-

Introduction

We invite you to take a trip through the Ile-de-France and Haute-Normandie, to rediscover some of the greatest French writers of the 19th Century. Not meant so much an overview of literature under the First and the Second Empire, this itinerary is rather an evocation of authors whose works were composed during these periods or inspired by them, it is an invitation to take a stroll through the houses which once belonged to them.

The itinerary is designed to take three days. The first of these days is dedicated to two writers linked to the First Empire: Chateaubriand, one of Napoleon’s most famous opponents, and Balzac, a genius who like Napoleon wished live out his own saga. The second day takes as its subject the Second Empire introducing the exceptional historical and literary figures Zola, Michelet and Flaubert. The last day concentrates on one author, Victor Hugo, a man whose life and work is inextricably linked to both the First and Second Empires.

Karine Huguenaud

(1996) -

Route : First day : Chateaubriand, Balzac

Our itinerary starts with an evocation of one of the greatest French writers of the early 19th Century: François-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848). The author of Génie du Christianisme (1802), Chateaubriand allied himself with the Consulat cause and was greatly impressed by what he perceived to be Napoleon’s abilities. For Bonaparte the feeling was mutual and in 1803 the First Consul appointed the writer to the post of secretary to the French Embassy in Rome under Cardinal Fesch; Chateaubriand was later promoted to the post of French minister to the Valais republic. But with the assassination of the Duke of Enghien in 1804 the writer distanced himself from Napoleon and directly criticized him in an article appearing in the Mercure in 1807: “When, in the silence of the abjection, the only sound that can be heard is the clink of the chains of a slave and the voice of the informer; when all tremble before the tyrant and it is as dangerous to incur his favor as to merit his disgrace, then the historian appears, bringing with him with the vengeance of the people.”

With the publication of this article, Chateaubriand was ordered by the imperial police to move away from Paris. Thus began his exile at the Vallée-aux-Loups estate in Châtenay-Malabry. And it was here that he wrote a large part of his account of his life, Mémoires d’Outre-tombe, a life which had been so closely linked to the history of the period. In 1814, he published a pamphlet entitled “De Buonaparte et des Bourbons” in which he denounced the Emperor as a usurper and even denied his military genius. But in the Mémoires – which only appeared after Chateaubriand’s death in 1848 – the writer in fact reveals himself as an admirer of Napoleon, consecrating gradually as the book progresses almost one third of this work to the great man. Although Chateaubriand recanted some of his former condemnations, he did not however become an unqualified supporter of the man and his actions: “Bonaparte was not great through his words, his speeches, his writings, or through love (which he never had) for liberties (which he never intended to establish); he is great for having created a regulated and strong government, a code of laws adopted in different countries, courts of justice, schools, a strong, active and intelligent administration which guides our lives still today; he is great for having revived, enlightened and established Italy better than anyone else could have done; he is great for having brought France out of chaos to renaissance […] he is great above all for, from illegitimate birth, having raised himself up by his own efforts to the height where thirty-six million subjects obeyed him, in an age when the crown had lost all credibility […] for having filled ten years with such wonders that it is hard today to comprehend them”.

During his lifetime Napoleon was for the most part celebrated by authors whose popularity was short-lived: “It is the mediocre writers who support me, not the great”, was the Emperor’s shrewd comment. In fact, Chateaubriand was not the only one to oppose Napoleon. Two other writers of note during the Empire period also expressed their disapproval, namely Germaine de Staël, exiled to Coppet in Switzerland in 1803 for her hard-line political, religious and social views, and Benjamin Constant (also exiled to Coppet), the author of a violent pamphlet entitled “De l’esprit de conquête et de l’usurpation” which appeared in 1814.

Our itinerary then brings you back towards Paris, to Passy, or more precisely to number 47 rue Raynouard, to Balzac’s house.

Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), a giant of French literature, drew his creative energy from the Napoleonic saga. Indeed, he even went so far as to have inscribed on the bust of Bonaparte which sat imposingly on the mantlepiece in his study in rue Cassini the words “All that he [Napoleon] did with the sword, I will accomplish with a pen”. In La Comédie humaine, (Balzac’s enormous literary canvass comprising series of novels grouped under the headings Scènes de la vie politique, Scènes de la vie privée, Scènes de la vie de Campagne and Scènes de la vie militaire), he observed and analyzed the French society which had emerged from the Revolution (a society which Napoleon had largely been responsible for forming) and cast everything in Napoleonic light.

