This posthumous portrait of Charles Bonaparte is by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson – more commonly known as Girodet. The artist painted two versions, the first in 1805 (presented in this article) and another version in 1806 (which can be seen here). The two – almost identical – paintings are now held, respectively, at the Château de Versailles and at the Palais Fesch (Fine Arts Museum) in Ajaccio, Corsica.

The father of Napoleon and his siblings had been dead twenty years when Girodet undertook these two works. Charles Bonaparte died of pyloric cancer on 24 February 1785. Exhausted by the constant comings and goings that he had had to make between Corsica and Paris for business reasons (sorting out land and inheritance disputes, as well as organising the placement of his two sons, Joseph and Napoleon), Charles passed away in Montpellier (the French city where he had several acquaintances) with Joseph, his eldest son, beside him.

These numerous financial and family concerns – and the trips he made to try to disentangle them with the relevant authorities – that had become French in 1768 – would explain why Charles, who was from the Italian nobility (a status finally recognised by the Corsican High Council in 1771), had never had time to commission his own portrait, as someone of his now official rank would have done.

Charles Bonaparte died before reaching 39 years of age and did not live to see the sensational rise brought about by the career of his second son, Napoleon.

These portraits thus filled a pictorial void and paid tribute to the pater familias.

It was not only out of filial piety that the new Emperor of the French had these posthumous portraits made in memory of his father.

When he sent the commission to the painter Girodet, Napoleon had recently been crowned and consecrated as Emperor (2 December 1804). He also commissioned a series of grand portraits of himself, regaled in the new symbols of the Empire, from the artist Jacques-Louis David and other fashionable artists, some of them pupils of the latter: namely Gérard, Ingres,… These official commissions (today we would call it an advertising campaign) would only come to an end with the fall of the First Empire: Indeed, throughout Napoleon’s reign, Girodet would be kept busy realising a series of portraits of him.

By commissioning these two portraits of his father in 1805, the new sovereign wanted to lend a certain legitimacy to his new position. By having his father depicted with the finery of the nobility, Napoleon I wanted to insist on his own aristocratic origins. The silk waistcoat and stockings, purple velvet embroidered with gold thread, lace jabot as well as the sword and books were all details “proving” that Napoleon was the son of a learned and high-ranking gentleman.

Furthermore, the choice of posture and background also accentuate this “politico-genealogical” assertion: Charles is shown in a full-length portrait, at a three-quarters angle, standing in front of velvet curtains and a column with an ornate decorative floor made of several types of marble, thus associating him with the high – even the highest – nobility. Even in the details such as the style of the furniture, Girodet subtly reinforces this declaration of the sitter’s noble title: he includes an armchair that clearly evokes – as does Charles’s clothing – the Ancien Régime and the century that had just ended, by the presence of fringes and the shape of its feet (more generally Louis-XV style). Napoleon as Bonaparte was a “self-made-man” a product of the Revolutionary Wars; Napoleon I turned out to be even more so, since he reappropriated the pre-Revolution, including genetically.

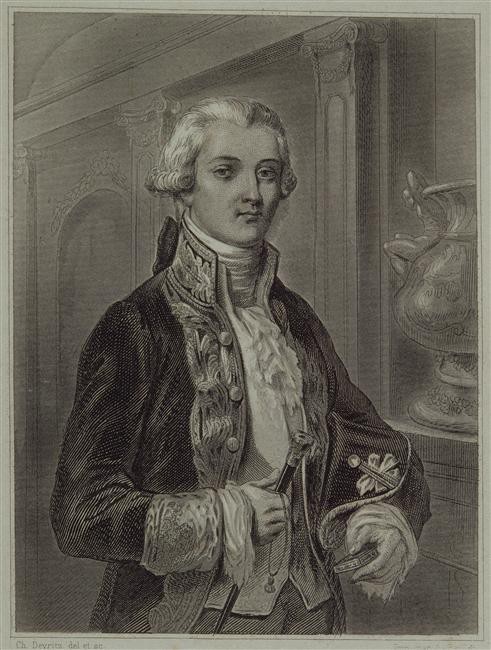

Most other depictions of Charles Bonaparte employ the same pictorial codes as those of 18th-century representations of the nobility, as in the engraving below by Charles Devritz. Two copies of it remain, this one (at the Château de Malmaison), and the other at the Maison Bonaparte (Ajaccio, Corsica).

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée des Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois-Préau) – Gérard Blot

The sculptor Charles-Joseph Marin even went so far as to choose the genre of a bust inspired by Roman antiquity with his marble effigy of the First French Emperor’s father, produced in 1810 (illustrated below). These posthumous representations could even be considered, symbolically at least, as a personal, social, political and aesthetic revenge by the head of the Bonaparte family. It is true that of Charles Bonaparte, whose short life was spent working tirelessly for the recognition of the “gens Bonaparte”, there would be few representations (and all of them posthumous), nevertheless those that were created were to present him the leader of a clan that had become divus.

© RMN-Grand Palais – Gérard Blot

Marie de Bruchard

June 2019 (translation RY and PH)