The Belgian painter Alfred Stevens was born in Brussels in 1823 and moved to Paris in the 1840s. His early works, such as portraits of soldiers or social scenes, were part of a pictorial trend that emerged in both France and Belgium at that time, that of social-realism. It is in this context that he presented the painting “Les Chasseurs de Vincennes” [The Light Infantrymen of Vincennes] which was presented at the 1855 Exposition Universelle under the title “Ce qu’on appelle le vagabondage” [“This is what they call “vagrancy””], together with three other paintings, namely “La Sieste”, “Le Premier jour du dévouement” and “La Mendiante”. In the photographic album of the exhibition realised by Eugène Disdéri, the painting “Ce qu’on appelle le vagabondage” by Stevens can be identified on page 14, bottom left.

The painting in its historical context

With this representation of a homeless mother and her two children being escorted by soldiers (“chasseurs à pied” or light infantry who were garrisoned in Vincennes), Stevens approaches the theme of poverty from a political rather than a social angle, choosing to depict not only individual generosity (represented by the wealthy woman attempting to intervene with the soldiers), but also State repression. The State, personified here by the soldiers (one of whom appears to reject the charitable gesture of the wealthy lady), does not protect but rather seems to consider the homeless mother and her young children (the weakest and most fragile in Society) as harmful, dangerous, even criminal.

The choice of the wintry season, the gloomy light, the dark shades of the clothes and uniforms, the absence of a horizon (blocked by the dark grey wall in the background which fills the entire width of the painting), the simplicity of the characters (the soldiers, cold and business-like, the mother resigned, the lame worker with his crutch, the tearful child, and the wealthy woman attempting generosity) all contribute to making this scene spontaneously moving.

Reactions to this painting at the exhibition were varied; some critics talked about the moving qualities of the scene (Ernest Gebaüer, for example, here in French on Gallica), while others, such as Maxime Du Camp (also in French here on Gallica), point out a certain artistic anomaly, the left foot of the kind passer-by being strangely distant from her body.

on the website of the BnF: have a look at this image enlarged with possibility to zoom

Over the 19th century in France, law and order, in other words the management and control (meaning surveillance and repression) of individuals liable to disrupt the social order, became increasingly a popular issue. A worker’s record book, in effect, a passport for use within national borders, and the version of this document issued to those who fell into indigence, served not only for identification but also for the surveillance of a worker’s movements; it could also be used to track itinerant merchants, street artists, the indigent and the vagrant. A decree dated 5 July 1808 “for the eradication of begging” had prohibited begging and created departmental depots where able-bodied beggars would be taken in and employed. The attribute “vagabond” made the situation worse, with “vagrant beggars” being taken to detention centres. The 1810 Penal Code considered begging a crime (arts. 274 and 275); vagrancy likewise (art. 269). Whilst beggars were not clearly defined, vagrants were clearly identified as “unscrupulous people [namely] those who have no certain place of residence or means of subsistence and who do not exercise any trade or profession” (art. 270). Beggars and vagrants could be sentenced to from three to six months’ imprisonment, or even two to five years if they were carrying weapons. This sentence could be followed by a further period of enforced labour in begging depots. During the Second Republic, the electoral law of 31 May 1850 operated a further ostracism, separating the homeless from the rest of society by prolonging the period of residence required in order to be able to vote in a particular commune or canton, from six months (law of 15 March 1849) to three years.

The career of Alfred Stevens

Alfred Stevens (Brussels, 1823 – Paris, 1906), studied with Ingres at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-arts de Paris, was a close friend of Manet, and also frequented Delacroix, Degas, Bazille, Courbet, Morisot… and the French author and playwright Alexandre Dumas fils, the latter being best man at his marriage. His father collected works by Delacroix and Géricault, his brother Joseph was a painter and engraver, and his brother Arthur, an art dealer based in Paris and Brussels.

