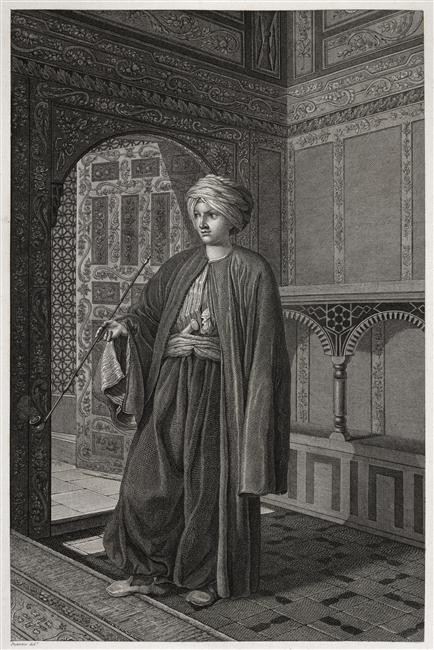

This portrait, attributed to Jacques Nicolas Paillot de Montabert and which remained in Raza Roustam’s possession until his death, was probably commissioned by Roustam himself at the time of his marriage. The painting then went to his son-in-law, who left it to Pierre-Albert Beaufeu, the executor of his will. Beaufeu gave it to the Musée de l’Armée in 1901, where it has remained to this day. Further details regarding the personalised elements in the uniform can be found on the Museum’s website (text in French).

Raza Roustam, an exotic exception amongst Napoleon’s guards

Raza Roustam was born in 1781 or 2 in Tiflis (known today as Tbilisi), capital of Georgia, son of a trader working in Armenia. He was abducted from his family aged either 7 or 13 and then purchased by a Bey from Cairo in whose service he took up as his Mamluk. He was later owned by Sheik El-Becri, who gave him (along with another Mamluk called Ali) to Bonaparte in August 1799. Returning from the Egyptian Campaign, Napoleon took Raza with him to Paris, making him his bodyguard. From this moment on, Roustam would sleep in front of the First Consul’s door. He also became Bonaparte’s valet. In addition to this, from 1802-1806, Roustam was added to the Corps des mamelouks de la Garde.

His firece reputation did not however match reality: Roustam was renowned for his calmness and his debonnaire nature; much appreciated by his master, from whom he would frequently receive presents. For the Coronation, Roustam was dressed in a flamboyantly ‘Oriental’ costume invented specially for the occasion, during which he rode alone in front of the Imperial couple’s carriage. In addition to ceremonial duties, when the Emperor was on campaign, Roustam looked after Napoleon’s meals and made sure his glasses were clean.

On 1 Feburary 1806, the Emperor arranged (and paid for) his marriage to Alexandrine Douville, daughter of Josephine’s “Premier valet de chambre” . The Emperor’s wedding present to the bride was a Lottery Concession.

In 1814, the end of the French Campaign also put an end to the Emperor and Mamluk’s long relationship. When Napoleon tried to commit suicide at the Château de Fontainebleau and asked Roustam for his pistols, the faithful servant took fright and ran off to Paris to join his wife, unlike other Mamluks of the guard who followed Napoleon to Elba. This is probably why Napoleon did not take him back in his service during the Hundred Days (unlike Roustam’s father-in-law, Douville, who had served Napoleon since Egypt). It was Marchand that Napoleon appointed “valet de chambre” in a letter to his Grand Chamberlain Montesquiou, dated 25 March 1815; Douville was made “huissier”.

During the Restoration, Roustam lived on his savings and only returned to a state of semi-grace on the creation of the July Monarchy. King Louis-Philippe gave his wife a job at the Post Office in Dourdan but refused to give the ex-bodyguard a pension. Roustam came up to Paris for the “Retour des Cendres”, adding an element of oriental splendous to the event. He was to die in Dourdan on 7 December 1845.

The Mamluk Tradition

Roustam’s (unjust) reputation for ferocity derived from that of Mamluks in general and which dated from the 13th century when the Sultan of Egypt purchased 12,000 north Caucasian or Circassian slaves. Mamluks were then an elite military caste, led by Beys, and they ended up by taking power in the 15th century over the Arabs and gathering taxes. On the annexation of Egypt by the Ottoman Empire, they came under Ottoman control. Some Mamluks joined the service of General Bonaparte after the siege of Saint-Jean d’Acre.

On 20 June 1800, these men were arranged in two companies called “Horse Janissaries”, which also included Syrians and Copts. They were commanded by indigenous officers, and these companies were very useful, beyond their military and reconnaissance skills, since they could also act as interpreters, the most part speaking Arabic and Turkish.

The sumptuous Turkish-style Mamluk uniforms in the Grande Armée varied according to the wishes of the regimental commanders. However, there was usually a blue turban with a red cap rouge topped with a crescent made of yellow copper, a sky blue jacket with olives, black braids and trimmings, a red waistcoat and a belt with green and red wool knots, red trousers and yellow boots. The Mamluks were armed with a Turkish sword, a espingole (short rifle with a flared barrel), two pistols and an ivory-handled dagger. They also wore a giberne decorated with a yellow copper eagle, suspended from a black polished leather harness. All the weapon and harness fittings of their horses were made of yellow copper, while their saddles were high-handled, with a Turkish backrest and stirrups. In summer, Mamluks wore white canvas pants and a white muslin turban.

The Mamluk companies of the Garde gradually diminished over time as a result of deaths and retirements and, starting in 1809, they began to accept Europeans in their ranks, above all in 1813, when a new reform brought numbers to 250 men. On his return during the Hundred Days, Napoleon decided to break up the Mamluk companies and to distribute the men amongst the regiments of Guard Cavalry. This sounded the death knell for one of the most flamboyant units of the Grande Armée, which influenced not only painting and literature (Lettres d’un mamelouk, written by Joseph Lavallée in 1803) but even women’s and children’s fashions (haircut “à la mamelouke” for grownups and Mamluk uniforms for children).

Marie de Bruchard, March 2019, trans. P.H.

More on Roustam and the Mamluks:

Napoleon’s Mameluke: The Memoirs of Roustam Raza

And other books too , in the Bibliothèque Martial-Lapeyre.