It was on the immense 62.5-acre (25-hectare) stretch of wasteland between Belleville and La Villette that Haussmann and Alphand chose to construct one of the most extraordinary Parisian parks of the Second Empire, the “Parc de Buttes-Chaumont”. The name, derived from a contraction of the French words Monts chauves (bald hills), aptly describes the bare mounds which formed the westernmost promontory of the Belleville hills. A public dump and site of Montfaucon gibbet, immortalised by François Villon in his Ballade des pendus, the Buttes-Chaumont area was used as a gypsum quarry and a knackers yard. In 1851, with the opening of the rue Crimée and the digging of cuttings for the railway, the quarries were effectively hemmed in. Even so, in 1863 there were still eight hundred men employed there producing plaster. Centuries of mining had made an already tortured site into an almost lunar landscape – no soil, only slag – and the enormous hollows in the rock served as shelter for the very destitute of a local population already very poor.

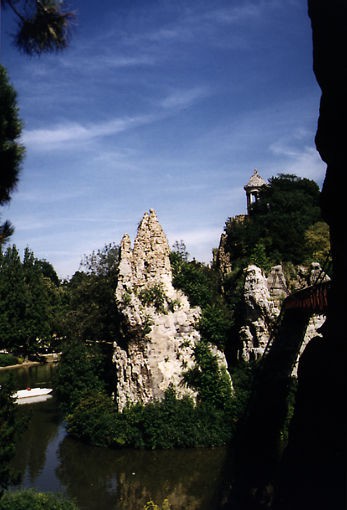

When Haussmann and Alphand chose this site as an response to Napoleon III's desire to offer to the working classes green spaces, 'lungs' to enable the city to breathe, they took on a project which was to last three years from 1864 to 1867. The construction work was on such a scale that a light railway had to be built to ferry excavations out and to bring in-fill in – all this simply to clean up the area so as to create a pleasant public park. In the centre of the park they dug a five acre (two hectare) lake. On an island in the centre of the lake there towered a 90-foot rocky peak crowned with a classical temple, the route to which was via two bridges – one a suspension bridge, the other a high arch – or by boats. From there, there were the 200 steps of the Aiguilles path to climb before reaching the top. One of the two man-made streams feeding the lake cascaded in a 90-foot waterfall, falling into a cave whose ceiling was decorated with artificial stalactites.

When the park was opened during the Universal Exhibition of 1867 it was an unqualified success and Alphand was given the sobriquet the “Artist Engineer”. But once the novelty had passed, the middle classes abandoned the Buttes-Chaumont park because they felt the factories of La Villette were too close. On the other hand, the working classes soon adopted the park which had been built for them, although they did not quite show as much respect to park regulations as they should have done – they picked the flowers, tore up the bushes, trampled the lawns, and even stripped the pine trees of their needles to make herbal infusions! These days, the public fortunately shows more respect to the magnificent sweeping lawns and the herbaceous borders and flower beds of this park which is still today one the finest in the capital.

Discover more about the Buttes-Chaumont Park and the other green spaces provided for Paris by the Second Empire. Take a wander around our itinerary “Parks and Gardens: Parisian strolls of the Second Empire”.

Buttes-Chaumont Park