For Balzac the act of writing was in itself a struggle of Napoleonic proportions: “When inspiration comes, all my intellectual forces shake in anticipation for the fight. My ideas move off like the battalions of the Grande Armée […] The infantry of memories charges in, banners streaming; the light cavalry of comparison spreads out in a magnificent gallop; the big guns of logic, with their wagons and shells, provide support; flights of genius come like sniper shots. The actors stand face-to-face. The paper gets covered in ink as battle commences. And as with battles and their black gunpowder, everything ends in a downpour of blackness. Each day is an Austerlitz of creation”.

Described by Paul Bourget as a “France’s own literary Napoleon”, Balzac represented the Emperor many times in his novels and short stories. He gave a direct version in the historical, detective novel Une Ténébreuse Affaire, from Scènes de la vie politique. He took a sideways glance at Napoleon both in the novel Une double Famille, from Scènes de la vie privée, and in his famous Colonel Chabert, the man whom all thought had died at the battle of Eylau. With Le Médecin de Campagne (from Scènes de la vie de Campagne) Balzac composed his most decidedly Napoleonic novel of the whole Comédie humaine, the narrator being an old soldier of the Empire named Goguelat. According to Balzac’s initial plan for the Comédie humaine, the series Scènes de la vie militaire was to recount the Napoleonic epic in its entirety. Of the twenty novels planned for this series only two were completed, namely Les Chouans and Une passion dans le désert, a curious story about a soldier in the Egyptian Army. Also of Napoleonic interest (and both published in the volume Etudes philosophiques) are the the piece entitled El Verdugo, set during the Spanish campaign, and the remarkable novella Adieu, where Balzac suddenly transports his reader to the icy plains of Russia with a poignant description of the crossing of the Berezina river.

-

Route : Second day : Second Empire

In the morning of the second day of this itinerary, we leave Balzac and his epic to go in search of the author who aimed to write a second Comédie humaine (this time based on France of the Second Empire), the man who wished to be considered as Balzac’s literary successor, Emile Zola (1840-1902).

Zola’s house is at Médan in the Yvelines, and on first entering you get the impression of stepping into one of the pages of his extraordinary saga novel, Les Rougon-Macquart. This saga was the double product of Zola’s respect for Balzac and his interest in physiology, and it is the study of a family with branches at all levels of society. Not simply a masterpiece of realistic observation, Les Rougon-Macquart, sub-titled Histoire naturelle et sociale d’une famille sous le Second Empire (Natural and social history of a family during the Second Empire), aimed at being an exhaustive depiction of imperial society.

Despite the overall plan for twenty novels being complete already by 1868, the first novel was not to appear until after the fall of the Empire in 1871. Zola did not however abandon the project but continued meticulously preparing for each book compiling huge dossiers of information on the social milieux about which he wished to write. When the saga was finished in 1893 he had created a vast canvass of more than 2000 characters.Les Rougon-Macquart remains the point of reference for the understanding of Second Empire society. Clearly Zola, a fervent republican, did not in the least share the government’s ideas. Indeed he even went so far as to become a confirmed opponent of the Empire, reiterating his attacks in his fairy tales (“Les Aventures du grand Sidoine et du petit Médéric”, Contes à Ninon, 1864) and in his articles for the opposition journals La Tribune, Le Rappel, and La Cloche.

