When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) was at the head of the Prussian state and had been King Wilhelm’s direct right-hand man for over seven years. He had been recalled from his post as ambassador to France in September 1862 to take up the position of Minister President of the Kingdom of Prussia, in which capacity he would also be in charge of foreign affairs. In this role, he was able to realise his political vision of a strong Prussia. Between 1863 and 1865, the kingdom dominated the Polish populations of East Prussia (which it shared with Russia), and also northern territories, which it took from Denmark (with the support of Austria). In 1866, Bismarck provoked the Austrian Empire – Prussia’s age-old rival – into war, and won. In doing so, he made Prussia the leader of the new conglomerate of German states. The creation of the North German Confederation in 1867 was the result of Bismarck’s expansionist strategy.

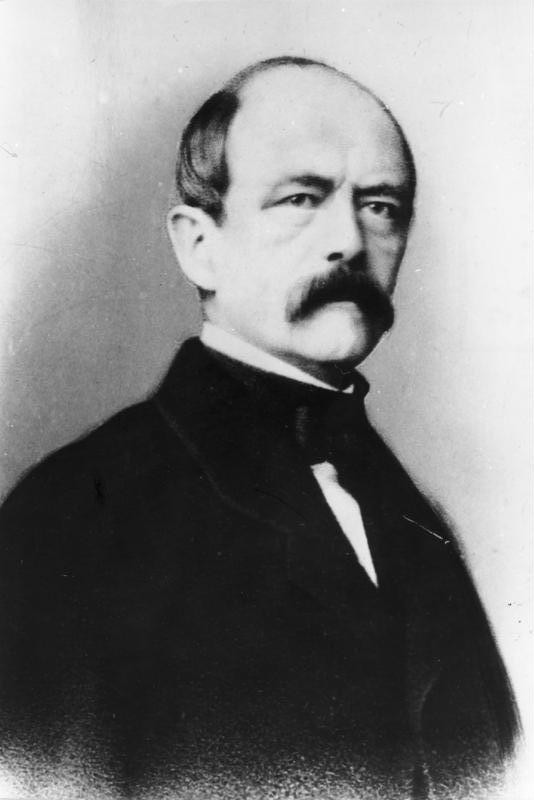

This photo of the Prussian Minister President was taken in 1870, the year that the Franco-Prussian war broke out. By this time, Prussia’s sphere of influence went far beyond the theoretical borders of the Confederation, and the constitution of the latter was a precursor for that of the future federal state of the German Reich created at Versailles in 1871, which came about as a direct consequence of the war with France.

From the civilian to the military: the evolution of Bismarck’s image

During the 1860s, Bismarck was content to be seen in sombre, civilian attire. When he first appeared as a figure on the international stage, he had a reputation for his strict demeanor and was the antithesis of the charm that would have been expected from an ambassador to Napoleon III’s court.

As he was a sophisticated individual with a lively spirit, he did not fit in with the usual caricatures made of Prussians in Paris (they were portrayed as frustrated Junkers [a term for the land-owning nobility] or narrow-minded soldiers), although he was subject to these stereotypes when he first took up his post as ambassador. The French Emperor welcomed Bismarck’s appointment as Minister President in 1862, hoping that it would lead to a warming in Wilhelm I’s attitude towards France.

The charismatic Bismarck rises to power and gains direct influence over Wilhelm I

The new chancellor gained a reputation for his military and diplomatic victories. The 1870s saw a Prussian victory over France (first under Napoleon III and then under the Third Republic) and then the creation of the German Reich, of which Bismarck became chancellor. After this time, the nature of his portraits changed.

He abandoned his sombre, Lutheran black suit for military attire. His new uniform matched that of the King and served as a reminder that it was he who had brought about Prussia’s recent territorial conquests. From then on, he was not officially photographed in anything other than his cuirassier uniform (Bismarck completed his military service as an infantryman ( a Jäger, according to the Prussian military rank). He adopted the cuirassier uniform after he was appointed head of the division in 1866, perhaps in memory of his father, who was a Rittmeister in the Prussian cavalry. After his ‘resignation’ in 1890, he was appointed a colonel general in the cavalry, at marshal grade.) and was also rarely publicly seen in any other dress. This sartorial habit lasted until the end of his career.

