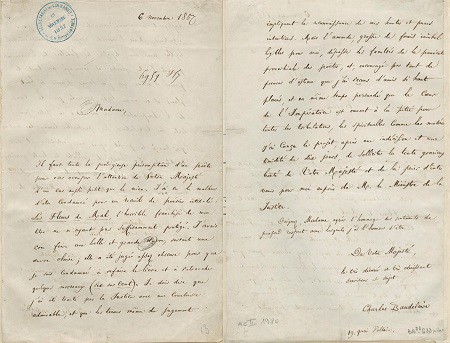

6 November 1857,

Madame,

I needed all the prodigious presumption of a poet to dare to trouble your Majesty and bring to her attention a case as petty as my own. I have had the misfortune to be condemned for a collection of poems entitled “The Flowers of evil”, whose horribly frank title was not sufficient to protect me. I thought I had written a great and fine work, above all a transparent one; it was considered sufficiently dark and impenetrable that I have been condemned to rewrite the book and remove several poems (six out of one hundred). I must say that I was treated with admirable courtesy by the Justice, and that the very terms of the judgement placed upon me implied a recognition that my intentions were noble and pure. But the fine, enlarged as it was by additional costs which to me appear quite unintelligible, is beyond the means of the proverbial poverty of poets, and, encouraged by the very many demonstrations of esteem that I have received from friends in high places, and indeed, being certain that your Imperial Majesty’s heart was open to pity for all tribulations, be they spiritual or material, I took the decision, after ten days of hesitation and timidity, to call upon your Majesty’s gracious goodness and to beg her to intervene on my behalf with the Minister of Justice.

Please accept, Madame, the expression of the most profound respect, with which I am honoured to be your Majesty’s devoted and obedient servant and subject,

Charles Baudelaire,

19, quai Voltaire[Read the original French text of this letter] [Have a look at a close-up of the letter recto-verso]

When the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) sent this letter to Empress Eugénie on 6 November, 1857, he was at a very low ebb, following the court case, on 20 August, for the offending of public morals, of public good behavior, and of religious morality. His legal misfortunes had begun shortly after the 1,100 copies of his Les Fleurs du mal went on sale on 21 June, 1857. The collection of poems was published by his friend and publisher Auguste Poulet-Malassis (1825-1878), who had been co-director with his brother of the house of Poulet-Malassis/de Broise since 1855.

Less than two weeks after publication, rumours began to fly: there were threats of seizure and Baudelaire directed his publisher: “quick, hide, carefully hide the whole print run”. On 5 July, the Figaro journalist Gustave Bourdin opened hostilities against the collection and the author: “Never before have we seen such brilliant qualities so madly squandered. […] The hateful rubs shoulders with the ignoble; the repulsive stands alongside the vile. […] This book is an asylum open to every sort of dementia”.

The critical assassination was followed by judicial procedure: the case was handed to the “6e chambre de police correctionnelle”. On behalf of the Imperial procurer, Ernest Pinard had already mounted a case – unsuccessfully – in January 1857 against Flaubert and the publication of Madame Bovary on the same grounds of offending public morals. He waged a pitched battle against Baudelaire. The poet however was assisted in the preparation of his defence by the celebrated literary critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve, a regular correspondent with Princesse Mathilde, and by the historian and writer Prosper Mérimée, who was close to the Empress. But he was to look for even more august support.

“Flaubert had the Empress on his side. I am in need of a woman”

After the seizure of the copies in mid-July, but before the judgement dated 20 August, 1857, Baudelaire sought the protection of Achille Fould, the Minister of the Imperial Household, ministry in charge of the Moniteur Universel. This government organ initially defended the poet’s right of artistic expression in the face of the Figaro’s criticisms. After all, the serialised publication of parts of Les Fleurs du mal in reviews such as L’artiste, Les poètes de l’amour, or La revue des deux mondes (beginning in 1845) had not raised any eyebrows. However, the ministers of Justice and of the Interior, Abbatucci and Billault respectively, refused any intervention on the poet’s behalf.

Though he had no access to the Imperial inner circle, Baudelaire thought he could nevertheless get higher by calling upon the woman he adored, Apollonie Sabatier, known as “la présidente”, a socialite powerful in the entourage of the Emperor’s half brother, the Duc de Morny. Baudelaire wrote to her: “Flaubert had the Empress on his side. I am in need of a woman”. The author of Madame Bovary had benefited from the intervention of the Empress and had thereby avoided condemnation.

Did Apollonie Sabatier plead Baudelaire’s cause with Morny? There is no trace of any intervention. Eugenie, however, did accede to the request presented in the letter dated 6 November: the 300 Franc fine was cut to 50. His publishers, on the other hand, were forced each to pay 100 Francs and six poems were cut from Les Fleurs du mal (thirteen had been named in the accusation).

The Empress intervenes

It is not known quite why Eugenie intervened. She could hardly have intended to protect all artists threated with censorship; and she would have been much more likely to have approved of a policy defending “good morals” than the other way around. Les Fleurs du mal were definitely not her sort of reading material. Whilst her action could be read as an act of clemency which befitted the Empress’s reputation, it was nevertheless an entirely political act. Baudelaire’s reputation as an art critic of great finesse had been established in the mid-1540s. He had also become the official translator of Edgar Allan Poe since his translation of Poe’s The Philosophy of Composition (French title, “La Philosophie de l’ameublement”) in 1854. As a result, he had become an important figure in the Parisian art world, a milieu that had suffered as a result of the exile of some of its major figures, notably Victor Hugo. The latter had written a letter of encouragement to Baudelaire from Guernesey on 30 August 1857: “You have just received one of the rare decorations which this regime can actually award”.

By choosing to reduce the fine but not to quash the judgement, the Imperial regime (via Eugenie) had confirmed Baudelaire’s guilt, officially repressing the licentiousness perceived in his verses, but nevertheless easing the life of a poet up to his eyes in debt. The fact that the reduction of the fine took place several months after the court case also reveals the Empress’s desire to wait for the matter to disappear in the press before granting the request.

That being said, the favour to Baudelaire did not stop Napoleon III from rewarding the implacable and zealous (and this time successful) procurer’s replacement. Pinard was to receive the Légion d’honneur the following year. That very conservative jurist was to participate in the writing of a law on the press and briefly to become Minister of the Interior from 1867 to 1868. As for the author of Les Fleurs du mal, he died in Paris on 31 August 1867, riddled with syphilis.

Marie de Bruchard, July 2017 (translation Rebecca Young and Peter Hicks)