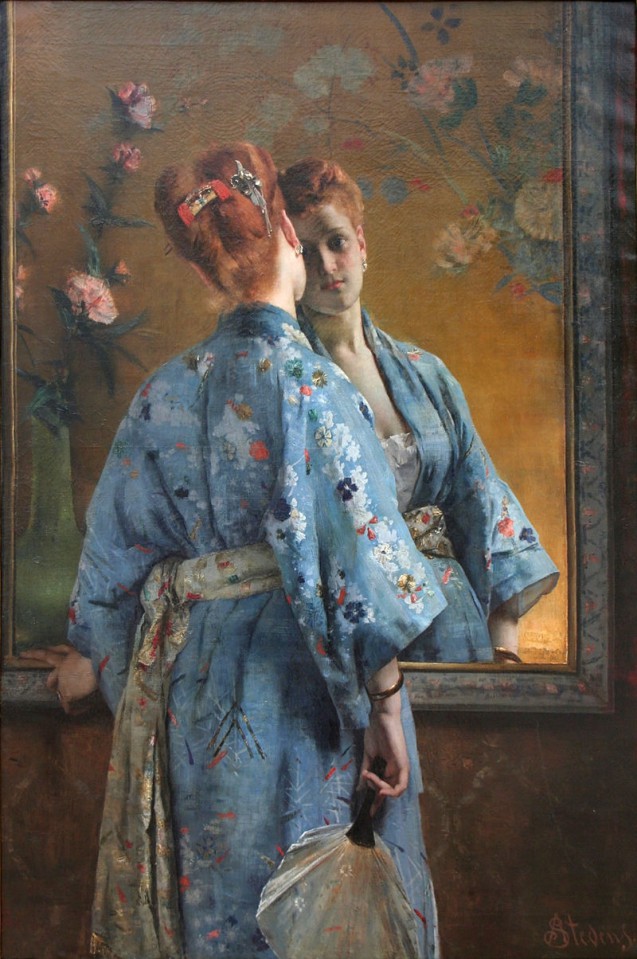

With both the Princess Mathilde and Princess de Metternich as patrons, Stevens was very successful during the 1860s and 1870s, portraying women of the aristocracy and the upper middle class, celebrating the elegance and refinement of interiors and images of domestic bliss. Like many of artists at the time, he was also interested in Japanese art, and in 1867, he won a gold medal at the Universal Exhibition. From the 1880s onwards, he went through an existential and artistic crisis, profoundly reconsidering his work, and went on to join the Impressionist movement, painting landscapes and seaside scenes.

In 1886, Stevens’s book Impressions sur la peinture [Impressions on Painting] was published, (available on Gallica), including such personal reflexions as:”Géricault with a single figure tells us the story of the whole First Empire” (LXVIII) and “the historical subject was invented from the moment people stopped being interested in painting itself”.

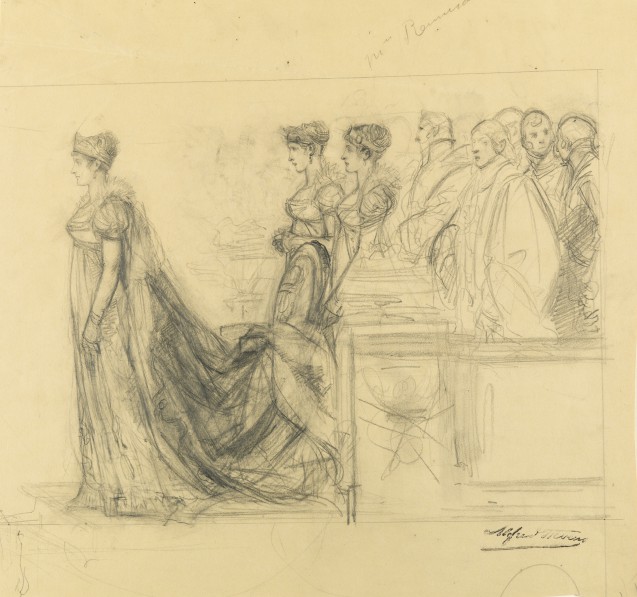

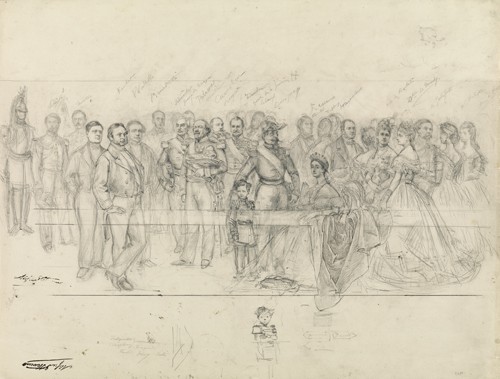

Alfred Stevens, together with Henri Gervex (1852-1929), was asked to produce a “Panorama of the History of the Century”, to be exhibited during the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition. Several preparatory drawings can be found in the collections of the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique [Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium] (as well as those of the Petit Palais, Paris, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris). These include an “Empress Josephine and her court” (Inv. 11659), and a “Napoleon III with his Court and his generals. Group with Napoleon III, Empress Eugenie and the Prince Imperial” (Inv. 11666) (see illustrations below). The panorama was exhibited for seven years in a rotunda at the Tuileries (a poster for which can be seen here on Gallica). Afterwards the painting was cut into about sixty pieces, and shared out between the shareholders of the Société anonyme de l’Histoire du siècle [Limited Company of “The History of the Century”] which had been created in order to finance the realisation of the panorama.

© Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels / photo: J. Geleyns – Art Photography

central group with Napoleon III, Empress Eugenie and the Prince Imperial”, by A. Stevens, 1889

© Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels / photo: J. Geleyns – Art Photography

Irène Delage, October 2018 (translation RY and PH)