- Napoleon.org – Can the OCBC be accurately summed up as the office that deals with the recovery of stolen art and historical artifacts?

Jean-Luc Boyer – The OCBC (in French) is a specialist department of the Judicial Police. They deal with every aspect of cultural property trafficking, that is, theft, concealment, fraud, money laundering, and counterfeiting. The OCBC is made up of members of the gendarmerie and the police force. At the moment, the head of the department is Didier Berger, who is a colonel in the gendarmerie, and I am a police commander.

- Napoleon.org – Can you tell us about the history of the department?

Jean-Luc Boyer – It was created in 1975, as part of the Direction Centrale de la Police Judiciaire (DCPJ) [the Central Directorate of the Judicial Police]. At the time of its creation, Italy and France were subject to more thefts than any other European countries. Throughout the 80s and 90s France saw a period of church looting (these were the principal targets along side the châteaux and some carefully targeted private houses). So these two countries created their own respective departments to deal with the trafficking of cultural property. Alongside its Italian counterpart, the OCBC is internationally held to be a leader in the field. We were also the first to create their own databases: The photographic database TREIMA (Thesaurus de Recherche Électronique et d’Imagerie en Matière Artistique [Thesaurus for Electronic Research and Imaging in the Arts] and the LEONARDO Database in Italy (which has 600,000 documented objects with images).

Today, there are twenty five people working at the OCBC (including 15 investigators) and they cover the whole of France. It is true that that this is not much considering the geographic area covered and the volume of objects to be processed. Just to show by comparison, there are three hundred Italian carabinieri [the Italian gendarmerie] working in an equivalent department. But that being said, it hasn’t prevented the French team from achieving an international reputation.

- Napoleon.org – What does your work consist of, in real terms?

Jean-Luc Boyer – It ranges from the mastering of a set of very specific laws (for example, passports are required to move cultural items within Europe), and together with the judicial customs and the gendarmerie we have a joint power-of-seizure of stolen artefacts (a permanent customs representative works in the department). Unlike for example drugs trafficking, cultural property trafficking is done for exportation: objects are stolen with the intention of moving them abroad.

Until the 2000s, there were 15,000 thefts in France per year: the department was founded to deal with this, and to dismantle the supply chains. Typically, during these years, the stolen goods were very quickly put onto what was, at the time, a very dynamic market. The thieves would break in during the night, and head for the border in the early hours to cross over into Belgium, where they would immediately find a black market dealer, resell the stolen objects, before returning to France.

It is important to note that the legislation differs between France and Belgium: in France, there is no statute of limitations for the handling of stolen goods, whereas in Belgium the statute of limitations is five years from the time of the theft. Geographically Belgium, then the Netherlands and Germany are the crossroads of the European market, and from these countries the goods can be easily sold on to the United Kingdom, the United States, and the rest of the world. Outside of Belgium, another large operation was that of the Sicilian network. They would pick and choose objects in the villas and museums along the Côte d’Azur, steal them, and then import them to Italy. Once they reached Sicily, they would be put on the market (via the free economic zones, in Switzerland for example). During the 1990s, we caught three or four big handlers of stolen goods, and this put an immediate stop to the chain of operation: a handler creates demand and supports two or three teams of specialised burglars. The theft statistics for 2019 showed fewer than 2,000 per year.

- Napoleon.org -What is a handler of stolen goods?

Jean-Luc Boyer – Someone who handles items in bad faith. Someone who, for example, goes abroad to an antiques market, buys an object, and returns to France with a receipt of purchase is not considered a handler of stolen goods: that person can prove that they bought the object, and the purchase can be traced. That person is considered to have purchased the object in good faith. The minimum sentence for the theft is three year imprisonment, and for the “handling of stolen goods” it is five years.

- Napoleon.org – Does your work include theft prevention?

Jean-Luc Boyer – The prevention of the theft of cultural property is not one of the principle missions of the OCBC: that is a completely different job. It is carried out by police officers with a specialised qualification (référent sûreté [security advisor]), who are seconded to the French Ministry of Culture. They are responsible for carrying out audits in situ to evaluate how public environments can be secured (this includes national museums, or private museums if they have items belonging to the state in their collection, and also churches).

- Napoleon.org – The responsibilities mentioned so far (theft prevention and investigation after theft) concern French cultural property. What about stolen cultural property belonging to foreign states found in French territory?

Jean-Luc Boyer – Whether the object is French or not, once it is discovered in French territory it is within the remit of the OCBC on the principle of handling of stolen goods.

- Napoleon.org – The online databases, some of which are available to everyone, have been the ‘novelty’ of the past twenty years, but are they effective?

Jean-Luc Boyer – The databases explain the dramatic drop in thefts we’ve seen over the period. The act of theft itself is not the complicated part; it’s the resale of objects that has become more difficult, thanks to the databases. The TREIMA database dates from 1994-95, and contains the photos of both public and private objects, stolen from this time onwards. After a complaint is filed after a theft, we need a photograph of the object to enter it into the database: we cannot find an object based on a description alone. This makes working on archaeological thefts very complicated.

