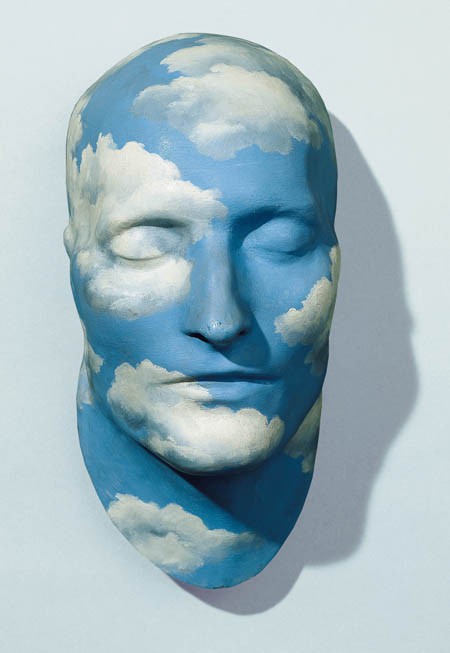

Magritte made four versions of this work, “L’Avenir des statues” (‘The Future of Statues’), in the period 1933 to 1937. He took a commercial plaster version of Napoleon’s death mask and painted onto it a deep-blue sky spotted with sunlit clouds. According to David Sylvester, it is only the polish on the plaster and the density of the clouds which makes relative dating possible. The title, invented by the poet and philosopher Paul Nougé and not the author himself, says little concerning the artist’s intentions.

That being said, the fact that the piece is a plaster death mask of Napoleon, painted like a “ready-made”, poses the question (implied by the title) of the sculptural quality of the object. The fact is, there are several versions of this mask, and none of them can be considered as the imprint of a natural object, since the features of the corpse were idealised post factum with a view to the mass-reproduction and diffusion of the mask. It is these corrections performed on the mask used by the artist which bestow on the mask its status as a sculpture. As for Magritte, however, since he did not produce the plaster in his atelier, he did indeed “paint a ready-made”. His contribution was limited to the painting, and the title invented by Nougé riffs on the Italian tradition of the Paragone, which claimed that painting, by the hand of the artist, would in the end overcome sculpture, a medium here represented by a mass-produced industrial product.

Furthermore, the motif painted on the mask by Magritte could be evocative of the expression “to have your head in the clouds” and could be interpreted, with one eye on the title “The Future of Statues”, as an expression of the high esteem which Napoleon had of himself, even of his arrogance. The death mask is essentially a portrait of the sovereign at the lowest point in his career: deposed after his defeat at Waterloo, exiled and indeed already dead. The innovative element here is the portrayal of the mortality of the sovereign, in opposition to the monumental tradition which more often glorified Napoleon. Luigi Calamatta gives a fine example of this practice in an engraving dated 1834 which presents the same death mask but associating it with the attributes of the fallen Emperor and suggesting his eternal glory. Magritte, on the other hand, uses clouds to cover and blur Napoleon’s features hinting at the fleeting nature of his glory and, what is more, to reveal the true nature of such effigies of sovereigns: the latter only exist via the images which are projected upon them. The painter expressed this idea in a similar way in 1927 in his painting “La Forêt” (The Forest) in which figures a sculpted head bearing the face of the Emperor. Instead of using the typical image of the sovereign wearing a laurel wreath, he paints over a veil of ordinary leaves and branches over Napoleon’s face, thereby depriving the head of any symbolic meaning. As for what Magritte himself thought of the expressive of force of symbols, he remarked: “Symbols […] ought to provide an image of reality, but in fact they say nothing about this. If you look at something with the aim of discovering its meaning, you end up not seeing the object itself but merely thinking about the question you asked yourself on looking at it.”

The question here is: What is the Future of statues? And on the subject of this work by Magritte, the author of the title, Paul Nougé, replied in 1933: “Thanks to Magritte, the result is that, in a completely unforeseen way, the plaster cast of Napoleon, […], a forest ajar, a block of sky shot through with clouds and dreams, transfigures the very face of death.”

Marion Bornscheuer

Curator at the Lehmbruck-Museum

(translation: Peter Hicks)

April 2016

This work was part of the temporary exhibition Napoléon à Sainte-Hélène. La conquête de la mémoire, (Napoleon on St Helena, His Fight for his Story) at the Musée de l’Armée, Paris (6 April – 24 July 2016).