- Napoleon.org: What is the INPS and its laboratory in Marseilles? In brief, who are you?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: The Institut National de Police Scientifique (INPS) [the French National Institute of Forensic Police] is an administrative public body under the jurisdiction of the French Minister of the Interior. It is the most important public body in France for criminal analysis. The institute covers the majority of aspects related to criminal analysis, with faculties in genetics (nuclear and mitochondrial DNA), fingerprint technology, document and handwriting analysis, ballistic analysis, lesion studies, gunshot residue analysis, narcotics, toxicology (in the areas of forensics and road safety), fires and explosions, and micro-traces. The INPS employs 850 officers distributed amongst 5 laboratories (Lille, Lyons, Marseilles, Paris et Toulouse) and a central administration centre (Lyons). The establishment works on both domestic and international projects, one of the most notable being the development of facial composite technology.

The Marseilles laboratory was created in 1927, and it has 150 officers including 40 experts. It mostly operates within its natural geographic area, covering the Mediterranean basin and the bordering départements (including Corsica), but, like the other laboratories, it has a responsibility to take part in investigations from all over French territory. It therefore responds to requests from police investigators, from the National Gendarmerie, and from magistrates.

It has specialist expertise on everything relating to the characterisation of ancient DNA, but also in matters of diatomic research, forensic entomology, and toxicological hair analysis in date-rape drug cases. The laboratory is also a leader in the field of gunshot residue research.

Note that its activity in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and in fingerprint research are covered by COFRAC accreditations in accordance with standard ISO17025. The research areas of gunshot residue and road-safety toxicology are in the process of accreditation.

In 2019, almost 20,000 tort and criminal files representing 45,000 analysed judicial seals were processed by the laboratory.

- Napoleon.org: What is the path to becoming the head of a forensic laboratory?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles : The managing officers of forensic laboratories come from either a) from amongst the corps of engineers from the technical and scientific branch of the police, who are recruited through a competitive examination process overseen by the Ministry of the Interior, or b) from amongst the senior management of other administrations.

The directors and their assistants are seconded to functional posts, regulated by decree 2013-1135 of 9 December 2013.

The heads of the laboratory units are technical and scientific police engineers. Their training – at engineering schools or universities – covers scientific disciplines representative of the forensic fields (for example genetic biology, analytical chemistry, toxicology, physics, computer science, signal processing, ballistics…).

The experts working in the laboratories are officers who have been designated according to their experience, technicality, and high-level knowledge. Their abilities are subject to ongoing assessment.

- Napoleon.org: Is there a difference between the scientific expertise used in ‘historical’ cases and that used in ‘judicial’ cases?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: There is no difference between the technical approaches taken in both areas of expertise. Both areas of expertise require the same working conditions, the same follow-up report, the same necessary precautions to be taken, as well as the same routine analytical methods to be used.

From the creation of the ‘ossements’ (bones) team in 2003, the methods of ancient DNA analysis developed during the university career of A. STEVANOVITCH (doctor of immunology-biology specialising on ‘the study of mitochondrial DNA in the ancient and existing populations of the Mediterranean,’ notably the population of the archaeological site of Taforalt in Morocco dating back 12,000 years) have been faithfully implemented in their forensic approach. Over time, with technical development, these methods were then improved and optimized, and the team has therefore stayed at the forefront of its field (as observed by the scientific congress, in which the INPS actively participates).

Routine laboratory methods are therefore perfectly adapted to the most sensitive of cases, giving a close to 100% success rate in ‘judicial’ cases and complete effectivness in ‘historical’ ones.

The difference between the two areas of expertise is therefore exclusively judicial: cases referred from the Police/Gendarmerie or tribunals are purely judicial, and cases of identification of unidentified deceased historical characters (decree of 2012 relating to extra-judicial procedures) are extra-judicial.

