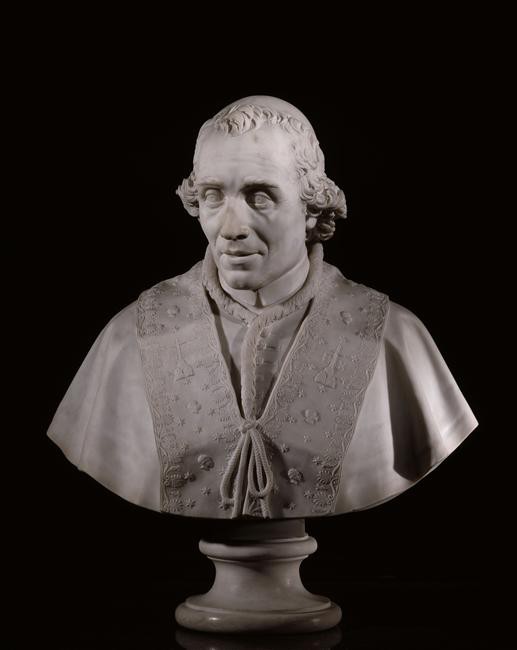

This bust of the Pope who consecrated Napoleon I, made by Antonio Canova, is held at the Château de Versailles. The marble likeness echoes the Pope’s brief visit to Louis XIV’s château, on 3 January 1805 (see here an account of the Pope’s visit to Versailles). Pius VII had been invited to Paris by Napoleon to take part in the consecration and coronation of the Emperor in Notre-Dame, which took place on 2 December 1804.

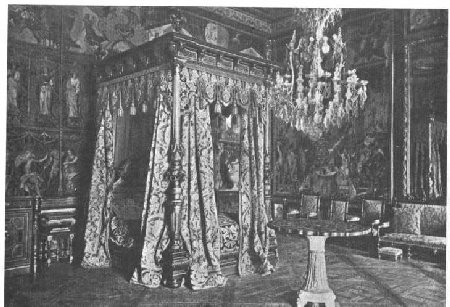

At the end of his journey to the French capital, the Pope was to stay three days in another imposing royal château, namely the Château de Fontainebleau, (25 to 28 November 1804), thereby forshadowing his much longer stay when Pius was to be the Emperor’s captive, from June 1812 to January 1814.

Relations between the Pope and the First Consul and later Emperor were never straightforward. And as Napoleon’s imperial power extended, so Napoleon came increasingly to see Pius VII as an obstacle. Throughout the reign of the Emperor of the French, Pius tried to preserve his temporal power and the neutrality of the Papal States, missions for which this moderate Pope was not at the outset the ideal candidate.

A Moderate amidst Republicans and Counter-Revolutionaries

Pius VII was born Barnabé Chiaramonti in Cesena, in the Papal States, on 14 August 1742. Aged 16, he became a Benedictine and, in 1766, professor of theology in Parma and then Rome, with the support of Pope Pius VI, also from Cesena. He was renowned for his penetrating, indeed occasionally mocking, intellect and revealed Jansenist tendencies. He was thus a supporter of Church reform, moving her away from foreign policy to personal spirituality, whilst at the same time avoiding too rigid a dogmatic position.

Appointed Bishop of Tivoli in 1783, again under Pius VI’s good agency, he became Cardinal two years later. His moderate, thoughtful position made him equally popular with both the laity and the church hierarchy. He created consensus around him. That being said, events were to force him to face up to the political issues of his day.

In Imola, where he was performing his new episcopal role, he was brought suddenly face-to-face with the Revolution: in 1796, troops under General Augereau occupied his diocese. Unlike other Italian Bishops of his time, Barnabé did not flee the town but called upon the people to react calmly. His moderate position did him however a disservice with both opposing camps: neither the French Revolutionaries nor Counter-Revolutionaries had any confidence in him.

Imola became part of the first Cisalpine Republic in February 1797, as per the Treaty of Tolentino. The Cardinal-Bishop then set aside his coat of arms and the baldachino over his throne in an attempt at appeasement. He expounded his understanding of cohabitation with the Republic in his sermon for Christmas 1797, in which he proposed submission to the new republic founded a few weeks earlier and offered a conceptual model for Catholic faith within a virtuous and balanced democracy.