His choice of dress was connected to a concern for his personal aesthetic. Bismarck paid a great deal of attention to his taste and had suffered from various illnesses and physical difficulties during the 1870s and 1880s. The uniform served to mask these perceived weaknesses. The Chancellor did not hesitate to crop portraits he did not like and was known to prefer headshots and busts over full-length portraits.

Paintings of Bismarck also showed the control he had over Wilhelm I. For example, here in a watercolour painting by Konrad von Siemenroth, the political duo are depicted in Wilhelm’s chamber at the royal palace in Berlin in 1887, shortly before the Kaiser’s death (he died 9 March 1888). Everything about the painting hints at the dominance Bismarck held over his sovereign: Bismarck is standing upright in his uniform, with an air of seriousness and concentration, and Wilhelm is half seated wearing less pristine attire, looking up at his chancellor with his hands idle at his front. It is as if he is accepting what Bismarck has to say with complete obedience.

Until 1888, Bismarck successfully countered Wilhelm I’s protests about his policies with the various criticisms levelled towards his very personal form of government made by the different political groups in the Reichstag (the government of the German Empire). Conservatives and liberals (Bismarck tried to weaken Catholic political agency, as Catholics did not vote in his favour. He also made sure that socialists were banned from parliament) took turns to ally with him, with varying degrees of success, but they were all often opposed to his unparliamentary vision. Wilhelm I died on 9 March 1888, and after the short-lived reign of Frederick III (which lasted until his death in 15 June 1888), Wilhelm II came to power. After a few stormy months, the new king dismissed the troublesome chancellor.

Bismarck was an essential symbolic figure in the European imagination of the early 20th Century.

Although the majority of the Reich welcomed Bismarck’s dismissal in the hope of some sort of political regeneration, Bismarck’s image did not diminish as a result. His personality was an allegory of the Germany that he had forged over the course of more than thirty years, and this had both international and domestic resonance.

The apotheosis of Bismarck, shown below, was painted when he was dismissed by Wilhelm II. The painting depicts the Chancellor surrounded by figures representing Victory, Germany, and Clio (the Greek muse of History).

The cult of Bismarck was bolstered by his death on 30 July 1898.

In 1901, Ernst Henseler painted one of Bismarck’s last great parliamentary speeches. On 6 February 1888, the Chancellor called for the military reinforcement of the Empire, in the face of external threat. He drew his long address to a close with the now famous words: ‘We Germans fear God, but nothing else in the world!” [Wir Deutschen fürchten Gott, aber sonst nichts in der Welt!].

Few of his contemporaries, and even fewer of his later admirers, remember the rest of this speech. Bismarck linked this call-to-arms with a desire to keep the peace: “And it is the fear of God that lets us love and foster peace.” [Die Gottesfurcht ist es schon, die uns den Frieden lieben und pflegen lässt]. His words were often taken out of context, which led to a misunderstanding.

As the idea of a new European war loomed, in particular a war with France, a myth that painted Otto von Bismarck as a belligerent spread through public opinion. His image was omnipresent throughout the propaganda of the First World War. ( ‘He lives on! ‘ is the title of this portrait by Ludwig Fahrenkrog from 1915)

This myth continued throughout the Second World War, turning Bismarck into a demonic figure in the imagination of the second half of the 20th century. Since then, historiography has allowed us to distinguish between the real Bismarck, and the image that was later created and used to reappropriate the Chancellor to different ends.

Marie de Bruchard, March 2020 trans JR

![Portrait of Otto von Bismarck in 1870 [Photograph]](https://www.napoleon.org/wp-content/thumbnails/uploads/2020/03/450photo_bismarck1870-tt-width-450-height-619-crop-1-bgcolor-ffffff-lazyload-0.jpg)