Of all the existing images of the Empress Eugenie, the photographs of her in prayer are the most iconic. This photographic portrait taken by Gustave le Gray in the summer of 1856 for the painter Thomas Couture, was widely disseminated after it was taken.

This wasn’t the first time the Empress was captured in prayer; the sculptress Marie Louise Lefèvre-Deumier (1816-1877) created a small sculpture on the occasion of the imperial marriage on 30 January 1853, which showed the Empress kneeling on a prie-dieu draped in a fabric bearing the imperial coat of arms.

The Empress’ attire was thus described in the memoirs of her contemporaries: the dress was made of ‘white, velvet épinglé fabric, studded with stones’; she wore a tiara of diamonds and sapphires; her tulle veil was held in place by a chignon decorated with orange blossoms. This photograph reflects the image of the perfectly pious wife and mother (as per 1856); one who had provided France with an heir. This ‘ideal’ depiction of motherhood was promoted by the Empire. However, the photo also highlights another side of Eugenie’s personality.

As a child, the future Empress, Eugenie de Guzman Palafox, or Montijo, Comtesse de Teba, spent a year in a convent school in Paris (the Couvent de Sacré-Cœur), which provided the sort of religious education favoured by the Catholic aristocracy of the 19th century.

She was very pious and was disappointed not to have received the holy sacrament from Pope Pius IX at the time of her marriage to Napoleon III. She was compensated in this regard when her son, the Prince Imperial, was baptised by the Sovereign Pontiff in 1856; she was also presented with a golden rose. This beautifully crafted, gold-plated flower is the most prestigious gift that can be bestowed (to a woman) by the pope(The Empress always kept this gift with her, even during her exile in England. It was later put on display at Farnborough Abbey, where it was stolen a number of years ago.).

As Empress, Eugenie was in the public eye, and her personality, character traits, and values were on display to the people of France. She expressed her Catholic faith through what her contemporaries referred to as a “Ministère de la Charité” ‘Ministry of Charity’(Lettre du 3 mars 1866, de Mgr Darboy à l’Impératrice.). She distributed financial support to the causes and institutions she deemed to be important, with funds from the coffers of the Ministry of the Interior.

In addition, she took out a life insurance policy worth more than 2 million francs so that her charitable work would be able to continue after her death. As well as distributing of money to hospitals, orphanages and prisons, she made daily visits to the suffering and needy. Because of her visits to the sick, especially during the cholera epidemic in 1865, the people of France saw her as gentle and benevolent. She was seen as the “bonne impératrice, source inépuisable de consolations et de charité” [“the good Empress, (an) inexhaustible source of consolation and charity”].(Michelet M., L’impératrice Eugénie. Une vie politique, Paris, Les Éditions du Cerf, 2020.).

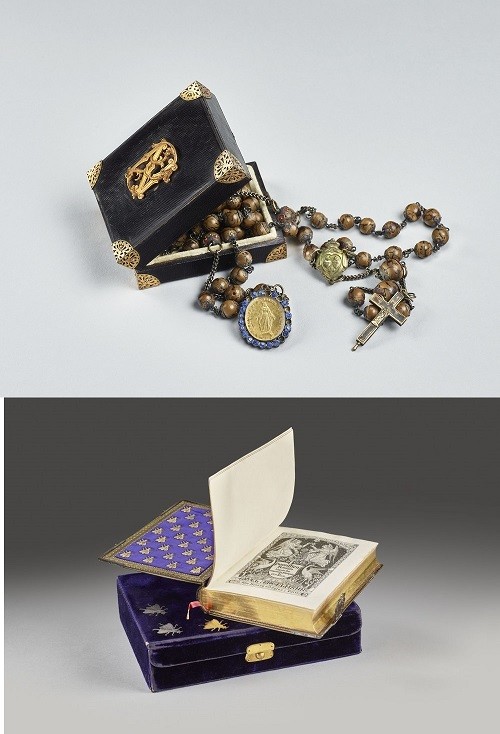

Although her detractors considered her a bigot, Eugenie found a particular comfort in her religious beliefs, especially during periods of personal difficulty. She expressed her faith with personal devotional objects which, despite all, remain precious and charged with emotion. Two of these personal objects now belong to the Fondation Napoleon: her rosary beads and her prayer book.

The rosary is a simple unfussy one. It is made of boxwood beads, with a chain, a cross, and an oval medallion in gilded silver. It is easy to imagine them in the hands of the Empress as she prayed in a palace chapel. They are kept in a rectangular wooden box covered in morocco leather, decorated with delicate corner reinforcements and a gilded N and E on the lid (the cypher of Eugenie and Napoleon).

