This painting depicts the attack carried out by the Italian revolutionary Felice Orsini against Napoleon III, and is the work of the little-known Italian painter H. Vittori. It is signed and dated “H. Vittori Romano 1862”.

In the top left-hand quarter of the painting we can see part of the façade of Paris Opera which at the time was located at 12 Rue Le Peletier. It had been built in 1821 to replace the ‘Salle Montansier’ on Rue de Richelieu, which had been razed to the ground by King Louis XVIII in 1820 after Charles-Ferdinand d’Artois (Duc de Berry and the son of the future Charles X) was assassinated there on 13 February of the same year. After it’s reconstruction (and relocation) it became a hot spot for high society, and with the advent of the Second Empire in 1852 it was renamed ‘the Theatre of the Imperial Academy of Music.’(The establishment underwent a number of name changes over the years: Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique (1821–1848), Opéra-Théâtre de la Nation (1848–1850), Théâtre de l’Académie Nationale de Musique (1850–1852), Théâtre de l’Académie Impériale de Musique (1852–1854), Théâtre Impérial de l’Opéra (1854–1870))

On the evening of 14 January 1858, the Emperor and the Empress attended an evening at the Opera. The imperial procession arrived at around 8.30 pm as expected (indeed the fact had been publicly advertised). A carriage bearing officers from the Emperor’s household came first, followed by an escort of lancers of the Imperial Guard, then finally the imperial carriage carrying Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie. The imperial couple were accompanied by General Roguet, a former page of Napoleon I who had become aide-de-camp to Prince-President Louis Napoleon (later Napoleon III). They were on their way to attend a special concert held in honour of the opera singer Eugène Massol on the occasion of his retirement. The attendees expected to hear Marie Stuart, La Muette (written by Massol himself), Guillaume Tell, and the dance from Gustave’s Bal masqué.

Upon their arrival at the main entrance three successive explosions were heard: in front, to the left and underneath the imperial carriage. The glass was blown out of the windows and out of the gas lamps of the Opera building and of neighbouring buildings. The road was peppered with large craters, and injured people were hurled across the street.

The imperial carriage was thrown onto its side by the impact of the bombs, and there were 76 impact marks all over it. Despite the extent of the damage, Napoleon III and Eugenie were unharmed, saved by the iron plates in the floor and walls of their ‘armoured’ carriage. Unfortunately, the same could not be said for their horses; one was killed on the spot and the other was so badly injured that it had to be put down. General Roguet, who had been sitting at the front of the carriage, was hit in the neck by shrapnel from one of the bombs and lost a great deal of blood. Some 156 people (including 21 women, 13 lancers, 11 Paris guards, and 31 Prefecture Police officers) were injured in total, and 8 people died as a result of their injuries (as recorded in an in-depth article about the ‘machines infernales’ (bombs) in the Sunday supplement of the Le Figaro, 19 March 1881). In order to reassure the public of their wellbeing, the imperial couple went on to attend the performance as planned, leaving the theatre at midnight.

The perpetrators were immediately arrested by the police. One of them, a man named Pieri, was arrested on Rue Le Peletier a few minutes before the attack even took place, by a gardien de la Paix (a type of police officer) who had recognised him as a wanted man (and banned from France). He was found to be carrying what is now known as an Orsini bomb (unique at the time for its fulminating detonation method, and so named after Felice Orsini, the head conspirator of the assassination attempt). Pieri was also carrying a pistol, a dagger, and both French and British currency. A man named Gomez was then arrested after being found acting suspiciously in a nearby restaurant. Another accomplice named Da Silva alias Charles De Rudio was arrested later that night after being named by Pieri, and early the next morning a man named Allsop (who claimed to be a British national) was apprehended. The latter turned out to be Orsini himself, a man of Italian origin (from Rome). No difficulty was found in extracting a confession from any of the protagonists; all of them acknowledged their involvement, claiming the attack to be a political act. An investigation concluded that the conspirators had come up with their regicide plot together and had had their bombs built in Britain. All four were indicted on 13 February 1858.

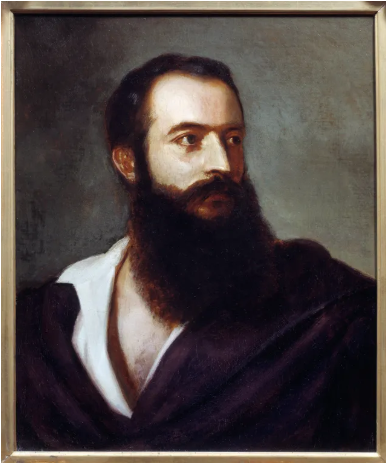

It became clear very quickly that Felice Orsini (1819-1858) was the brains behind the operation. He was a Carbonaro (member of the network of secret Italian revolutionary societies), and a supporter of the unification of Italy under the leadership of the revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini. Orsini was critical of Napoleon III for having betrayed the Italian pro-republican cause (the Emperor had been a supporter of the movement while he was still Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte). The would-be assassin could not stand the fact that the Prince-President had supported the Pope against the Roman Republic in 1849 and in doing so had undermined the republican cause advocated by Garibaldi and defended by the Carbonari.

