The night of 2 June 1849, 30,000 soldiers under the command of General Oudinot attacked the fortifications on the Janiculum hill. It would be another month before the French expeditionary corps – greater in number, arms and equipment – would succeed in entering Rome. The city had been declared a Republic in February after the abolition of the pope’s temporal power, and the supreme pontiff had subsequently sought refuge at the court of the Bourbon king in Naples. In a polar opposite of the operation led by General Berthier in 1798 – which resulted in the creation of the short-lived Sister Republic – the army of the Second French Republic arrived in Rome to restore the pope as ruler of the Papal States. In the face of a French siege and bombardment, the defence of Rome was to prove fierce but ultimately hopeless, despite a few initial successes – more the result of the French leadership’s underestimation of the city’s capabilities than anything else. Indeed, Garibaldi’s memoirs describe a failed French assault, which took place on 30 April:

“The enemy general’s tactics showed nothing but contempt for us […] Faced with routing [what he thought were] a few Italian brigands, General Oudinot – this offspring of a First Empire maréchal – saw no need to consult a map of Rome. But he soon realised that we were men who were defending [our] own city, facing mercenaries who were Republican in name only.”

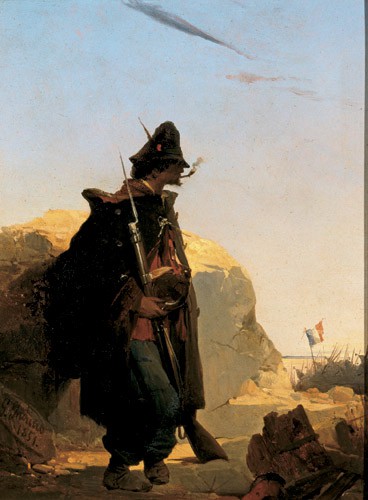

Amongst those serving under the Condottiere was Gerolamo Induno, a young painter from Milan who participated in the anti-Austrian insurrection that had broken out in the Lombard capital in March 1848. Were it not for the red tunic identifying the watchman as one of Garibaldi’s legionnaires, the picturesque painting could quite easily be a depiction of a simple peasant from the Abruzzi. The soldier in the painting stares out impassively at the French flag floating above the phalanxes of what Garibaldi bitterly called “Cardinal Oudinot’s warrior-monks” (letter from Garibaldi to Anita, 12 June 1849). His apparent detachment coupled with the slightly ironic poise and jaunty pipe imply that this painting could be something of a self-portrait. The painting is one of the most poignant accounts of the fratricidal struggle produced by the artist, who was badly wounded at the Battle of Vascello. The conflict also served as material for his compatriot Stefano Lecchi, author of the first known photographic war report in history, and the French photographer Frédéric Flachéron. The subsequent occupation of Rome by French forces clearly demonstrates the complexity of the issues at stake for the Prince-President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. The pope was restored to Rome, his temporal power guaranteed by a French garrison, but these early stirrings of Italian nationalism would eventually win Napoleon III’s support as the emperor pursued an at times paradoxical policy towards Italian affairs.

Sylvie Leray-Burimi (tr. & ed. H.D.W.)

Curator, head of the iconography department, Musée de l’Armée

Curator, “Napoléon III et l’Italie, Naissance d’une nation, 1848-1870”

December 2011