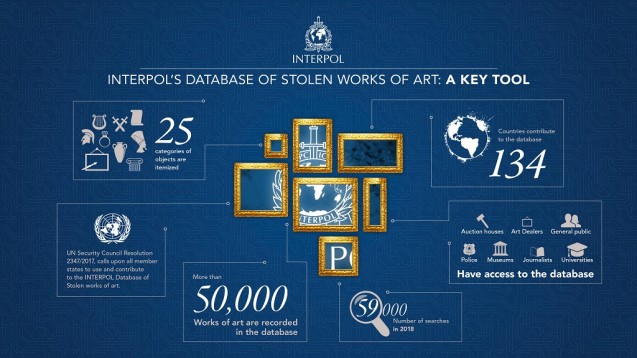

If the object is a prestigious one, and clearly identifiable, our department – as with all the equivalent departments in other countries – will forward it to Interpol’s PSYCHE Database (Protection System for Cultural Heritage)

The TREIMA database is only accessible to the police, the gendarmerie, the customs, and certain individuals at the Ministry of Culture, but the PSYCHE database is open to public access [ed: after creating an account]. The major players in the art market (for example Sotheby’s, Christies, Artcurial, and also mainstream antiques dealers) rely on this tool to verify, through a private third party, that the objects they have up for sale are not in the Interpol database.

For its part, the Ministry of Culture has done a lot of work toward theft prevention with its Palissy database, which it uses to itemise, locate, and photograph objects of cultural heritage found in public places, for example churches (this systematic cataloguing was almost non-existent in the 1980s), museums, town halls, etc.

- Napoleon.org – Who developed the TREIMA database?

Jean-Luc Boyer – The database works on the same principle as the thesaurus, which allows you to search using keywords. In 2000, we added a image-to-image recognition, which required the input of specialist engineers. The OCBC was the first to put this system in place. This update was managed by another specialist unit, under the direction of the Service des Technologies et des Systèmes d’Information de la Sécurité Intérieure — ST(SI)2 [the National Security Technology and Information Systems Division], which is responsible for everything to do with software, databases, recognition systems, etc.

- Napoleon.org – Is there a specific educational path you need to follow if you want to work for the OCBC?

Jean-Luc Boyer – A qualification in History of Art is not required – although it’s an added bonus if a candidate for the OCBC has a certain affinity with the subject – but above all we look for, and need, people who have a perfect command of their working tool: that is to say, the code of criminal procedure.

- Napoleon.org – There are lots of collectors amongst the history enthusiasts (not just of Napoleon) who follow us. Can they contact you if they are ever in doubt about an antique they have found online?

Jean-Luc Boyer -Of course. They can contact us at sirasco-ocbc@interieur.gouv.fr [ed. The SIRASCO is another branch working under the Central Directorate of the Judicial Police: they are responsible for information and intelligence related to organised crime, as well as its strategic analysis] and we will process their query.

We can only advise caution when it comes to buying antiques and cultural objects: never make purchases in cash, without a sale receipt.

© RMN-Grand Palais (Palace of Fontainebleau) / Gérard Blot

- Napoleon.org – Were you keeping a closer eye on the Musée Chinois after the theft of 2015?

Jean-Luc Boyer – It’s obviously physically impossible to reinforce every place that’s been a target of theft. We have developed and internet surveillance within the OCBC and with the other gendarmes who have access to the TREIMA database. At the OCBC, we have three people who, as well as their other numerous tasks, spend part of their time keeping an eye on the market and its trends. This is like casting a single fishing line into the ocean when what you actually need is many, enormous trawlers. You need to understood that we would ideally require several dozen people to participate in this surveillance, but we can’t afford it. In this context, when a major theft like the one at Fontainebleau has taken place, we look to see if the objects appear on the internet. We aren’t the only ones: the carabinieri do it too. There is also private company called the The Art Loss Register that exclusively uses this method, and works for professionals. It employs between forty and fifty people to carry out these sorts of online searches on a daily basis, as well as searches in sales catalogues. The OCBC is immediately informed if they find something that was stolen from Fontainebleau in 2015. As was reported in the press, the attempted robbery of the Musée Chinois at the end of 2019 was thwarted thanks to information passed on from our counterparts abroad [ed. the Judicial Police of Madrid] who’d caught wind of it. Inversely, it often happens that, while working on a certain theft gang, we discover their plans to carry out a robbery abroad. Obviously, we then inform our counterparts in the relevant country.

© French Customs – Patrice Pontié. Source : 20minutes.fr

- Napoleon.org – In what way do you work with cultural and academic institutions?

Jean-Luc Boyer – As I said before, the problem with objects taken from archaeological sites is the lack of photos. Instead we work with the typologies of objects. The ICOM (International Council of Museums) created the Red Lists with this aim. To use these lists we need experts, particularly when the objects concerned come from civilisations spread over a vast geographical area such as antiques from the Roman Empire for example, which could come from anywhere in Europe, even territories that are currently war zones, such as Libya and Syria. We also need to work with experts who can identify the geographical area, period, or even indeed precisely the site an object comes from and tell us whether there has been any known looting there. At the moment, following the example of the CNRS (French National Centre for Scientific Research), we are increasing our connections with these university specialists, who have little or no involvement in the market but a high level of expertise [ed. another example is the interview (in French) with the current director of the Laboratory of Hellenisation and Romanisation in the Ancient World at the University of Poitiers].

