The University Claude Bernard Lyon 1 (FR-CERESE) carried out a crowdfunding campaign in the spring of 2018 in order to supplement the funding that the eReCoNat programme had obtained for the digitisation of Prince Roland Bonaparte’s exceptional herbarium.

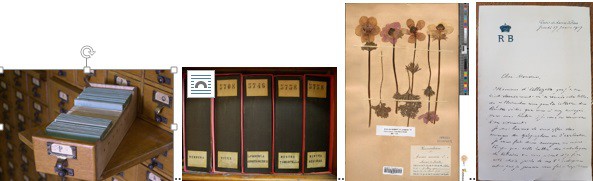

A 13m-long industrial scanning bench was installed amongst the herbarium’s antique furniture in order to digitise the dried plants at an impressive speed of 3,000 images a day! Thanks to numerous donations, including one from the Fondation Napoléon, and rallying of the public and the media, 28,000 euros were raised in two months, which was four times more than had been expected!

This money meant that the entirety of Bonaparte’s broad-based herbarium was able to be digitised, a feat which seemed impossible a year ago! 558,000 images of this herbarium are online along with 10 million other French naturalistic objects on the free database accessed through ReColNat (French or English) ReColNat is le Réseau National des Collections Naturalistes (the National Network of Naturalistic Collections). It aims to promote all French naturalist collections via a digital platform which is open to everyone. There are already more than 10 million images on the site! and each day new images are added. The target of 760,000 sheets, which would be the entirety of the Bonaparte collection, should be obtained between now and this summer.

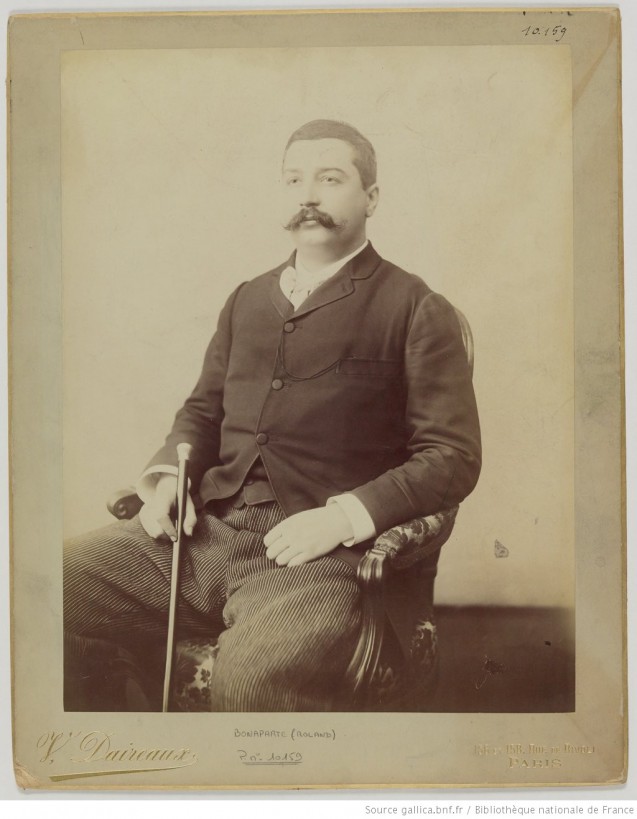

Who was Roland Bonaparte?

Amongst all the different collections preserved in the herbarium at the UCB Lyon 1, which is one of the biggest herbariums in the world and is recognised by this acronym LY, the collection of Roland Bonaparte (1858-1924) is iconic. Roland Bonaparte was the great-nephew of Napoleon I, the grandson of Lucien and the son of Justine Eléonore Ruflin and Pierre-Napoléon Bonaparte (famous for killing the journalist Victor Noir, in 1870, in a duel). Roland’s father’s numerous escapades led to Roland spending his infancy isolated from the rest of the Bonaparte family. Despite this, he graduated from Saint-Cyr in 1879 and began a military career as a sub-lieutenant of the line infantry, a career which was stunted when a law was introduced in 1886 which forbade members of the families which had ruled over France from serving in the army.

In 1880, he married a hugely wealthy heiress, Marie-Felix Blanc, the daughter of François Blanc who had founded the Monte-Carlo Casino and la Société des Bains de Mer (Monaco). In 1882, just a month after the birth of their only daughter Marie, Marie-Félix died from a pulmonary embolism at the residence in Saint-Cloud. Thereafter, Roland decided to dedicate the time and money at his disposal to his passion: science.

