This portrait of Jean Lannes (1769-1809), today held at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris, was painted in 1834 by Julie-Louise Volpelière. It was commissioned from the painter for the future Musée d’Histoire de France de Versailles, a project of King Louis-Philippe’s. In this work, Volpelière was in fact copying a portrait made by Baron Gérard. In the same year, 1834, Volpelière, who was a student of Gioacchino Giuseppe Serangeli, painted a portrait of another great figure of the First Empire army, namely, Marshal Jourdan, for the same museum.

Nicknamed “the Ajax of the Grande Armée”, Jean Lannes fought in many battles during the period, from the Revolution to the campaigns of Germany and Austria in 1809 (you can read his biography on napoleon.org). When Volpelière painted her vision of Lannes, more than twenty years after the Marshal’s sudden death, aged forty, on 31 May 1809, Lannes’ reputation was still fresh in people’s minds.

However, Julie-Louise Volpelière’s model by Gérard was itself based (just like that by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, who made another posthumous portrait of the hero) on the only major contemporary portrait of the Marshal known to the public, namely that painted by Jean-Charles Nicaise Perrin between 1805 and 1810. This work had been commissioned by Napoleon I for the Salle des Maréchaux in the Palais des Tuileries in Paris and was presented at the 1810 Salon, the year in which Marshal Lannes’s triumphant burial took place at the Pantheon.

Napoleon wrote to his brother Louis on 24 May 1809: “One loss that was especially significant to me was that of the Duke of Montebello, who had his leg blown off by a cannonball; you know the friendly affection I have for this Marshal; however, he is out of danger” (Correspondance générale, letter n°21060).

Two days earlier, a cannonball had torn Lannes’s leg off during the Battle of Essling. But the Emperor was mistaken, “the Ajax of the Grande Armée” was anything but out of danger: he was to die a week after this letter was written, despite being attended to by Dominique-Jean Larrey, the surgeon of the Grande Armée, doctors from the Emperor’s Household, and Dr Johann Peter Frank, the most famous German doctor of the time.

Upon hearing the news, Napoleon at Ebersdorf wrote to his Minister of Police, Fouché, that he was “very saddened” (Correspondance générale, letter n°21098); he repeated this the same day to Josephine (Correspondance générale, letter n°21105) urging her to console the Duchess of Montebello, the wife of Marshal Lannes. In the meantime, he wrote to the latter: “My dear cousin, the marshal died this morning from the wounds he received on the field of honour. I share your grief. I have lost the most distinguished general of my armies, my comrade-in-arms for sixteen years, the one I considered my best friend. His family and children will always have a special right to my protection. It is to give you my assurance of this that I wanted to write this letter to you, because I am aware that nothing can alleviate the just pain you are experiencing (Correspondance générale, letter n°21106).”

This letter shows Napoleon’s personal attachment to Jean Lannes. He was not the only one. In the collective imagination, Lannes was thought to have been one of the most courageous and loyal of the Emperor’s companions in the Grande Armée. Furthermore, his youth at the time of his death, in addition to his military qualities and bravery, simply served to heighten the hero worship, particularly because of his agony after the Battle of Essling, near the Austrian capital, Vienna, one of the most famous battles of the First Empire.

Politically speaking, it was absolutely in the Emperor’s interests to exalt the idea of the glorious sacrifice made by this great figure in order to prevent the demoralising effect that the news of such a death could have on the troop (and civilian) morale. Thus the account of Lannes’s death was quickly born.

In 1835, Pierre-Narcisse Guérin further exaggerated the legend of Lannes’s heroic end by reinventing the story of his leg amputation and his death, setting these events in the Emperor’s very arms, on the battlefield.

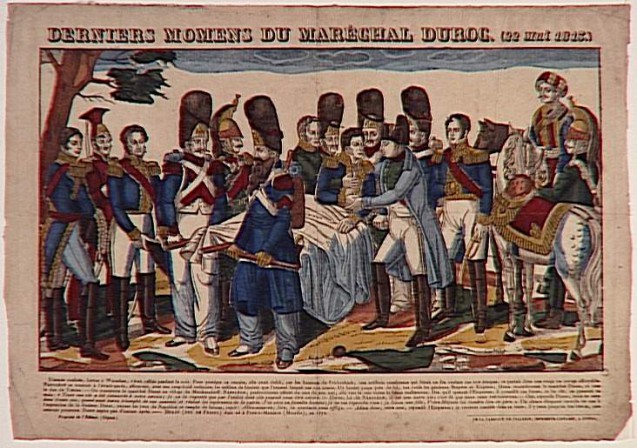

This mythical representation of a farewell between Lannes and Napoleon “in medias res” is not unlike those that circulated after the deaths of other great officers of the Grande Armée. It echoes the death of General Desaix, which occurred after a shot to the chest at the Battle of Marengo in 1800 depicted in 1806 by Jean Broc and also the account of the death General Duroc, which occurred at the Battle of Bautzen in 1813 under the same circumstances as Lannes’s.

The revisitation of Lannes’s demise did not stop with the pro-imperial propaganda’s version or even with the vision imagined during the Romantic period in the 1830s. Just as with the deaths of Desaix, the “righteous sultan”, and of Duroc, the Grand Marshal of the Palace, more or less apocryphal versions of Lannes’s last words and death scene circulated.

In particular, there were reports of some last words spoken by the dying man, bedridden and feverish, to Napoleon at his bedside in the suburbs of Vienna. Lannes is said to have criticised the Emperor for his insatiable ambition and even announced the fall of the Empire… These words are still being debated by specialists in Napoleonic history.

The Marshal’s outstanding courage was however unanimously accepted and raised him to the status of an emblematic figure of Napoleon’s army.

Marie de Bruchard, May 2019 (translation RY)

Find out more: