In 1861, to many people’s astonishment, the young architect Charles Garnier (1825-1898) won the competition to design a new opera house in Paris. The project was launched by Napoleon III a short while after Orsini’s attack of 14 January 1858, when the latter had attempted to assassinate the Imperial Couple as they arrived for a performance at the Opera on Rue Pelletier.

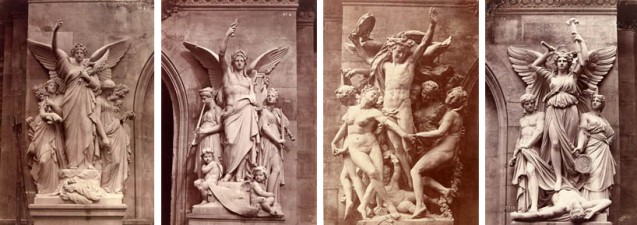

In this enormous project Garnier employed four sculptors each to create a group of figures to adorn the façade of the new Opera. François Jouffroy (1806-1882) was given the theme of ‘Harmony’ (lyrical poetry), Eugène Guillaume (1822-1905) that of ‘Instrumental Music’, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875) was given the theme of ‘Dance’, and Joseph Perraud (1819-1876) was given that of ‘Lyrical Drama.’

The sculptures were revealed to the public over two separate days; the first two themes on Saturday 24 July 1869, and the other two the following day (Le Rappel, 25 July 1869). The Parisians who gathered en masse in front of the Opera on the Sunday had no idea of the scandal that would unfold, caused by the brazen design of one of the sculptors.

Comparison of the four groups of figures (photographs by Durandelle and Demaet for Charles Garnier) shows at first glance how much Carpeaux’s work stands out from the others:

Photos by Durandelle and Demaet, in “Le Nouvel Opéra de Paris”, for Ch. Garnier 1875-1876, vol. Sculptures

© BnF – Gallica

And the stone began to dance…

The first official commission of 17 August 1865, signed by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Philibert Vaillant (1790-1872), Minister of Fine Arts (from 1863 to 1870), was clear: ‘Monsieur Carpeaux is tasked with sculpting one of the groups of figures that will decorate the base of the façade of the New Opera. These groups, comprising three figures with their relevant accessories, will be 2.60m high and will be made from Échaillon marble; a sum of three thousand francs is allocated for this work.’ In his excitement, Carpeaux first imagined a group of no fewer than 17 figures. But as his design was to adorn the façade of a structure that was already certainly going to upset the balance of Parisian architecture (albeit it in quite a controlled manner) and had to fit in with the design and scale of the building, Carpeaux reigned in his horses and dramatically reduced the number of figures to 9.

The sculpture group composition centred on the spirit of the Dance, brandishing a tambourine. The androgyny derived from the incorporation of the feminine traits of Carpeaux’s first project – a sculpture of Helene Van Donning, Princess Racovitza – and the male body of the carpenter Sébastien Visat, who worked for Carpeaux.

The spirit is surrounded by naked dancers, tumbling in a wild ring, while cupid lies its feet, balancing out the lower part of the sculpture. The general impression is one of vivacity, gaiety, and indeed unbridled sensuality. The liberated bodies of the female dancers (the ‘immodest circus ladies’ (cascadeuses) according to Le Figaro on 2 August 1869) and their apparently fevered faces remove all sense of academism from their nudity.