While awaiting the verdict at their trial Orsini, Pieri and Gomez declined to comment, while Rudio appealed to the court for clemency. After only half an hour of deliberation Orsini, Pieri and Rudio received sentences of capital punishment, as per cases of parricide or regicide according to articles 86, 89, and 506 of the French penal code. Gomez was sentenced to hard labour for life, as was Rudio, finally. None appealed against their sentence. (Click here to read the trial report of Orsini, Rudio, Gomez, Pierri and Bernard. Attack of 14 January 1858… Cour d’assises de la Seine, hearings of 25 and 26 February 1858. [Debates, indictment of Chaix d’Est-Ange, pleadings of Jules Favre. Nogent Saint-Laurent, Nicolet and Mathieu], by Jules Favre, counsel for the accused).

Before his execution, Orsini wrote several letters to Napoleon III, appealing to him to ‘restore to Italy the independence that his children had lost to the French in 1849.’ He continued his efforts in the form of a political vow: ‘May your Majesty remember that the Italians, among whom was my father, shed their blood for Napoleon the Great, wherever it pleased him to lead them; may he remember that, as long as Italy is not independent, the tranquillity of Europe and that of your Majesty will be nothing more than a chimaera: may Your Majesty not deny the ultimate wish of a patriot on the steps of the scaffold; if Your Majesty were to deliver my country, the blessings of 25 million citizens would follow him in posterity.’ [Que votre Majesté se rappelle que les Italiens, au milieu desquels était mon père, ont versé leur sang pour Napoléon le Grand, partout où il lui plut de les conduire ; qu’elle se rappelle que, tant que l’Italie ne sera pas indépendante, la tranquillité de l’Europe et celle de votre Majesté ne seront qu’une chimère : que votre Majesté ne repousse pas le vœu suprême d’un patriote sur les marches de l’échafaud ; qu’elle délivre ma patrie, et les bénédictions de 25 millions de citoyens la suivront dans la postérité.]

Orsini and Pieri were executed on 13 March 1858, at 7 a.m. on Place de la Roquette before a calm and silent crowd of witnesses to “this just and legitimate atonement” (Click here to read the report of Orsini and Pierri’s execution on 13 March 1858).

Did Orsini’s appeal to Napoleon III have a direct influence the Napoleon III’s foreign policy? It is most unlikely. However, a real change in the Emperor’s vision for Europe did occur a few months later when he agreed to meet a leading liberal promoter of Italian unity, the Comte de Cavour, at Plombières on 21 July 1858. On the other hand, the attack did have a number of consequences concerning the Empire. First of all, the Emperor’s personal security was reinforced. A law passed on 27 February 1858 saw an increase in the repression of individuals suspected to be enemies of the Empire, by allowing their extradition (as well as anyone suspected of political crimes after the year 1848). Furthermore, anyone who had not pledged allegiance to Napoleon III was ineligible for election to the Legislative Corps. An Emperor’s Council was set up which would take his place in the event of his sudden death (Napoleon III had become all too aware of the fragility of the regime, should he die prematurely). Finally, General Espinasse, who was renowned for his rigour, replaced Adolphe Billault as head of the Ministry of the Interior and the ministry was (quite eloquently) renamed “ministère de l’Intérieur et de la Sûreté Générale” [‘Ministry of the Interior and of General Security’]…

The Republicans seized this opportunity to draw attention to the despotism of Napoleon III, continuing to do so as late as 1872 when pamphlets telling the ‘true’ story of the plot were still circulating. They portrayed Orsini as a hero and an expiatory victim of the tyrannical regime.

Another consequence of the attack was the Emperor’s decision to build a new opera house. It was to be constructed in an open area with a protected entrance for the imperial carriage. This would be the Opéra Garnier.

Vittori’s painting was acquired by the Musée Carnavalet (History of Paris) in 1892.

Marie de Bruchard, January 2020 (trans. Jessica Rock with Rebecca Young)

![Orsini’s attack [on Napoleon III] outside the Opera, 14 January 1858](https://www.napoleon.org/wp-content/thumbnails/uploads/2020/01/attentat_orsini-tt-width-637-height-390-crop-1-bgcolor-ffffff-lazyload-0.jpg)