From one Empire to another

After the fall of the Empire in 1815, Napoleonic emblems were banned. The Eagle and the Tricolour flag were no longer to be brandished by the army, to be replaced by the Fleur de lys and the white flag of the Bourbons. During the July Monarchy, the Tricolour was rehabilitated in order to promote national harmony, and the “Coq gaulois” [Gallic Rooster] (in place of the Eagle or Fleur de lys) went on top of the military standards. In 1848, the red flag [which had been the symbol of martial law during the French Revolution] was briefly envisaged before being replaced by the bleu-blanc-rouge (blue-white-red) flag of the Revolution and the Empire. The Rooster, which had become the symbol of a bourgeois monarchy, was replaced by the Spearhead and an ammunition case stamped with the letters “R.F.”

The Second French Empire, in memory of victories past, brought back the Eagle as the symbol of the State and the Army.

Description

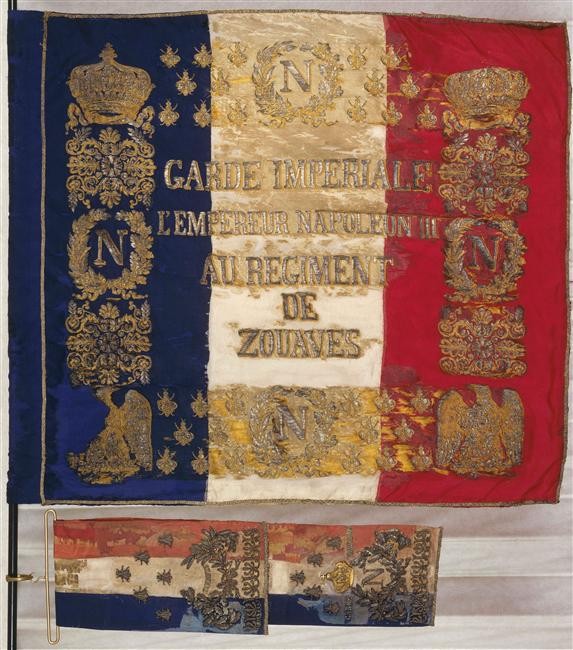

The three colours – with blue closest to the pole, followed by white and red – are arranged in vertical bands. The standard is made of a single piece of silk brocade measuring 90 x 90 cm, with three strips sewn together for the coloured lines. The silk is framed vertically by large embroideries made of gold “cannetilles” [gold thread twisted around a central metal thread] representing, on each side: an imperial crown, an “N” surrounded by laurels and a palmette [small motif representing a stylised palm tree]. These vertical bands arranged symmetrically, are joined at the top and the bottom by a frieze of embroidered bees and two more “N”s with laurels. In the centre of the flag is a five-line embroidered inscription: GARDE IMPERIALE/L’EMPEREUR NAPOLEON III/AU REGIMENT/DE/ZOUAVES [IMPERIAL GUARD/THE EMPEROR NAPOLEON III/TO THE REGIMENT/OF/ZOUAVES].

Historical Context

As soon as he came to power, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, then Prince-President of the Republic, wished to bring back the Imperial Eagle. It was by a decree of 31 December 1851 that the Prince-President of the Republic ordered that the Eagle be reinstated as the symbol of the French armies. The proclamation begins thus: “The President of the Republic, considering that the French Republic in its new form sanctioned by the people can confidently adopt the memory of the Empire and the symbols that recall its glory: Considering that the national flag should no longer be deprived of the renowned emblem that led our soldiers to victory in a hundred battles:…”.

Whilst the emblem of the Republic (the Spearhead) was replaced by the Eagle, the three vertical stripes (blue at the shaft, white and red) adopted in 1812, and reinstated by Louis-Philippe, were kept. The inscriptions, however, were modified. The letters “LN” for Louis Napoleon were set inside laurel and oak leaf wreaths, on the obverse and the reverse, in the top corners on the staff side and bottom corners on the free edge. The second diagonal bore the regimental numbers. The obverse of the flag was inscribed: “LOUIS NAPOLÉON AU [number of] REGIMENT”, while the reverse side retained the letters “R.F.” (République Française) followed by the names of the battles.

The Directorate of Artillery was responsible for overseeing the design of the 190 emblems that were ordered. The fabrics, whose inscriptions were to be painted, were made in the Marion workshops. The modelling of the Eagles was entrusted to the sculptor Auguste Barre; and the pieces were executed in gilded bronze by the Vittoz founders.

On 10 May 1852, in an imitation of the 1804 distribution ceremony, the new flags were blessed and presented with great pomp to the regiments on the Champ de Mars.

The proclamation of the Empire did not immediately modify the more recent emblems of the units of the line, however a new military standard based on the one of 1812 was to be created. It was not until 11 November 1853 that the presidential formula would be replaced by the inscription “L’EMPEREUR NAPOLÉON III Ne RÉGIMENT” [“EMPEROR NAPOLEON III [number of] REGIMENT”] and the “R.F.” would be replaced by crowns.

In April 1854, the units received these new emblems, without any grand ceremony this time. In 1848, the reformed military standards of Louis-Philippe had been sold, much to the anger of the army, so this time Napoleon III decided to have the old emblems of the line destroyed.