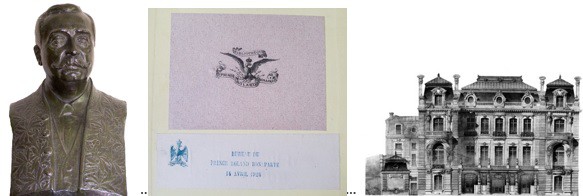

He had a predilection for geography, in all its forms: cartography, geology, anthropology, natural sciences, and photography. He organised expeditions to Italy, Germany, Corsica, Lapland, North America from where he returned with a number of scientific objects and Napoleonic souvenirs. He soon needed a house worthy of his collections and name, and so between 1892 and 1896 he built a mansion on the avenue Iéna in which he would be able to house, among other things, the 150,000 volumes from his library!

A great patron of the sciences, he particularly liked technological innovations; for example, he funded Charcot’s expedition to Antarctica, a zoological observation ship and Balachoff’s photographic balloon recording device… He became a member of dozens of scholarly societies (Académie des Sciences, Société Botanique de France, Société de Géographie) and often presided over them, indeed he became the president of the Académie des Sciences in 1920, which, along with his other positions, solidified his recognition as a scientist.

The Bonaparte Herbarium

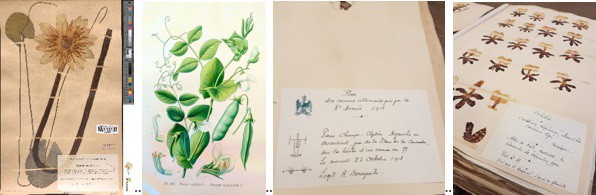

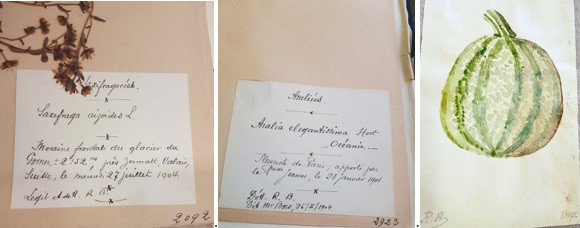

From 1900 Roland launched himself into his project of creating a comprehensive herbarium which contained “useful” plants from around the world. He managed to assemble in a few years the most important collection of dried plants ever assembled by acquiring the collections of the best botanists from the period (such as Georges Rouy), by sending scientists to the end of the world and by getting in touch with all the colonial outposts, as his rich botanical correspondence (bequeathed along with his herbarium) perfectly highlights.

Roland never missed the chance to add to the collection himself, wherever he was: on an excursion, in congress, on holiday. He also grew thousands of varieties of useful plants (edible, dye or medicinal) in his garden at Saint-Cloud. Close to half of the species of flowers from around the world were also found in this incredibly vast collection, and many of the specimens are unique for science as they represent species which are otherwise extinct. There is also the chance to admire the historic or more personal treasures such as water-colours done by himself or his daughter, flowers taken from bouquets offered to the princess, or taken from Christmas baskets.

After Roland’s death in 1924, his daughter Marie, who became the Princess of Greece and Denmark, financed the transfer to the University of Lyon of Roland’s collection.

Due to the lack of space, only the ferns, which became the Prince’s speciality at the end of his life, could be preserved by the Natural History Museum in Paris. It took no less than 22 wagons to transport the 8,800 herbarium boxes, 3,175 boxes or jars and 1,800 books and brochures.

And now?

The digitisation of Roland Bonaparte’s herbarium has allowed a safeguard of this precious heritage and it is massively accessible to everyone. It has led to the use of some of the most modern types of research, for example using artificial intelligence, something of which the Prince himself would have approved. But work still remains: all the data relating to the collection of these samples still needs to be digitised. Everybody can help by taking part in the Herbonautes Programme (French) where the game is to decipher and fill in the information given on the herbarium labels such as the year and place of harvest or the collector’s name.

There are also dozens of collections to digitise in the herbarium at the University Lyon-1, which are made up of hundreds of thousands of sheets, which represent the collective trace of the campaigns of plant collecting since the 18th Century.

Mélanie Thiébaut, Doctor at Lyon-1 and director of Lyon-1’s Hebarium

To support, ask questions, or send in suggestions on the project | Website (French) | Facebook Page (French) | Twitter Account (French) | Instagram (French)

March 2019 (English translation by Rory MacLean)