- Napoleon.org – And with UNESCO ?

Jean-Luc Boyer – We work with UNESCO to the extent that the organisation publishes conventions that each signatory country is supposed to apply. For example, the convention of 1970 includes a paragraph indicating that signatory countries must create a specialist force dedicated to the fight against the trafficking of cultural property. It must be noted that not all signatory countries have done so (learn more – PDF in English). They also publish recommendations concerning cultural property which each state can transform into legislation at its own discretion.

A short while ago, we noticed that there was a serious loophole in the import crime legislation that had not existed before 2016. After the 2015 attacks in Paris, it came to light that terrorism was potentially being funded by the looting of archaeological sites. This prompted the development of a legal framework in France [ed. Learn more about these legal provisions at the French level (in French – also see the extra reading material below), and at the European and international level].

- Napoleon.org – Is the document [in French, dated October 2010, cover shown above] presented on the website of the Ministry of Culture up to date?

Jean-Luc Boyer – Yes, perfectly. The Ministry of Culture developed these recommendations hand in hand with the OCBC. It is quite interesting and important in the context of theft prevention. The information we get from small town halls or small museums is essential. The fact is, in times past, these places didn’t necessarily think about taking photos of their cultural property, or filing reports when they noticed they were missing. It is important that they do so, regardless to lack of accuracy as to when they checked and or when they actually lost the object. Of course, there is a statute of limitations for theft or concealment, but that’s not the case with civil law: public goods are inalienable, that is to say that there is no statute of limitations for the state in recovering its artistic works once photographs have been entered into the database (hence the importance of reporting thefts), and regardless of when they resurface in French territory.

The above document is there for public institutions, but it is just as useful for private collectors to help them as much as possible to prevent thefts, and also to know how best to act after a theft in order to increase the chances of the recovering the cultural property.

- Napoleon.org – Do you ever work on recovering cultural property looted during the Second World War?

Jean-Luc Boyer – After the war, it was the Foreign Office that tried to manage that with Germany. Today, the OCBC does not often deal with these cases, which can be explained by the criminal statute of limitations, which directly concerns the OCBC’s missions. In cases of handling of stolen goods, where the individual is a first owner and has the item in good faith, there is a statute of limitations of six years. Therefore, with objects taken during the Second World War, there is a 99% chance that the current holder would be acting in good faith.

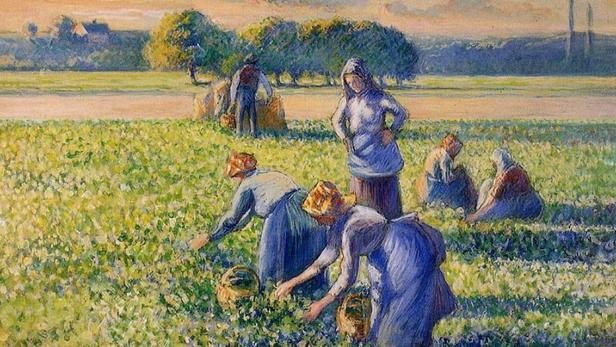

It’s different for civil cases: the order of 21 April 1945 [ed. which was added to an earlier order of 12 November 1943], clearly states that all forced sales operations and all robberies of cultural objects carried out under the Vichy regime are void. When cultural property is found in France, it has to be returned. We have the recent example of a painting that was on display at the Musée Marmottan in France, ‘La cueillette des pois’ [the Pea Harvest], which was on loan from an American family in good faith but had originally been stolen from a French Jewish family during the war. The painting in question will be returned to the French family’s descendants.

Further reading:

Information about the OCBC [in French] – Châteaux, musées pillés… LES FLICS DE L’ART SONT LÀ [Châteaux, looted museums… THE ART COPS ARE HERE]

The thwarted robbery of the Musée Chinois in December 2019 [in French] – Tentative de cambriolage du musée chinois du château de Fontainebleau: six malfaiteurs mis en examen [The attempted burglary of the Musée Chinois at the Château de Fontainebleau: six criminals indicted]

The robbery of the Musée Chinois in 2015 [in French] – Important vol d’œuvres d’art au musée chinois de Fontainebleau [Major theft of artwork at the Musée Chinois at Fontainebleau]

Information on private law – The law concerning stolen cultural property

Presentation on Interpol’s PSYCHE database

More about stolen property and its restitution:

- Restitution des biens culturels – Audition de M. Jacques Sallois, ancien président de la Commission scientifique nationale des collections [The restitution of cultural property – The hearing of Jacques Sallois, former President of the National Scientific Commission on Collections – in French]

- About the Commission for the Compensation of Victims of Spoliation (CIVS)

- Nouvelle compétence de cette commission depuis 2018 : recommander la restitution des spoliations [New powers at the CIVS since 2018: the recommendation that artwork is returned – in French]