Thus what we see of the Second Empire is therefore biased and incomplete: the political regime with its weaknesses and excesses is summarily condemmned, as is the immoral ammassing of riches and the proportional increase in poverty, and the dissolution of morals in a society under tension. That being said, his works give us a brilliant view of an entire epoch in flux, a fascinated vision of modernity on the move, notably: the great constructions and architecture of iron and glass, in La Curée and Le Ventre de Paris; the creation of department stores and of banks, in Au Bonheur des Dames and L’Argent; the railways, in La Bête humaine; conditions for the working classes and the beginnings of trade unions, in L’Assommoir and Germinal; the problems of the countryside and its peasants in La Terre; religion, in La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret; the triumphant middle classes, in Pot-Bouille; the education of girls, the role of women in society, particularly the party girls of the ‘Naughty Nineties’, in Une Page d’amour and Nana; art, in L’Oeuvre; etc.Fictional and historical characters rub shoulders as the plot weaves its way through the Second Empire period. La Fortune des Rougon, the first novel in the saga, recounts in parallel the origins of the family, and the origins of the Empire, namely the coup d’état which Zola considered as blood on the hands of the perpetrators. The government, the ministers, and the life at court (notably the receptions at the Tuileries and the famous Compiègne “series”) all figure in the different parts of the saga. Napoleon III (Genealogy) himself appears many times: notably in La Curée, Son Excellence Eugène Rougon and of course La Débâcle, the terrible story of the war of 1870 and the defeat at Sedan. The portrait that Zola presents of the Emperor is critical but not a caricature. Whilst Napoleon III appears a confused character, hesitant, hypocritical, poorly advised, a sentimental dreamer, a deluded waverer with humanist ideals, Zola also portrays him as a man of great courage when put to the test.

But the Les Rougon-Macquart saga is more than just a neurotic and pessimistic vision of the Second Empire, a mere collection of attacks launched against an authoritarian government and an inegalitarian society. It is also an immense historical document, a penetrating overview of industrialized civilisation in the second half of the 19th Century.

After this plunge into the realist universe of Zola, we continue our itinerary in the direction of Rouen and head for the house of one of the greatest historians of the 19th Century, Jules Michelet.

Although less well known to anglophone readers, Michelet (1798-1874) is not out of place in this walk dedicated to writers. Indeed, as aptly expressed in Taine’s epigram “Michelet writes like Delacroix paints”, Michelet’s writing style was of epic proportions. As the protégé of Guisot, he was elected to the College of France as professor in 1838. But because of his unabashed liberalism and anticlericalism, his courses on morality and history were suspended in 1851. As the famous memorialist of the Second Empire, the ruthless Viel-Castel, wrote on 12th March, 1851: “The government has finally closed the door on Michelet’s courses. During these courses, communism of the purest sort was openly taught; it was a real scandal.”

In 1853, for having refused to swear allegiance to the Emperor, Michelet was again dismissed, this time from the post of head of the historical section of the National Archives, a post which he had occupied since 1831. Refusing susequently to launch himself into politics, the historian left Paris to dedicate himself to his research. Here he completed his monumental Histoire des Temps Modernes publishing it over the period 1855 to 1867, finished La Bible humaine in 1864, and in 1869 wrote the general preface to the collection of volumes encompassing the complete Histoire de France.

As for his non-historical works, the most noteworthy are L’Amour (1858) and La Femme (1859) both of which had a profound influence on the young Zola as he discovered the importance of physiology. Withdrawing into very discreet opposition, Michelet foresaw with great perspicacity the fall of the Second Empire one year before it took place.Let us continue our stroll in the literary world of the Second Empire with an evocation of one of its most eminent figures, Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880). The Flaubert Pavilion at Croisset, a village very near to Rouen, is the only vestige left of the property where the writer wrote parts of his three masterpieces, Madame Bovary (1857), Salammbô (1862) and L’Education sentimentale (1869).

On the publication of Madame Bovary in 1857, Flaubert was taken to court in what was to become the first in a series of high profile literary court cases, and these trials give a very good idea of moral climate under the Second Empire. In fact in the same year, two other writers were to see their works attacked by the censor. The first, Eugène Sue, was prosecuted for the publication of his Mystères du Peuple, Histoire d’une famille de prolétaires à travers les âges. For what were considered “attacks against the authority” he received the exceedingly harsh sentence of one year in prison and a fine of 6000 francs. Sue died on August 3, 1857, and as a result of the trial which took place shortly after his death, the book was removed from the market and destroyed. The second author to come under fire was Charles Baudelaire, whose collection of poems Les Fleurs du mal was attacked by the newspapers almost as soon as it was published in June 1857. The poems were considered as being “in defiance of the laws protecting religion and morality”. Baudelaire’s sentence was a 300 franc fine and the removal of six poems from the edition. The poet appealed to the Empress Eugenie (Genealogy) herself for a reduction of the fine and this was eventually reduced to 50 francs on 20 January, 1858.

