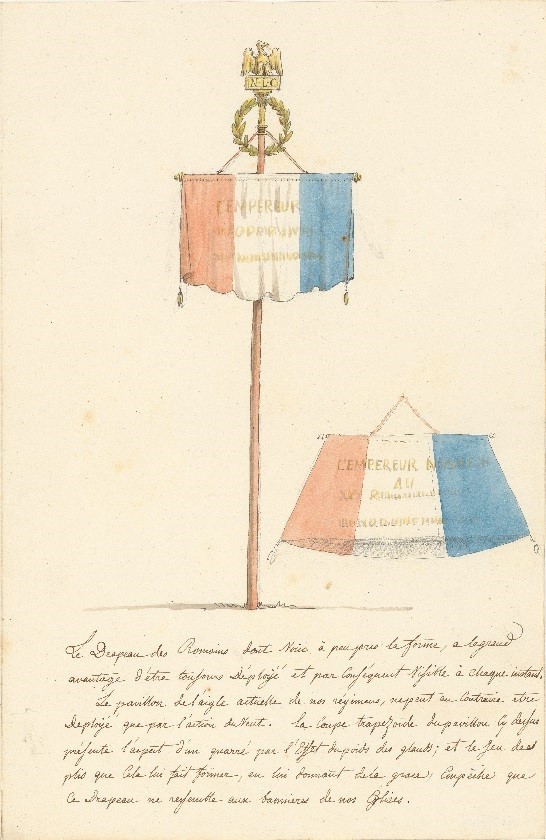

David recommended that the standards be made in a shape known as “à la romaine”, namely a trapezoid of cloth mounted on a crossbar. The painter, whose trained eye was sensitive to movement explained the reason for this choice:

“The flag of the Romans (…) has the great advantage of always being unfurled and therefore visible at all times. The current eagle flag of our regiments, on the other hand, can only be unfurled by the action of the wind.”

David also responded specifically to the Emperor’s wish to avoid any resemblance to the religious banners carried in processions:

“The trapezoidal cut of the flag (…) presents the aspect of a quarré [square] as a result of the weight of the tassels; the play of these folds formed by the latter, rendering it quite graceful, prevents this flag from resembling the banners of our churches.”

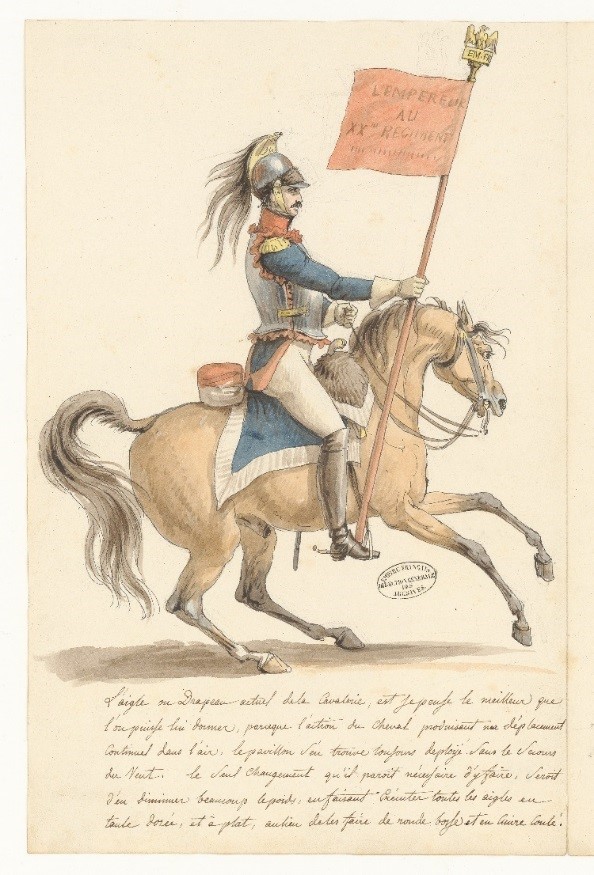

The question of movement, which was obviously important to David, is also explicit in his analysis of the cavalry flag (above):

“[The current one] is I think the best one that we can provide, because since the action of the horse produces a continuous movement in the air, the flag will always be deployed without the help of the wind.”

