A portrait, a reflection of the soul

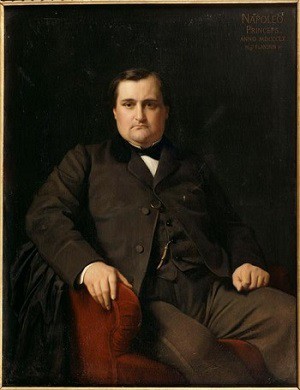

When Hippolyte Flandrin painted this portrait in 1860, Napoleon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte (9 September 1822 – 17 March 1891), better known as Jerome-Napoleon, was 40 years old. Reality is not embellished. The painter has put the subject in a minimalist setting against a plain, dark background. Jerome-Napoleon, Prince Napoleon, wears an unpretentious outfit and is seated on a red velvet armchair, suggesting bourgeois simplicity, far from the imperial purple. These choices enabled Flandrin to draw attention to the face and hands of the Prince, highlighting his resemblance to his illustrious uncle, without hiding the curves of the double-chin or the wrinkles upon the forehead which already showed signs of the passage of time.

Prince Napoleon appears to confront the viewer’s gaze and to demand attention: the portrait does not flatter its subject but rather presents the Prince for what he was. This modest and overtly frank treatment is reminiscent of the Roman busts whose raw realism reflected ancient philosophy: the inevitability of death, the vanity of youth. The Latin inscription at the top right corner “Napoleo / Princeps / Anno MDCCCLX / Flandrin” (Napoleon / Prince / Year 1860 / Flandrin) reinforces this reference to the past. One almost recognises in this Imperial Prince the stoicism and uprightness of an Emperor such as Marcus Aurelius.

The revenge of an artist

Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864) was known for two distinct genres. His religious paintings from the years 1830-1840 were appreciated by contemporaries and decorated many churches, including Saint-Séverin, Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, to mention only those of the capital. But it was for his portraits that he was most famous. According to the majority of critics of the time, Flandrin’s talent stemmed from a particular gift: beyond the faithful representation of the features of his subjects, he succeeded in grasping the expressions and indeed the character of those he painted.

Flandrin was one of the best-known pupils of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Soon after becoming Emperor, Napoleon III commissioned a portrait from Flandrin, probably hoping thereby to establish a ‘family’ link between this work and the famous portrait of Napoleon I on his Imperial throne by Ingres. The Emperor did not seek absolute mimicry between the two paintings but rather wanted to integrate in the portrait his own aspiration to modernity. He is shown standing, bearing no obvious imperial symbol; nor is the rendition overtly stilted: there is a bust of his uncle, Empire-style furniture, an outfit similar to the one he had worn as Prince-President. Here we have an image of the Emperor as a human being. However Napoleon III probably did not realise that he had given Flandrin the means to focus rather too closely on his person. When the portrait was finished in 1861, the Emperor rejected his commission because he considered it too crude: the “sphinx”, to use the expression probably coined by Zola, did not appreciate that the painter had ventured into the protective zone he wished to preserve around himself.

The portrait of Jerome, made the year before, ironically ended up being a kind of revenge for the artist: when it was exhibited in 1861, it met with a resounding success. The Emperor did not want his portrait? Well at least his cousin, who after all was also of imperial blood, knew how to recognise the painter’s talent and accepted his own portrait without hesitation. Flandrin’s ‘victory’ was all the more striking because Napoleon III finally accepted his portrait and allowed it to be exhibited in London in 1862 and then in the Salon of 1863.

Flandrin was not the only one who conveyed a message to Napoleon III in this portrait: the political designs of Prince Napoleon are also displayed in this reply to his cousin.

Jerome-Napoleon was the most rebellious member of the imperial family: “Plon-Plon” (to use his childhood nickname – a deformation of ‘Poleon’) was profoundly secular, liberal and often in opposition to Louis-Napoléon. He was a continual embarrassment to his cousin, later Napoleon III. Jerome-Napoleon was assertively independent, and his positions in contradiction with the official policy of the Empire were often talked about in political circles and in the press. Napoleon III, despite recognising his cousin’s fidelity and attachment to him as a person and to the Bonapartist clan, soon decided it was safer to send the latter on diplomatic missions abroad or to give him the chance for military glory during the Crimean War (1853-1856), comfortably at a distance.

Jerome-Napoleon clearly had designs of one day becoming himself the head of the Imperial family (he was third in line, after his father Jerome, last brother of Napoleon I born in 1784, until the latter’s death in 1860). In the meantime, he champed at the bit, in between each (carefully-measured) challenge to the policy of Napoleon III. The birth, in 1856, of the Prince Imperial, who became the uncontested new heir to the regime, upset his plans. Henceforth, the lucid Prince Napoleon knew that he must resign himself to remaining in the shadow of his little cousin.

The melancholy eyes captured here by Flandrin four years after this birth signals his awareness of this destiny: a final provocation, in 1865, against the authority of the Regent Eugenie and against the policy of Napoleon III regarding the Pope, would entail the disgrace of the Prince. After the fall of the Second Empire in 1870 and the death of Napoleon III in 1873, not even the premature death of the Imperial Prince in 1879 would allow the Prince Napoleon finally to become the heir of the family: before his fateful departure for South Africa, the Prince Imperial had made a will in which he named Victor, Jerome-Napoleon’s own son, as his successor. Prince Napoleon would never reign, nor be recognised as the undisputed leader of the Bonapartist clan.

The writer and journalist-critic Edmond About (1828-1885) summed up the life of Plon-Plon in a premonitory way when he saw Flandrin’s portrait: “Here he is, this decommissioned Caesar”.

After appearing at the Salon of 1863, Flandrin’s painting joined the collections of Princess Mathilde, Jerome-Napoleon’s sister. After her death in 1904, the painting entered the Louvre Museum and later the Musée d’Orsay.

Marie de Bruchard, March 2017 (Translation R. Young)