For all three trials Ernest Pinard, the Attorney General, was the prosecutor. Sue’s work was attacked for its political provocation, whilst Flaubert’s and Baudelaire’s books were criticised on esthetic grounds. The realistic intensity of Madame Bovary – serialised in la Revue de Paris October to December 1856 – caused a scandal despite its many cuts and the bowdlerisation of sensitive words like as “adultery” and insults such as “piece of beef”! The famous scene of the carriage in Rouen also fell victim to this censorship. Flaubert warned his readers that they were reading only fragments of his work.

When Madame Bovary was finally published in book form in April 1857 by Michel Levy, Flaubert was charged with insulting the public morality and offending decent manners. Whilst recognizing the stylistic unity of the novel, the attorney Pinard criticised its lewd character. The author and publishers were reprimanded but acquitted.From 1862 on – with his novel Salammbô a confirmed success – Flaubert began to limit his social life to strictly literary circles, first and foremost the “Magny dinners” where writers and artists such as Gavarni, the Goncourts, Sainte-Beuve, Baudelaire or Théophile Gautier gathered, and the salon of Princess Mathilde (Genealogy) in the rue de Courcelles. Despite the whiff of scandal, Flaubert finally received official recognition from the Second Empire when he was invited to Compiègne at the time of the famous “series”. There he received the Legion of honour on August 15, 1866, and in 1867 he was even invited to the Tuileries to a ball given in honour of the foreign sovereigns who came for the Exposition Universelle. It was in fact from Flaubert, with this first-hand experience of imperial circles, that Emile Zola in part took his descriptions in Les Rougon-Macquart.

-

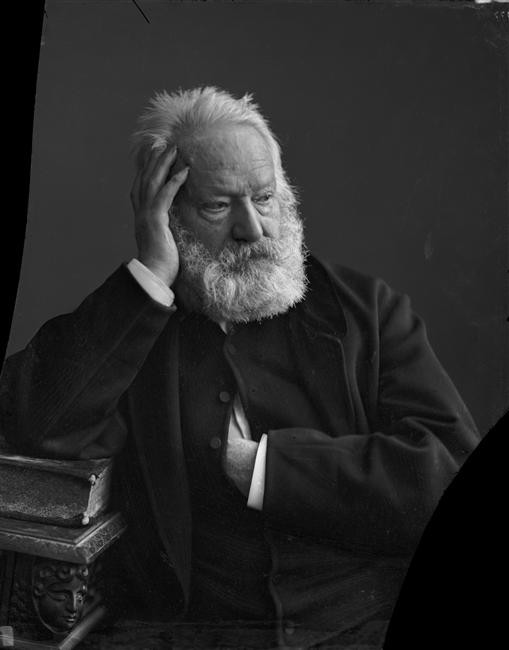

Route : Third day : Victor Hugo

This last day is entirely dedicated to Victor Hugo (1802- 1885) and two of his houses: Villequier (The Hugo Museum) with its memorabilia for the most part relating to his family and Victor Hugo’s House in the Place Vosges in Paris where the writer lived from 1833 to 1848.

Victor Hugo holds a special place in this itinerary, in that his personal history is closely linked to that of the First and Second Empires. Born in 1802, he very early on had first-hand experience of Napoleon through his father, General Léopold Hugo, a fervent supporter of the Emperor. However, the Hugo household was not unanimously pro-Napoleon. His mother, Sophie Trébuchet, was a Royalist, and it was this political opposition combined with personal disagreement which led to his parents’ separation. And so, even though the young Victor Hugo had experienced his father’s military life at close quarters, joining him in his different postings firstly in Naples in 1807 and secondly in Spain in 1809, nevertheless the future author – who proclaimed at 14 years, “I want to be Chateaubriand or nothing” – began his literary career under the double banner inherited from his mother, that of catholic and hard-line royalist. With his first collection of poems – published in 1822 – he mixed poetry with politics in order to sing the praises of the Bourbons and to curse the man whom, in one of his odes entitled, Buonaparte, he compared to a “living plague”.