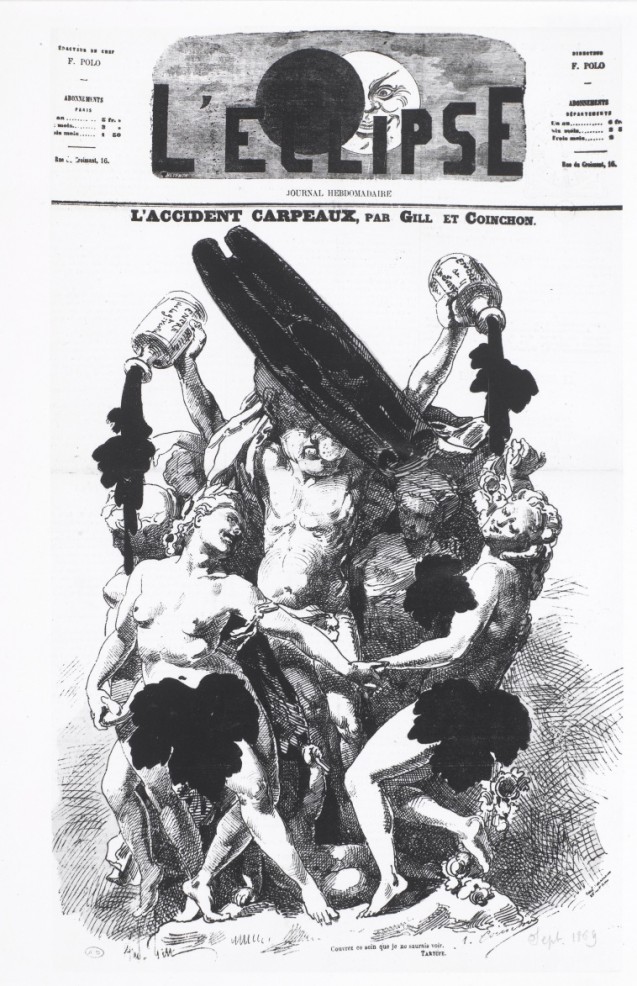

Ink attack

Considered indecent, obscene, and immoral (the dancers were described as ‘drunk mænads’ in Le Siècle journal of 13 August 1869), Carpeaux’s work was defaced with black ink a month later, during the night of 26 and 27 August. Was this the act of a devout catholic? Or was the attack carried out by one of Carpeaux’s rivals? Interrogations ensued, and on 31 August, La Presse almost went as far as to accuse Carpeaux himself, suggesting that he may have defaced his own sculpture so that it would be better protected in the future.

Front Page of “L’Eclipse” 11 September 1869

© RMN GP, Musée d’Orsay / Patrice Schm

There was talk of removing Carpeaux’s sculpture from the façade and replacing it with a new work, commissioned from Charles Gumery (1827-1871). The latter’s death, along with the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) interrupted the process, and Carpeaux’s original sculpture remained in place until 1964, when it was removed to the Louvre (the Musée d’Orsay became its final resting place in 1986) for protection and replaced by a copy by the sculptor and medallist Paul Belmondo (1898-1982). Gumery’s sculpture was completed the year after his death and has been preserved at the Musée d’Angers since 1885.

Carpeaux, an artist ‘qui faisait plus vivant que la vie’ [whose works were more lifelike than those created by life itself] (Alexandre Dumas fils)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux was born in Valenciennes on 11 May 1827 into a family of modest means (his father was a bricklayer and his mother was a lace maker), and his family moved to Paris in 1838. In 1842 he began his artistic training at the Petite École, a royal school of drawing and mathematics directed by Jean-Hilaire Belloc, who was a friend of the painter Jean-Dominique-Auguste Ingres. It was here that he first met Charles Garnier. On becoming responsible for his family after his father left for the United States, Carpeaux was forced to work for porcelain makers and bronze smiths. He also received assistance from two charitable bodies, the Société des Enfants du Nord and the Société du Département du Nord.

From 1844 to 1854, he trained in the ateliers of Abel de Pujol, Rude, and Duret. In September 1854, he was the recipient of Grand Prix de Rome for his work Hector implorant les Dieux en faveur de son fils Astyanax [Hector imploring the Gods on behalf of his son Astyanax]. However, on receiving an official commission to contribute to the decoration of the Louvre, he did not join the Académie de France in Rome until 1856. He stayed until 1862, but had a difficult time due to health issues and to his unwillingness to bow to the constraints of the Académie. During this period at the Académie his most significant works were Jeune pêcheur à la coquille [Neapolitan fisherboy with shell] (1858), Ugolin (1858-1861: his final year piece, inspired by Canto XXXIII of Dante’s Inferno) and a fountain that paid hommage to the painter Watteau (Valenciennes).

Upon his return to Paris in 1862, Carpeaux was introduced to the Princesse Mathilde, of whom he sculpted a bust (1862-1863). This was followed by purchases and official commissions from the Imperial Couple (he sculpted a bust of the Empress Eugénie in 1866, and a statue of the Prince Impérial and his dog Néro in 1865). In 1863, the architect Hector-Martin Lefuel (1810-1880) commissioned him to decorate the Seine façade of the Pavillon de Flore of the Tuileries: the resulting work was a bas-relief titled La France éclairant le Monde et Protégeant la Science et l’Agriculture, [France enlightening the World and protecting Science and Agriculture] which showed children carrying palms in the spandrels of the dormers.

On 29 April 1869, Carpeaux married Amélie de Montfort. She was 20 years his junior, and the daughter of the General Vicomte de Montfort. The couple would have four children: Charles (b. April 1870); Louis-Félix, born in July or August 1871 in London whence Carpeaux had fled with his pregnant wife and young son Charles; Louise-Marie (b. November 1872); Louis-Victor (b. February 1874).

In 1871 he was hired to create a bust of Napoleon III in exile, and went to the Emperor’s residence in England to make some preliminary sketches, returning to Paris in 1872. He travelled back to England several days after the Emperor’s death, (which had occurred on 9 January 1873 in Chislehurst), where he took some final sketches so that he could create a stripped back sculpture that showed the more human, suffering side of Napoleon III.

Carpeaux was not just a sculptor but also talented at painting and drawing (see his self-portrait at the MET in New York City).He was an accomplished artist on all fronts but, despite his success, had to have parts of his sculpture groups and scale versions of his busts copied and reproduced in order to commercialise them.

Terracotta, 1873

© RMN GP Musée des Beaux-Arts Valenciennes / René-Gabriel Ojéda

Carpeaux also directed a lot of his attention to the commercialisation of photos of his works. When photography burst into the art world, the question of intellectual property became an issue. In 1869, Carpeaux gave the exclusive sale rights for photos of La Danse to the photographer Appert (this included photos with or without the ink marks from the attack, as indicated by the notice in Le Rappel on 12 September 1869). Upon discovering that the photographer Jules Raudnitz (1815-1899) had also taken photos, Carpeaux and Appert attempted to sue him. But as the sculpture had been an official commission, they lost their case. The Tribunal Civil de la Seine (1ère Chambre) ruled that ‘the right to the reproduction of a work of art (in this case a sculpture) is transferred at the same moment as the rights of ownership for the work, of which it is only an accessory right, so when this transfer of ownership takes place on the part of the author, the reproduction rights are not retained’ (Le Droit, Journal des Tribunaux, 31 March 1870).

During the year 1874, Carpeaux would create a number of new works, and his fountain for the l’Observatoire in Paris was inaugurated on the 24 August. But the last two years of his life (1874 and 1875) would go on to be marred by his worsening health (he developed bladder cancer) and family problems (between his immediate and extended family). The severing of ties with his brother over the management of the atelier founded in 1872 (the contract between the sculptor and his brother, signed on on 12 April 1872, stipulated that Émile had ‘complete control over the manufacturing of all of his [Carpeaux’s] works for their production and reproduction in marble, bronze…’) caused massive financial problems for the artist. He died in Courbevoie on 12 October 1875, at the age of 48.

Irène Delage, January 2020, translated by JR and PH

► La Danse fact sheet on the Musée d’Orsay museum website

► Book referenced: Peintures et sculptures de Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Musée de Valenciennes, , 1978, 128 p.

► Photo album showing the construction of l’Opéra Garnier (on the website for the Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

► Photograph: Protection des monuments parisiens contre les raids aériens durant la guerre 1914-1918 > “La Danse” de Carpeaux, façade de l’Opéra Garnier, début février 1918 [The protection of Parisian monuments against air raids during the war of 1914-1918 – “La Danse” by Carpeaux, on the façade of l’Opéra Garnier, beginning of February 1918 (website Paris en images)

► Photo by Roger Shall (1904-1995) of American Marines posing on the sculpture ‘La Danse’ by Carpeaux in 1945, Opéra National de Paris (site Paris Musées)