Decorum and uniforms

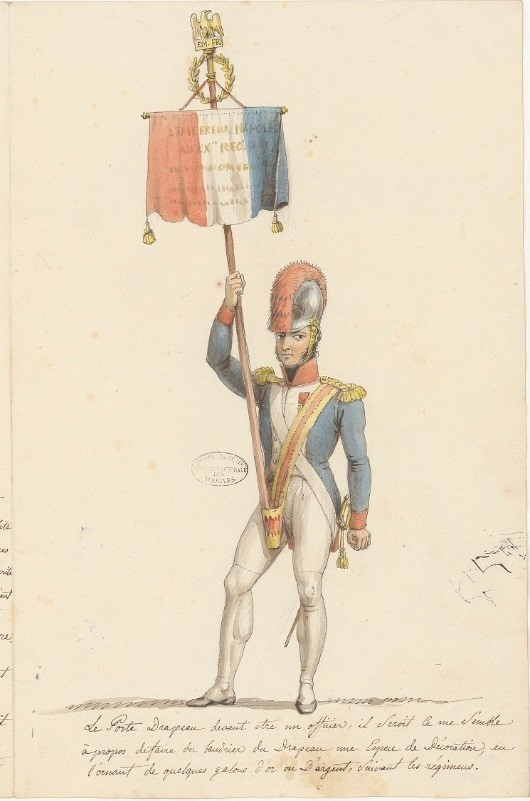

The painter also took the liberty of making suggestions for the standard-bearer’s uniform, to which he wanted to add more decoration, again showing his concern for graphic detail:

“As the standard bearer is necessarily an officer, it would be appropriate, it seems to me, to make the shoulder strap supporting the flag into a kind of decoration, by adorning it with a few gold or silver braids, depending on the regiment.”

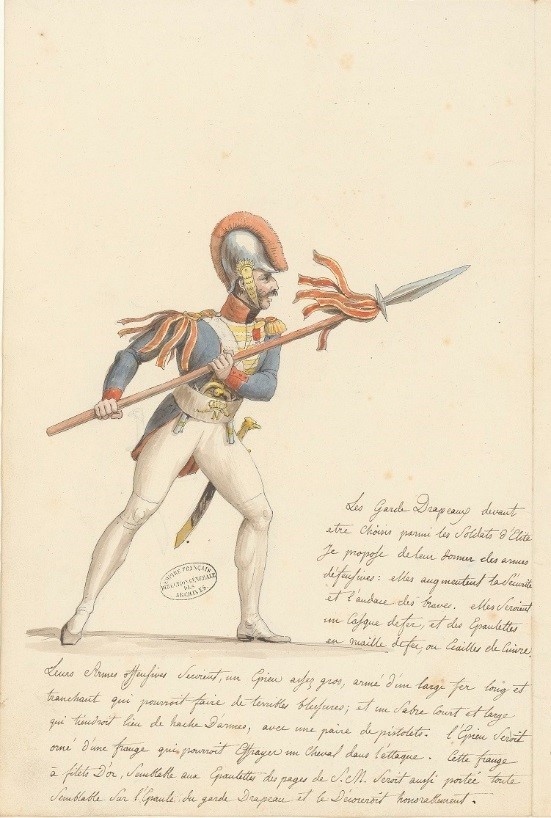

David went even further, even proposing new arms for these men, in order to signify the honour they have been bestowed by being entrusted with the flags.

“Since the standard bearers are always chosen from among the elite soldiers, I propose to give them defensive weapons: they would increase the safety and boldness of these brave men. This defensive equipment would consist of an iron helmet and epaulettes made of iron mesh, or brass plates. For their offensive weapons [I suggest] a fairly large sword, bearing a broad, long, sharp blade capable of inflicting terrible wounds; and a short, broad sabre that would take the place of the poleaxe, together with a pair of pistols. The sword should be adorned with a fringe which could frighten a horse in the attack. This fringe made of golden threads, similar to the epaulettes of His Majesty’s pages, would also be worn in the same way on the flag-carrier’s shoulder and would decorate him honourably.”