But after the death of his mother, Victor Hugo became closer to his father – a man about whom he knew very little – and his influence proved a strong catalyst in leading the young Hugo to begin to see Napoleon in a positive light. The Nouvelles Odes of 1824 bear eloquent witness to this sea-change. In the poem A mon Père, written in 1823, Hugo expressed for the first time his admiration for the Napoleonic armies and his pride to be linked to the heros of the epic. His change of mind is further shown by the ode A l’Arc de Triomphe and subsequently by the poem Les Deux Iles published in Odes et Ballades in 1826. Structured on the antithesis “Praise” and “Blame”, Les Deux Iles is an attempt by Hugo to give an impartial judgement on the Emperor. But his admiration for Napoleon was not to be finally and unequivocally revealed until 1827 with his Ode à la Colonne de la place Vendôme, a poem intended as a reply to a calculated insult – where Napoleonic titles were deliberately omitted – inflicted upon four marshals of the Empire at a reception in the Austrian Embassy. In a spirit of national reconciliation (but also of reconciliation with his father), Hugo presented Napoleon as the equal of Charlemagne and of the kings who had made France great. From then on, he was happy to sing the praises of the Emperor and his epic history without reserve, notably in his poems: Souvenir d’enfance (in Les Feuilles d’Automne), A la Colonne, Napoléon II (in Les Chants du Crépuscule), and A l’Arc de Triomphe (in Les Voix intérieures), etc.

Victor Hugo gradually moved away from the legitimist party to join the camps of liberalism. Elected to the Chamber of peers in 1845, he called for the return from exile of the Bonaparte family before supporting in 1848 the electoral campaign of Louis-Napoleon (Genealogy). He even created with his sons a journal entitled L’Evénement, in which his last pre-election canvassing gesture was to publish a page with nothing on it except the name of the candidate repeated one hundred times. Nevertheless, after the election, he slowly distanced himself from the prince president, not so much because he did not receive the ministerial post promised to him (as some scholars would have it), but rather because the government did not fulfil his democratic expectations. During a debate in the Chamber on 17th July, 1851, he pointed out the dangers threatening France: “What! after Augustus are we to have Augustulus? Because we have had Napoleon the Great, must we have Napoleon the Small!” Thereafter, Victor Hugo became a committed leader of republican opposition and after the coup d’etat of 2nd December was forced to flee France.

Thoughout the Second Empire period, the writer lived in exile, first in Brussels, and later, on the Channel Islands Jersey and Guernsey. In 1859, the triumphant Empire granted amnesty to the exiles but Hugo refused it: “Faithful to the engagement that I have made with my conscience, I will live to the end the exile of liberty. When liberty returns, I will return”. Considering himself as a sort of guardian of France’s moral conscience, he published ferocious pamphlets against the imperial regime, both in prose (Napoléon le Petit (1852)) and in verse (Châtiments (1853)). He also expressed his antibonapartiste hate in texts which he kept in manuscript, only publishing them later in 1877-1878 under the title Histoire d’un Crime.

In exile, Victor Hugo published Les Contemplations (1856), La Légende des siècles (1859), Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866), and Homme qui rit (1869). He also completed Les Misérables, published in Brussels in 1862, a sweeping saga taking the reader through a part of the 19th Century, including an epic description of the Battle of Waterloo. By way of conclusion, here are a few famous verses from L’Expiation, one of Hugo’s masterpieces in the collection Châtiments:

«Waterloo! Waterloo! Waterloo! Dismal plain!

Pale death swirled together the sombre batallions

In your theatre of woods, hillocks and valleys,

Like a current bubbling up into an overfull urn.

Europe on one side, France on the other.

Carnage! from heros God took away all hope;

Victory, you were a deserter, and Fate was weary.

O Waterloo! I weep; and then I hold back my tears – alas! –

For these, the last soldiers of the final war

Were great; they had conquered the whole earth,

put twenty kings to flight, and had crossed the Alps and the Rhine,

And their soul sang in bugles of bronze!» -

Continuations

In Paris

The urban development in the capital undertaken first by Napoleon I and later by Napoleon III established the city as we know it today. The Louvre, the arc de Triomphe of the Carrousel, the Vendôme Column, the stock exchange, the Châtelet Fountain, the arc de Triomphe, the rue de Rivoli, the Madeleine church, etc. were all planned and built during First Empire, while the Opéra, the grand boulevards, the North Station, most of the Parisian gardens, again Louvre, etc. were the product of the Second Empire.

And if we add a few museums to this list (notably the Orsay Museum, the Invalides and Military Museum, the Museum of the Legion d’Honneur, the Marmottan Museum, and the Carnavalet Museum) then it can clearly be seen that Paris in its entirety as it stands today is a showcase for the two Empires.