This position was not just a minority one within the Curia but also one that was viewed with great suspicion by the French Revolution given that Catholic authorities in general were suspected of collaborating with Counter-Revolutionary attacks. When the Directory ordered the occupation of Rome in January 1798 and sent Pius VI into captivity in Valence, Chiaramonti’s centre-ground policy became difficult both for the laity and the Catholic hierarchy. After the death of Pius VI, on 29 August 1799, he was nevertheless to be elected Pope by the conclave that met in Venice (Rome being occupied) after long deliberations.

In the Vatican, a spiritual bulwark but politically weak faced with Napoleonic expansionism

The Conclave made this hesitant choice because they hoped that Pius VII’s experience of playing for time in Imola would speak to Republicans, whilst at the same time hoping that the Holy See could remain to a certain extent independent.

No longer Cardinal but now Pope, thus representing the whole Church, Pius took on the mantle of bulwark and stiffened his resistance to the Directory, in particular after the Peace of Lunéville which had enshrined the loss of the richest provincial territories in the Papal States.

He was also subject to other European power sensitivities. Since he had been elected in opposition to the papal candidate supported by Austria, on Emperor Francis I’s request, Pius was crowned with little pomp, and the new Pope refused the invitation to come to Vienna in protest. Such isolation rendered his job much harder. Indeed without firm support from other members of the coalition against Napoleon, the territories in his temporal power were drowned in a sea of Napoleonic conquests.

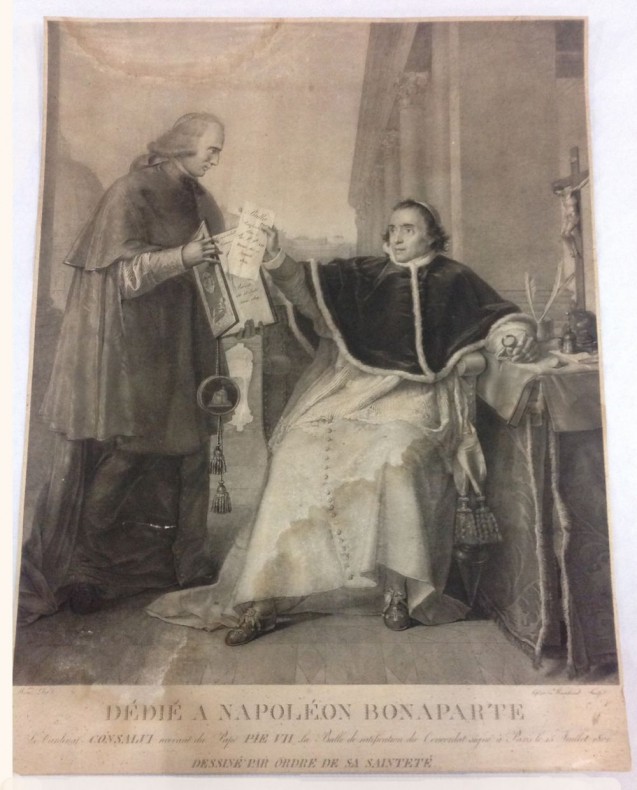

Even though on the defensive in terms of foreign policy, Pius VII in 1803 managed to persuade the First Consul to allow the re-establishment of the Papal States. It was with this in mind that he negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with the First Consul Bonaparte, and then the Italian Concordat of 1803, the political concessions made to the French government being counterbalanced by the official return of the Catholic church to France, a Church that had all but disappeared during the Revolution. The Italian Concordat, on the other hand, was more flexible and allowed the stabilisation of the Church in Italy. Since his room for manouevre was so slight in the diplomatic and geographical domains, Pius VII decided to limit his intransigeance to the spiritual sphere.

In parallel with his intellectual primacy over the Catholic communion, Pius VII noted also the changes implied by the Enlightenment and revolutionary aspirations. He fiercely defended the idea of modernising the Church from within, occasionally against the advice of the Curia. This attempt at reform, written with the help of his secretary Consalvi, enshrined in the bull “Post diuturnas” dated 30 October 1800, was only to be partially enacted.

His positivist views, before the letter, and his preference for persuasion via reasoned dialogue were quickly to come up short when faced with Napoleon I. Pius had come to Napoleon’s consecration in 1804 hoping to modify certain parts of the Concordat and notably to bring about the abrogation of the Organic Articles attached to the 1801 Concordat. To no avail.

