A promising young engineering officer

Jean-Baptiste Meusnier de La Place (1754-1793), a brilliant scientist of middle class origins, was appointed correspondent to the Académie des sciences at the age of 22 and was elected a member in 1785. There he rubbed shoulders with the greatest scientists of his time (notably Berthollet, Lavoisier, Borda, etc.), and the admiration was mutual. Monge said of him : “He is the most extraordinary intelligence I have ever met”. (« Notice sur le général Meusnier d’après des notes de Monge et d’autres documens également inédits » in Revue rétrospective ou bibliothèque historique contenant des mémoires et documens authentiques inédits et originaux, de Jules Antoine Taschereau, t. IV, 1835.)

Meusnier chose the Military Engineers as the focal point for his talents. After his studies at the Mézières Military Engineering School, he was assigned to fortification work in the port of Cherbourg. Always ready to experiment in order to solve practical problems, he developed a machine to desalinate sea water using vaporisation. He was also responsible for a theorem on the curvature of surfaces, significant advances in descriptive geometry and, with Lavoisier, work on the decomposition of water into oxygen and hydrogen.

The beginnings of aerostatic navigation

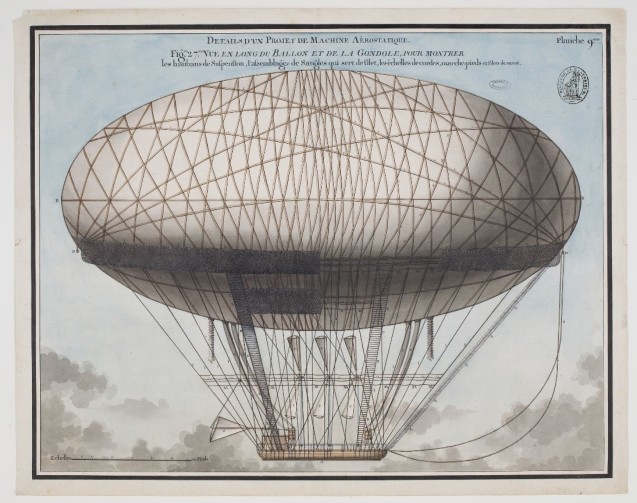

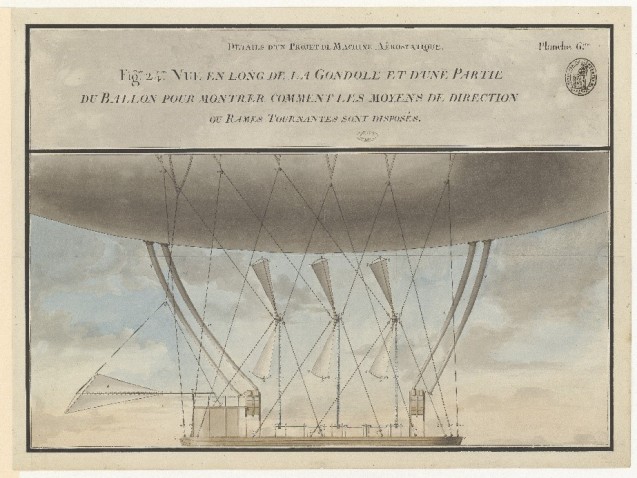

After successful trials with balloons in 1783 (the Montgolfier brothers made an ascension in a hot-air balloon in June, and Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers did the same in a hydrogen-filled balloon in August) the young inventor was inspired. Already in December 1783 (and again in November 1784) he presented to the Académie des Sciences two important memoirs on aerostatic navigation, (The December 1783 memoirs can be read on Gallica: ark:/12148/bpt6k62778899) accompanied by an atlas contenant des dessins et des tableaux relatifs au projet complet de la machine aérostatique (an atlas appendix containing drawings and tables relating to the complete project for the aerostatic machine).(An copy of this atlas can be consulted at the French Archives Nationales shelfmark AF/IV/1955.)

He chose a helical shape for the dirigible because of its aerodynamic properties, and he thought that his design ought to be able to reach the speed of one league per hour. Putting safety first, he designed a gondola capable of floating on the water in case of an emergency landing. One of his major contributions to the science was his use of propellers to give the balloon movement and thus the power to steer independently of the wind (it should be remembered that the use of propellers to propel boats only began in the 19th century and that the patent filed in this regard by Charles Dallery in 1803 was not followed up).

He brilliantly used his scientific acumen to develop a machine to test the strength of the materials used in the construction of his aerostat, in particular the strength and impermeability of the fabrics. The dirigble was designed with two cloth envelopes: the inner envelope contained the ‘flammable air’, i.e., hydrogen – a gas about ten times lighter than air – and the space between the inner and outer envelopes contained the atmospheric air. By introducing more atmospheric air, by means of bellows connected to “windsocks”, the weight of the balloon was increased, allowing it to descend. It was therefore the ambient air that served as ballast.