Hauts-de-Seine

In terms of its wealth of Napoleonic memorabilia, one place, Rueil-Malmaison, beats all the others. To help you discover its sites and museums, we have made for you a special itinerary.

Yvelines

The national estate of the Château de Versailles is not to be missed.

Eure

The château de Bizy at Vernon, former property of Joseph Lesuire, general in in the Napoleonic campaigns from 1805 to 1811, is a beautiful site packed full First Empire memorabilia. Today, the château belongs to the descendants of Marshal Suchet, Duke d’Albufera.

Seine-Maritime

In place Charles de Gaulle in Rouen there is an equestrian statue of Napoleon. A work by Dubray begun in 1865, it was cast in bronze from Austrian cannons taken at Austerlitz. On the pedestal, a low-relief freize executed after a design by Isabey represents the Emperor’s visit to the factory of the Sévène brothers on 2nd November, 1806.

The model which Isabey made for this freize is held at the local Rouen Fine Arts Museum, as are other works relating to the First Empire. There are also notably paintings and sketches by Géricault of officers of the Grand Army. -

Curiosity corner

This Napoleonic itinerary was partly based on larger itinerary by the IledeFrance and HauteNormandie regions designed to take literature lovers on a tour of the houses of famous French authors. What follows completes the original itinerary.

The House of Mallarmé at VulainessurSeine, Seine et Marne

The House of Elsa Triolet and Louis Aragon at SaintArnoultenYvelines

The Datcha of Ivan Tourgeniev at Bougival, HautsdeSeine

The House of Alexandre Dumas Château Monte Cristo at PortMarly, Yvelines

The House of Maurice Maeterlinck Château Médan, Yvelines

The Pierre Corneille Museum at PetitCouronne, SeineMaritime

The House of Jean de la Varende Château Chamblac, Eure.For further information, contact the Route Historique des Maisons d’Ecrivains, 13, avenue d’Eylau 75116 Paris

Tel. : +33 (0)1.47.27.45.51

-

Bibliography

Further information and greater detail on the literary movements of the First and the Second Empires:

Précis de littérature française du XIXe siècle, edited by Madeleine Ambrière, PUF, 1990.

Descotes Maurice, La Légende de Napoléon et les écrivains du XIXe siècle, Minard, 1967.

L.H. Lecomte, Napoléon et le monde dramatique, Daragon, 1912.

P. Martino, Le Roman réaliste sous le Second Empire, Slatkine, 1973, (re-edition.).

The texts mentioned in the course of this itinerary:

Today, many publishers produce these texts in paperback with prefaces, commentaries, and sometimes even critical essays. Hence, we only indicate here reference works, recent publications or specific studies.

BALZAC / La Comédie humaine, edited by P.G. Castex, Gallimard, «Pléiade» collection, 1976-1961, 12 vols.

Adieu, Le Livre de Poche, Les Classiques d’Aujourd’hui, 1995.

Gérard Gengembre, Balzac le Napoléon des Lettres, Découverte Gallimard, n°150, 1992.CHATEAUBRIAND / Mémoires d’outre-tombe, critical edition by J.C. Berchet, Classiques Garnier, Bordas, 1989.

Mémoires d’outre-tombe, text of the original edition (1849), preface, notes and commentary by Pierre Clarac, Le Livre de Poche, 1995.

Sainte-Beuve, Chateaubriand et son groupe littéraire sous l’Empire, Garnier, 1948, (réed.).FLAUBERT / Oeuvres complètes, Editions Rencontre, critical edition by M. Nadeau, 1964-1965, 16 vols.

Oeuvres complètes, Club de l’Honnête Homme, critical edition by M. Bardèche, 1971-1976, 18 vols.HUGO / Oeuvres poétiques, critical edition by P. Albouy, Gallimard, «Pléiade» collection, 1964-1974, 3 vols.

The only edition of complete works presently available is:

Oeuvres complètes, edited by J. Seebacher, with Guy Rosa, Laffont, Bouquins collection, 1985.MICHELET / Oeuvres complètes, critical edition by P. Viallaneix, Flammarion, 1971, 14 vols.

ZOLA / Les Rougon-Macquart, critical edition by H. Mitterand, Gallimard, «Pléiade» collection, 1960-1967, 5 vols.

Les Rougon-Macquart, Laffont, Bouquins collection, 1991-1993, 5 vols. Critical edition presented and annotated by C.Becker, with G.Gourdin-Servenière and V. Lavielle.