Judicial cases and historical cases share the same constraints: small quantities of material to study, a media environment, and the need for sample conservation and absolute reliability. It is true that we are proud of our identification of historical persons, but that being said the identification of unknown individuals on a day-to-day basis is just as rewarding since the long-awaited results are emotionally charged and important for their families, whether known or not. These identifications are always a way of writing the end of a chapter, whether in history with a big H or simply in the story of a family.

- Napoleon.org: People talk about mitochondrial DNA as opposed to DNA on its own… what is the difference?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: In a cell, there are two types of DNA: nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA. Nuclear DNA is the best known, and it is the one that’s passed on to children jointly from the father and the mother in the form of the chromosomes present in the nucleus of a cell. With the exception of identical twins, this DNA is unique to each individual. For direct parentage studies (the line from parent to child), the nuclear DNA allows the identification of an individual with a very high final probability (well above 99.9999%).

Mitochondrial DNA is a small, circular DNA on the outside of the nucleus, found in cellular organelles called ‘mitochondria’ (which serve as a powerhouse for the cells), giving it its name. This DNA is found in large numbers in each cell (around 10,000 copies, in contrast to nuclear DNA which only has 2 to each cell) and is only passed on to offspring from the mother. It has less selective power than nuclear DNA (it identifies the maternal line, and not individuals), but it can prove useful for identifying familial links that cannot be reliably evaluated through nuclear DNA (for example siblings, nephews, grandchildren etc.). Furthermore, the high number of cellular copies makes it possible to obtain results in cases where the nuclear DNA has completely degraded.

In the case of the ‘General GUDIN’ file, the laboratory team worked with both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Analysis of the nuclear DNA confirmed, with extremely high probability, links between the bones found in Russia and the father, mother, and son of General Gudin. Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA confirmed the link between the bones and the mother and brother of the general.

It was therefore the combination of the two types of DNA that made it possible to make a complete familial link between the bones discovered in Smolensk and those interred in the Gudin family vault in Loiret.

bust by Louis-Denis Caillouette © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Franck Raux (website https://art.rmngp.fr)

- Napoleon.org: What other historical cases have called upon your analytical services?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: The team has had the opportunity to work on several historical files over the past 15 years, notably:

– The analysis of two skeletons that were discovered in a memoria (an object of veneration) during the archaeological excavations of a 5th-Century church on Rue Malaval in Marseilles. The mitochondrial DNA of one of the two skeletons was characterised, but the state of conservation of the second was such that it was not possible to draw a comparison (the skeleton was found in an extremely degraded state in very humid conditions) or to establish a link of filiation between the two. To date the skeletons have not been identified, and are on display at the Marseilles History Museum.

– The analysis and comparison of three relic bones preserved in different churches in Lyons and thought to belong to Saint Irenaeus. A C14 dating (carried out by another laboratory) excluded 2 of the 3 relics from being contemporary to Saint Irenaeus, but a mitochondrial genetic profile was obtained for the relic dating from the 2nd century meaning it could therefore potentially belong to the saint.

– The identification of a number of combatants from the Second World War:

• Solider Lawrence Gordon (a Canadian solider, enlisted in the American army, killed in Normandy in 1944 and buried erroneously in a German cemetery).

• Prince Alexis Fürst von Bentheim und Steinfurt (a German pilot shot down in 1943, whose skeleton was discovered on an island off the coast of Marseilles, and was initially believed to be that of a pirate from the Middle Ages).

• Georges Coran (a member of the French Resistance, shot by the Gestapo in 1944 and not identified at the time). His remains were buried at the National Necropolis of the Doua in Lyons and were identified by a similar strategy to that used in the case of General Gudin. In the absence of any compatible descendants, it was necessary to exhume the bodies of the individual’s mother and sister for comparison.

–The identification of a combatant of the First World War:

• Charles Lavocat (a “poilu” [a French First World War infantryman] killed in 1914 whose remains were exhumed during the excavation of a temporary military cemetery, rediscovered while road works were being carried out).

- Napoleon.org: Did you encounter any particular difficulties during the identification of Gudin (for example acidic soil, etc.)?