The medallion on the rosary indicates its origins. It is dedicated to Notre Dame de la Trappe de Staouéli (Trappist monastery in Algeria) and was probably given to the imperial couple on their visit to the monastery in Algeria on 4 May 1865 (Account – in French – of the Emperor’s visit to the monastery). The monastery was founded in 1843 on the site of the Battle of Staouéli (which took place on 19 June 1830 and preceded the capture of Algiers on 5 July and the later conquest of Algeria) and aimed to establish a religious community in the territory through its involvement in the region’s agriculture. The Emperor’s visit thus represented a recognition of the work accomplished by the Trappists.

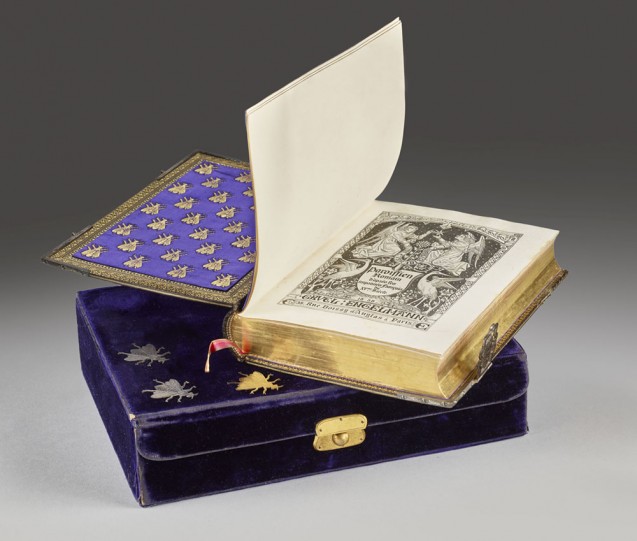

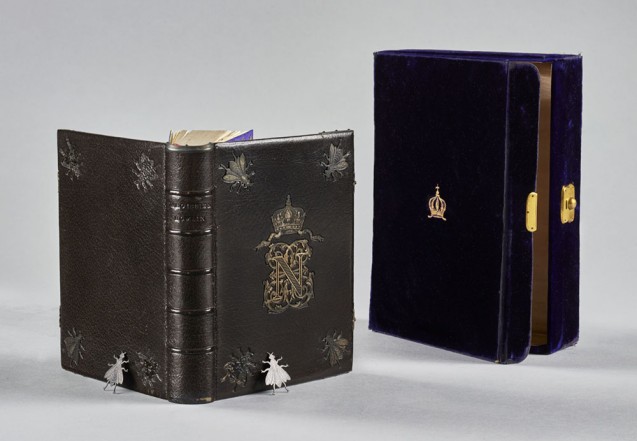

The second object is Eugenie’s prayer book. This missal is peculiar in that it is printed with decorations and illuminations imitating those of the 15th century. It is bound in dark brown grained calfskin with the double initials of the Empress beneath the imperial crown and silver niello-inlaid bees at its four corners. Published by Gruel and Engelman in 1858, the Paroissien Roman [Roman Parish Missal] was widely distributed at the time of its publication.

This copy is kept in a velvet case decorated with the imperial crown made by Jenner and Knewstub (producers of spectacular cases and boxes, who presented their work at the Exposition Universelle of 1862, and were among Queen Victoria’s official suppliers). It was probably purchased while the Empress was in exile and in all probability bore witness to tragedy: there is a handwritten note inside the book which mentions the date of her husband’s death (9 January 1873). We don’t know the reason for the note, and we don’t know whether or not it is in Eugenie’s hand, but it is conceivable that she was reading the missal to the fallen Emperor during his last moments.

A few years later (around 1892), Eugenie took a similar pose when she sat for a portrait by the photographers W&D Downey. In this photograph she can be seen wearing a black dress and holding a bouquet of violets. She was still in mourning for her husband and her son, who had been killed in the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879.

Far from the public and political sphere where it was fashionable to be seen as pious and irreproachable, the Empress Eugenie seems to have been able to find genuine relief in the intimacy of her faith (and not the bigot of her enemies attacks). These two objects in the collection at the Fondation Napoleon bear witness to her spiritual aspiration.

Élodie Lefort, June 2020 (translation JR)

Rosary belonging to the Empress Eugenie

Second Empire

materials: Boxwood, silver, beads, gilded metal

Height: 7.5cm (rosary: 63cm); Width: 6cm; Depth: 2.8cm

INV 289, Fondation Napoléon, Paris

© Fondation Napoléon / Thomas Hennocque

Prayer Book belonging to the Empress Eugenie: The ‘Paroissien Romain’ in the style of French 15th century print

1858

materials: Morocco leather, bearing the cypher of Eugenie, silver, velvet

Height: 16cm, Width: 13cm

INV 290, Fondation Napoléon, Paris

© Fondation Napoléon / Thomas Hennocque