte visiting the plague victims of Jaffa

- The Brumaire coup d’etat

- Bonaparte on Grand-Saint-Bernard pass

- The sacre or coronation

- The Emperor as Legislator

- The Battle of Austerlitz

- The Battle of Eylau

- The Empress and the Roi de Rome

- The Retreat from Russia

- The Campagne de France

- The death of Napoleon