In June 2018, the Musée du Louvre issued a press release* informing the general public that they had solved a mystery more than 150 years old. Since 1862, the museum has owned a bronze finger, 38 cm in height, clearly a fragment from the hand of an ancient statue. The only thing we knew about this finger is that it was bought by Napoleon III when he acquired part of the Campana collection during the Second Empire. Apart from that, the finger’s history and provenance were unknown.

The Campana collection, and the ephemeral “Napoleon III Museum”

The Marquis Giampietro Campana (1808-1880) was Director of the Vatican Monte di Pietà (Mount of Piety, an institutional pawnbroker which was part of the Pontifical Treasury). Campana was an art collector like his father and grandfather, and he built up an exceptional collection, including archaeological objects, paintings by the Italian Primitives, paintings from the Italian Renaissance, sculptures and objects. However, abusing his position as director of the pawnbroking institution, Campana used funds from it to enrich his collection. He was arrested in 1857 and sentenced in 1858 to twenty years in prison, his sentence being finally commuted in 1859 to life-long banishment, with confiscation of his property. Pope Pius IX took possession of the collection, which was renowned throughout Europe, and set about selling it. Discreet negotiations were held with Napoleon III, who was close to Campana and his British wife Emily Rowles (whom he had known in Chislehurst, Kent, and in whose former house he would finally settle when he returned to Britain in exile), but the Emperor found the first price too high. In the end, the first lots were acquired by Great Britain in 1860 for the South Kensington Museum (now Victoria and Albert museum), and then by Russia in 1861 for the Hermitage Museum. These purchases led French cultural circles to increase the pressure on Napoleon III to make a move. In 1863, Belgium finalised the acquisition of a set of vases hidden by relatives of Campana from the Pontifical State.

In order to keep a low profile, the Emperor did not send Count Nieuwerkerke (1811-1892), director general of the imperial museums and future superintendent of Fine Arts (in June 1863), to negotiate the price, but rather the historian Léon Rénier (1809-1885) and the painter Sébastien Cornu (1804-1870; husband of Albertine-Hortense Lacroix, whose parents had been in the service of Queen Hortense). On 20 May 1861, a contract was signed for the sale of 11,835 items from the Campana collection for the sum of 4.36 million francs. The law of 2 July 1861 allocated a credit of 4.8 million francs to set up a “Napoleon III museum” to house this collection, as well as the pieces resulting from imperial archaeological excavations in the Middle East.**

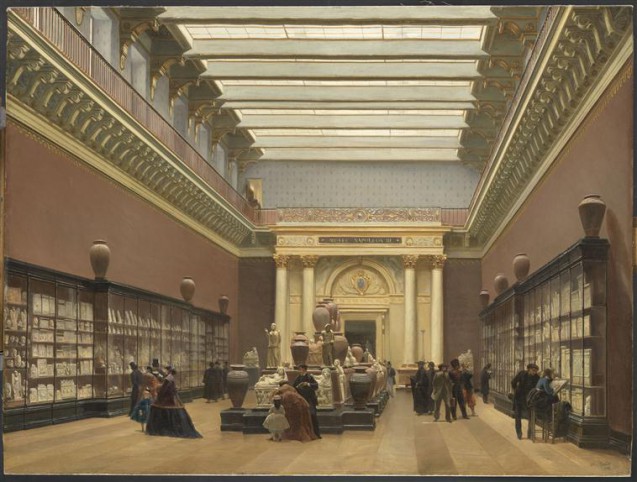

The purpose of this “Musée des arts appliqués à l’industrie” (“museum of the arts applied to industry”) was to propose an overview of techniques and their evolution through didactic series of works, in order to encourage the development of industrial and decorative arts by providing models of inspiration and reflection.*** Whilst rooms at the Louvre Museum were being prepared to accommodate the works, the “Napoleon III Museum” was temporarily housed in the Palais de l’Industrie. It was inaugurated on 30 April 1862, and opened to the public on 1 May (the same day as the opening of the Universal Exhibition in London), and was a huge success. Several hundred tickets were distributed to allow professionals (scholars, workshop managers, artisans) to prolong their study of the exhibits outside of official museum hours.**** A guidebook was also published based on articles by Ernest Desjardins from the Moniteur (a copy can be seen here on Gallica).

The closure of the “Napoleon III Museum”, initially scheduled for 1 August, was postponed to 31 October by Imperial Decree of 12 July 1862 (due to the delay in the work on the Louvre). The same decree confirmed the decision to transfer a large part of the works into the Louvre’s collections and to send a selection of pieces to provincial museums, with a view to developing a “seed-bed of museum-schools in all departments”.****

The decree of July 1862 was issued as heated discussions were taking place between, on the one hand, those who supported Napoleon III’s decision to unite most of the works on display with those in the Louvre Museum to create an encyclopaedic overview, and on the other hand, those who favoured a “Napoleon III museum” independent of the Louvre, focused on the industrial arts.

In addition to the Louvre, two other museums in Paris received works: the Musée du Moyen Âge de Cluny and the Musée de la Céramique de Sèvres. Outside of Paris, the museums of Montpellier and Nantes, considered to be the most important at the time, but also those of Lyon, Avignon, Lille, Dijon, Metz, and many others, were attributed works, the number and quality of which depended on whether the establishment belonged to the first, second or third category of museum classification.

On 15 August 1863, new rooms were opened at the Louvre Museum, where the public could admire the so-called “Sarcophagus of the Cerveteri Spouses”, and “The Battle of San Romano: the counter-attack by Micheletto da Cotignola” by Paolo Uccello.

RMN / Jean-Gilles Berizi 1997

2018: the finger is reunited with its hand…

It was during a research project on the technique of manufacturing large antique bronzes conducted by the Louvre Museum and the Centre de recherche et de restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF)*, that the finger was finally reunited with its original hand. A resin copy was made to confirm the discovery of the Louvre’s curators: this finger was missing from the hand from the monumental statue of Emperor Constantine, held by the Capitoline Museum in Rome (together with the head of the same statue, the globe probably carried by this hand, and a foot: see a video of the museum room with these pieces).

Irène Delage, September 2018 (translation RY)

* Read the press release from theMusée du Louvre (in French)

** Arnaud Bertinet, “L’achat de la collection Campana”, in Napoléon III, le magazine du Second Empire, 2011, n°48, pages 25-29. Arnaud Bertinet was the recipient of a study grant from the Fondation Napoléon in 2004, and the author of Les musées de Napoléon III. Une institution pour les arts (1849-1872), edited by Mare et Martin, in 2015.

***Isaline Deléderray-Oguey, « La collection Campana au musée Napoléon III et la question de l’appropriation des modèles pour les musées d’art industriel », Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre [online], 11 | 2017, 26 october 2017, consulted on 28 August 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cel/721 ; DOI : 10.4000/cel.721

**** Arnaud Bertinet, Les musées de Napoléon III. Une institution pour les arts (1849-1872), published by Mare et Martin, in 2015 : see p. 239-309 and p. 403-412.

From 7 November 2018 – 11 February 2019, there was an exhibition at the Musée du Louvre, A Dream of Italy: The Marquis Campana’s Collection.