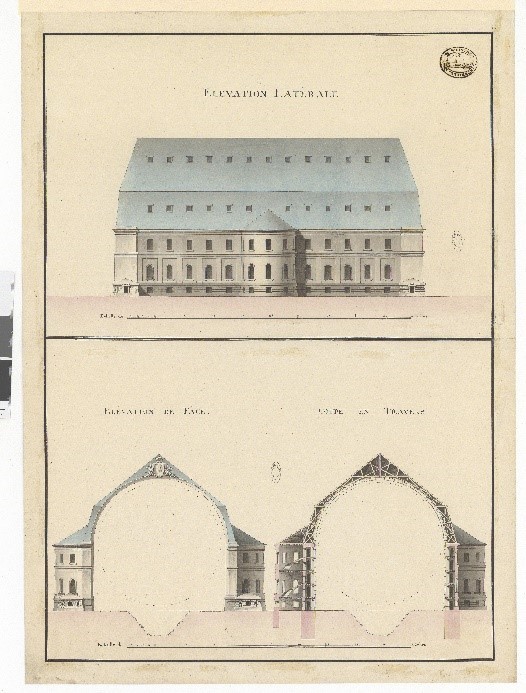

Meusnier’s project was ambitious. A first aerostat was designed to be able to accommodate 30 men with 60 days’ worth of food, and a second was to be for 6 men only and to be used for teaching and experiments. A specific building of gigantic dimensions, comparable to the size of Nôtre-Dame cathedral in Paris, was planned to house the balloons when they were not in use.

An unfinished project

Since he was so busy with military and political business, Meusnier did not find time to write down all the technical explanations that were to have accompanied the plates of his atlas.

On the outbreak of the Revolution, he dived headlong into it with a revolutionary zeal, contributing to the creation and running of the radical Société Patriotique du Luxembourg, quickly becoming its president. However, he continued his inventions by proposing in 1792 a machine for the engraving of assignats, designed to prevent counterfeiting.

He was appointed Colonel and head of a regiment in 1792. Briefly member of the comité des fortifications(Service Historique de la Défense, GR 1VK407.) whose mission was the administration of the Military Engineers, he joined the army of the Rhine in 1793 as a “Maréchal de Camp”. Meusnier de La Place was wounded at the siege of Mainz and died on 13 June 1793.

It seems that his papers that had been left in Cherbourg were sent to the Comité de Salut Public in Brumaire Year III (October 1794). An arrêté dated 4 Pluviôse, Year III (23 January 1795) demanded that they be copied and deposited at the newly created École Aérostatique in Meudon – the originals were to be handed over to the Bibliothèque Nationale. But the Directory, in a decision of 4 Thermidor IV, considered that the content was too militarily sensitive to be accessible to all in a library and imposed the conservation of the originals in the Archives du Directoire.

In 1799, the Comité des fortifications, an institution convinced of the usefulness of the aerostat in war, received from the École Aérostatique in Meudon a collection of drawings by General Meusnier containing the details of his balloon project for a long-distance voyage (including a memorandum and a cost estimate).

Napoleon and aerostats

Napoleon was not indifferent to the possibilities offered by aerostatic navigation, as the presence of Meusnier de La Place’s album in the Imperial State Secretariat Archives attests. In 1796, during the blockade of Mantua, he asked for the intervention of one of the brand new Companies of Balloonists. (The first company was founded in April 1794, the second in June.) When he left for Egypt in 1798, he took with him Captain Lhomond’s Company of Balloonists and all the equipment that this implied. But in the end the balloons had no military use and the public demonstrations for propaganda purposes did not have the expected effect on the population of Cairo.

The Directory decided to disband the Balloonist Corps in February 1799. Nor did Bonaparte envisage its re-establishment, the slowness of the aerostats coinciding badly with the swiftness of his military tactics. On becoming emperor, Napoleon was content to take the advice of specialists in this regard: in 1808, Gaspard Monge advised him against following up on a project, submitted by Lhomond, to invade England with 100 aerostats which he (Monge) considered too unrealistic.

Whilst the military use of aerostats was quickly abandoned, balloons however nevertheless had a strong symbolic potential(The rising up into the heavens was seen as sort of transcendental) that was perfectly suited to large public ceremonies. In 1804, during the coronation celebrations, Jacques Garnerin’s immense balloon, decorated with an eagle and three thousand coloured pieces of glass shimmering in the air, set off, to the applause of the crowd, towards Rome, where it arrived the next day.(This balloon still survives and is currently held at the Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare di Vigna di Valle http://www.aeronautica.difesa.it/storia/museostorico/Pagine/IlPallonediGarnerin.aspx (text in Italian)) For the wedding of Napoleon and Marie-Louise in 1810, Sophie Blanchard, one of the first female aeronauts, with a balloon magnificently “adorned with ingenious emblems and allegorical paintings”, as reported in the Moniteur Universel of 27 June 1810,(https://www.retronews.fr/journal/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universel/27-juin-1810/149/1331847/2 (text in French)) rose into the air throwing flowers and greeting the newlyweds. For the birth of the King of Rome the following year, another equally impressive public ascent was organised.

As for Meusnier de La Place’s invention, it was soon forgotten before inspiring the inventors of airships. His work seems to have been known to Henri Dupuy de Lôme, who developed a propeller-driven dirigible in 1870 at the request of the National Defence government.(L’aérostat à hélice, construit pour le compte de l’État, sur les plans et sous la direction de M. Dupuy De Lôme, 1872.) In 1886, Meusnier’s work was presented again to the Académie des Sciences,(Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des sciences / publiés… par MM. les secrétaires perpétuels, July 1886.) with a photographic reproduction of his album, this time by Colonel Perrier who praised Meusnier’s status as precursor. Meusnier was from then on to be considered as one of the pioneers of aeronautics.

Aude Roelly (English translation PH)

March 2021

Aude Roelly is an archivist paleographer and Conservateur général du patrimoine. She is in charge of the Département de l’Exécutif et du Législatif at the Archives nationales.

This work is part of the exhibition Drawing for Napoleon (Archives Nationales, Paris, 10 March – 19 July 2021) for which a maquette of this aerostat was realised with the financial support of the Maison Chaumet.