Descotes Maurice, «Le personnage de Napoléon III dans les Rougon-Maquart», Archives des Lettres modernes, n°114, 1970.

«Le Second Empire vu et jugé par Zola», L’Information historique, XV, n°2, March-April 1953, p.50-57.

-

Practical information

Access

HOUSE OF BALZAC

47, rue Raynouard 75016 PARIS

Tel.: +33 (0)1.42.24.56.38

Open everyday from 10 a.m. to 5:40 p.m. except Monday .

Metro: La Muette, Passy

Bus n° 32, 52, 72HOUSE OF CHATEAUBRIAND – LA VALLEE AUX LOUPS

87, rue Chateaubriand 92290 CHATENAY-MALABRY (Hauts-de-Seine)

Tel.: +33 (0)1.47.02.58.61

Fax: +33 (0)1.47.02.05.57

Open everyday from 10 a.m. to noon and from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. from April 1 to September 30 and from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. from October 1 to March 31. Closed Monday. Tuesday and Thursday reserved for groups by appointment.

By car: from Paris pont de Sèvres, take the A86; come off at the Créteil exit; follow Avenue de la Division Leclerc, avenue Roger Salengro, then rue Eugène Sinet and rue Chateaubriand. Parking rue d’Aulnay 200 yards away (120 places). From Versailles take the RD 986.

RER: line B Robinson station, then follow the signposted pedestrian path about 20 minutes.HOUSE OF ZOLA

26, rue Pasteur 78670 MEDAN (Yvelines)

Tel.: +33 (0)1.39.75.35.65

Fax: +33 (0)1.39.75.59.73

Open Saturdays and Sundays from 2p.m. to 6 p.m. and by appointment during the week for groups.

By car: take the A13 or A14 and come off at the Poissy-Villennes-sur- Seine-Médan exit

SNCF: Villennes StationMICHELET MUSEUM – VASCOEUIL CASTLE

rue Michelet 27910 VASCOEUIL (Eure)

Tel.: +33 (0)2.35.23.62.35

Open everyday from Easter to 1st November from 2:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. and mornings by appointment for groups.

By car: 120 km from Paris. Take the A15 (Défense-Pontoise), then the RN14 and then D1 to Fleury-sur Andelle or take the A13, come off at the Pont-de-l’Arche exit and then take the N321 (signposted).

20 km from Rouen take the RN 31 after Martainville.

SNCF: Rouen or Le Vaudreuil StationsFLAUBERT PAVILION

18, quai Gustave Flaubert DIEPPEDALLE-CROISSET, 76380 CANTELEU (Seine-Maritime)

Tel.: +33 (0)2.35.36.43.91

Open everyday from 10 a.m. to noon and from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. Closed Tuesdays and Wednesday mornings.

By car: from Rouen follow the D982 for 9 kilometres direction Duclair then take the D51 towards CroissetVICTOR HUGO MUSEUM

rue Ernest Binet 76490 VILLEQUIER / CAUDEBEC-EN-CAUX (Seine-Maritime)

Tel.: +33 (0)2.35.56.78.31

Fax: +33 (0)2.35.56.04.89

Open everyday fom November 1 to February 28 from 10 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. ; from March 1 to October 31 from 10 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and from 2 p.m. to 6:30p.m. Closed Tuesdays and national holidays.

By car: from Rouen take the right bank toward Canteleu and then Caudebec; take the D81 following the course of the Seine to Villequier. To return to Paris, follow signs to Pont de Brotonne and then take the A13 (Bourg-Achard junction).

SNCF: Yvetot Station then a 14 km drive.HOUSE OF VICTOR HUGO

6, place des Vosges 75004 PARIS

Tel.: +33 (0)1.42.72.10.16

Fax: +33 (0)1.42.72.06.54

Open everyday from 10 a.m. to 5:40 p.m. Closed Mondays and national holidays.

Metro: Saint-Paul, Bastille, Chemin-Vert

Bus n°20, 29, 65, 69, 76, 96

The Authors of Napoleon

Chateaubriand, Balzac, Zola, Michelet, Hugo, and many others, all contributed to the Napoleonic legend.

Discover their homes!

1878 Photo (C) Ministère de la Culture - Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Atelier de Nadar