David thus wished to combine military efficiency with pomp and circumstance. In so doing, however, he largely overstepped his initial instructions; the choice of arms was not simply a matter of “style”, one might say, but above all a choice dictated by efficacity on the battlefield. It was therefore not the artist’s job to express himself on this point.

Were the Eagles too heavy?

As per the Imperial decree of 25 December 1811 on eagles, flags and standards, it was to be from the Emperor himself the armies were to receive the eagles ensign, and they were to swear an oath to defend it, even to the death – this ceremony was the one illustrated in 1810 by David’s painting The Distribution of Eagles. Each corps was to be given its own eagle, with a standard on which were to be inscribed on one side the battles in which the corps had participated and on the other the words “Emperor Napoleon to [name of] regiment”.

The weight of the Imperial eagle however was thought to be a handicap: David therefore proposed to lighten them considerably and henceforth to have them made only of gilded sheet metal and flat, instead of in relief and cast in brass. However, the Emperor refused: “the eagle will not change […] The Eagle has to have an imposing quality, whose battles can be cited. That is the advantage of having something that has ‘body’ as an ensign”(Letter to the Duc de Feltre dated 14 January 1812, quoted in Correspondance générale (Thierry LENTZ ed.), t. XII, Fayard, 2012, p. 100 (no. 29743), according to a copy of a dispatch, SHD, département de l’Armée de Terre, 17 C 326). Napoleon reserved the battle honours for the eagle alone: the fanions [smaller flags] were not to include any element, so that, “if by misfortune they were to fall into the hands of the enemy, it would be obvious from their extreme simplicity that they were of no consequence.”(Letter to the Duc de Feltre dated 14 January 1812, quoted in Correspondance générale (Thierry LENTZ ed.), t. XII, Fayard, 2012, p. 100 (no. 29743), according to a copy of a dispatch, SHD, département de l’Armée de Terre, 17 C 326)

The tricolour flag

Between October 1811 and February 1812, there was some discussion about the choice of colours of the flags of the army. For a time, it was envisaged that the tricolour flag, adopted during the Revolution and retained during the Empire, should be replaced by “simpler” colours to be used on a standard which should also bear the inscriptions prescribed by the Emperor. The Minister of War thus proposed a single-colour flag, blue (recalling that white, the colour of the kings of France, was banned and that he did not consider it for a moment). The colours madder red, orange-yellow and grey were also put forward for the Swiss and foreign regiments, for veterans and military crews. The blue-white-red tricolour was finally upheld, as attested by a letter from the Duc de Feltre to the Emperor on 8 February 1812, the latter showing himself to be personally attached to it – and sensitive to the army’s reaction to a change of colours.

Conclusion

David’s spontaneous proposals for new eagles, new arms and new uniforms appear not to have met with the approval of the Emperor, who, visibly annoyed by the Minister of War Administration’s incomprehension of his instructions of 25 December 1811, wrote to the Duc de Feltre, the Minister of War, asking him to take charge of the matter. The Emperor had never wanted the eagles to be meddled with: he wanted “them to make neither eagles nor sticks”, but “only the standards which were to be attached to the eagles.“(Letter to the Duc de Feltre dated 14 January 1812, quoted in Correspondance générale (Thierry LENTZ ed.), t. XII, Fayard, 2012, p. 100 (no. 29743), according to a copy of a dispatch, SHD, département de l’Armée de Terre, 17 C 326)

David’s projects are today preserved in the AF/IV sub-series of the French Archives Nationales, in the section of papers which came from the artillery administration, part of the collection of Secrétairerie d’Etat.

Marie Ranquet, June 2021, (translation Rebecca Young)

Marie Ranquet is Curator of Heritage, responsible for the Executive (1789-1870), Assemblies and State Control archives in the Executive and Legislative Department of the French National Archives

► These drawings can be admired during the exhibition Drawing for Napoleon. Masterpieces of the Imperial State Secretariat, at the National Archives’s Hôtel de Soubise site, which has been extended to 18 October 2021 (but closed from 20 July to 30 August).