Their relations steadily worsened as Napoleon conquered ever more of Europe, especially in Italy, starting with the victory at Austerlitz. Pius VII did not manage to get Napoleon to accept his policy of neutrality, notably with respect to the Continental Blockade against Britain, demanded by the French Emperor.

Their drifting apart occured gradually: Pius VII, on the one hand, refused to grant Jérôme Bonaparte’s divorce (1805) and refused to recognise Joseph Bonaparte as King of Naples (1806), whilst Napoleon, on the other, nibbled away at the Papal States (1806 to 1808), to which the Pope replied by refusing to invest bishops.

When Napoleon finally annexed the Papal States to the Empire on 17 May 1809, Pius VII replied with a bull of excommunication of all those who “usurp, encourage, advise or perform” violation of, the temporal sovereignty of the Holy See, published during the night 10-11 June 1809 and aimed, by implication but not nominally, at Napoleon.

Once the Pope had been kidnapped by General Radet less than a month later (night of 5-6 july) and transferred first to Savona (until 1812) then the Château de Fontainebleau (until 1814), there began a intellectual and political battle of wills between Pius VII and Napoleon. The former was at the mercy of the latter, but the Pope under house arrest knew how play the long game, appearing to cede and then coming back strong again, and also opposing Napoleon head-on with the support of those cardinals in France who had remained loyal to him.

As the Emperor gradually began to lose ground in Europe, Pius VII – often subject to severe doubts – began to take heart. His passive resistance had paid off, and he was returned by Napoleon to his States in January 1814. Napoleon on the other hand was to have to face the Campaign of 1814 and the invasion of France’s pre-Revolutionary frontiers.

The end result was that the Pope who had been most conciliatory to the ideas of the French Revolution and the least interested in political and temporal matters became in fact one of Napoleon’s stubbornest opponents, despite the lack of any military might (for more on their relations, see Napoleon and the Pope: From the Concordat to the Excommunication).

Pius VII in the end bore no ill will and – partly under the encouragement Cardinal Fesch – provided sanctuary for members of the Bonaparte family (Madame Mère and most of Napoleon’s brothers and sisters were to benefit from the Pope’s protection and help) and in 1817 was even to request a leniency for Napoleon on St Helena.

Pius VII’s heritage

Pius VII was not simply the quiet opponent of Napoleon as portrayed in collective memory. Though driven into action on serious political issues which his natural leanings would have pushed him to avoid, he was just as vigorous in his theological action. He was the origin of the canonisation of the founder of the Ursulines, Angèle de Merici, in 1807, of the beatification of the founder of the Redemptorists, Alphonse de Liguori in 1816, and he re-established the Jesuits in 1814. During his Pontificate, Copernicus’s theories were validated by the Church (1822).

His desire to stabilise Catholicism in Europe nevertheless pushed him occasionally towards anti-Revolutionary actions, such as: the return of the ghettos for Jews in 1815; and the condemnation of Free Masonry in 1821, … That being said, he was to fight against slavery throughout his Papacy.

He was extremely cultivated and after his death, on 20 August 1823, he left behind him a Chiaromonti Museum begun in 1807, which included many pieces from archeological excavations in Ostia, the antique port of Rome, and other pieces recuperated after the requisitions made during the occupation by the French Empire.

Indeed, it was to the sculptor Antonio Canova, who immortalised Pius in this bust in circa 1806, that Pius VII was to turn for the recuperation of these pieces, in majority from the Museo Pio-Clementino, and for the creation of the museum that bears his name and which still today makes up a large part of the Vatican Museums.

Marie de Bruchard

May 2019, trans. P.H.

From the entry in the Dictionnaire Napoléon (Fayard, 1999) by Jean-Marcel Champion.

More:

- Le Pape et l’Empereur. La réception de Pie VII par Napoléon a Fontainebleau. 25-28 novembre 1804 (Somogy Éditions d’art, Château de Fontainebleau, 2004)

- Pie VII face à Napoléon. La tiare dans les serres de l’Aigle (éd. du musée de Fontainebleau/Rmn, publié avec le concours de la Fondation Napoléon, 2015), catalogue of the eponymous exhibition which was held in the Château de Fontainebleau in 2015.

These two books can be read at the Bibliothèque Martial-Lapeyre, at the Fondation Napoléon.