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: The main difficulty encountered during this case was caused by the state of conservation of his bones. The 207-year-old bones came from Smolensk and were very brittle and dry, and proved to be a real technical challenge for the team, in particular when removing a sufficient amount of material (which is necessary for analysis) without compromising its support. The tooth used for analysis did not pose any particular difficulties, except for its small size and the small amount of material present.

For the family members (used for comparison) exhumed in Loiret, the difficulty came from cleaning the bicentennial bones which were, in contrast to those found in Russia, humid and completely covered in earth (keeping in mind that to conserve the maximum amount of DNA, it is preferable not to wash bones in water). In this case, the laboratory team decided first to dry the bones, and then to scrape them meticulously to remove the soil while they were amalgamated on supports, taking care not to damage them. This proved to be a wise technical decision.

- Napoleon.org: In the Gudin case, why were contemporary remains chosen over his descendants? Was anything lost?

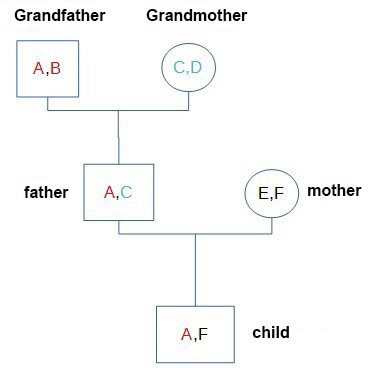

INPS Laboratory of Marseilles: Genetically speaking, for each generation only 50% of a parent’s nuclear DNA is passed on to their child. So, the grandson of an individual only has 25% of the DNA of their grandparents at most. In the example shown below, the child only has one character in common with their grandfather and none with their grandmother. The more generations are added, the more the genetic heritage is diluted. From a statistical point of view, from the 2nd generation on it becomes very complicated to obtain probabilities that would allow the formal identification on the sole basis of nuclear DNA.

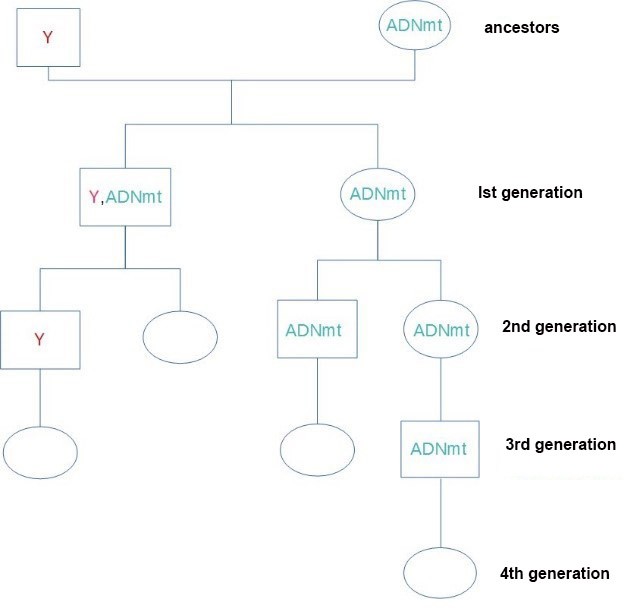

With regard to lineage markers (either maternal through the mitochondrial DNA or paternal through the Y-chromosome line), direct transmissions of the same character between each generation can be traced over many generations. However, these genetic lines must be present continuously from the ancestors to be usable (see the example below where the maternal and paternal lines are interrupted in the 4th and 3rd generations respectively).

Therefore, according to the preceding explanatory diagrams, the living descendent of General Gudin is too far removed from the genetic heritage of their ancestor for a study of nuclear DNA, and also belongs to different maternal and paternal lines, which means they would not be suitable for an informative comparison. The contemporary remains of his direct relatives (his father, mother, brother, and son) were more suitable for formal identification.

Learn more about the 2019 excavation to recover General Gudin