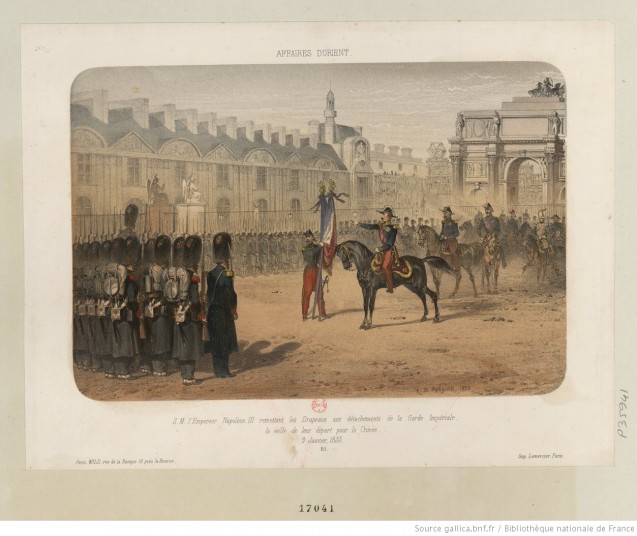

When the Imperial Guard units were created in May 1854, the Eagle was not modified, but the silk standards were made much more luxurious. In particular, the inscriptions and decorative elements were now embroidered instead of painted as they had been in those of the line regiments. In addition, this renaissance of the Imperial Guard regiments was also an opportunity to honour the historical victories of these prestigious units. Thus, the flags of the Lancers regiment commemorated the Battle of Somosierra, those of the Carabiniers-à-Cheval recalled the Battle of Eckmühl and those of the Chasseurs were decorated with inscriptions paying homage to the victories at Marengo and Austerlitz. Later on, the victories of the Second Empire were added: Sebastopol, Magenta etc. The first emblems were solemnly presented in the courtyard of the Tuileries Palace on 9 January 1855, the eve of the departure of two regiments of the Guard Infantry for the Crimea.

As was customary with the sovereign’s Garde, the emblems of the Imperial Guard were deposited at the Tuileries directly in the Emperor’s office. During ceremonial drills and inspections, it was up to the squadron of the “Cent Gardes” [the Hundred Guards] to take the emblems and hand them over to the units that were going to undergo the inspection using a specific ceremonial procedure. For the soldiers, the emblem was a powerful symbol of their belonging to the army; for the soldiers of the Guard, furthermore, the symbol of the Eagle had an almost sacred connotation of inheritance from the First Empire. Therefore, from 1861 onwards, there was no longer any question of destroying the reformed emblems of these Praetorian units. They were now to be deposited by the Cent Gardes at the Artillery Museum at the ex-convent of Saint-Thomas d’Aquin in Paris. The first such ceremony took place on 27 September 1861.

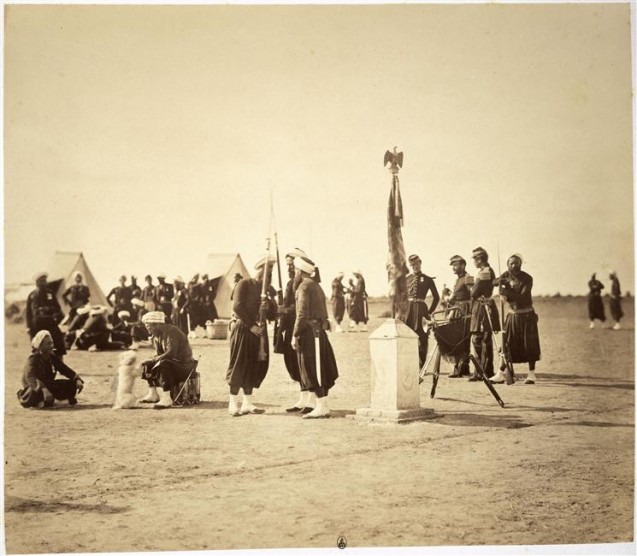

The reign of Napoleon III was a period of war in which French units often had the opportunity to distinguish themselves – in Crimea, Italy, China or indeed Mexico. Capturing a flag from the enemy was an act that illustrated the valour of a soldier as an individual. However, during the Second Empire, the Légion d’Honneur was awarded symbolically to the unit’s flag, so that the bravery of one would reflect on all. Thus, on 4 June 1859, after the Battle of Magenta, the 2nd Zouave Regiment would have its Eagle decorated, as later did the 51st and 99th in Mexico, or the 57th line after Rezonville in 1870.

During the disasters of 1870, numerous French flags were captured as well as destroyed. Indeed, as a final act of resistance, during the surrenders at Metz or Sedan, many of the Guard units cut their own flags into pieces and scattered them around, or even burned them, whilst the Eagles were hammered and broken. In Metz, not all the generals had time to have their emblems destroyed, so, as was the convention, more than fifty flags were handed over to the Prussians.

François Houdecek

March 2020

Sources

– Ortholan, L’armée du Second Empire, 1852-1870, Paris, Soteca, 2009.

– Le Pointe, Histoire de nos flags de 1792 à nos jours, leurs légendes et leurs gloires, Paris, H. Jouve, 1909.

– Lt col Rousset, Histoire générale de la guerre Franco-Allemande (1870-1871), Paris, Jules Tallandier, 1912.