Analysis of what is known concerning this manuscript

There are evocative names that have passed into a sort of collective unconscious. “Austerlitz” is one of them. Some will only see it as a Parisian railway station, perhaps unaware that it’s named after the bridge built during the First Empire. However, beyond the railway station, there are still many people who know of the world-famous battle of 2 December, the celebrated “sunshine”, and the military glory that Napoleon gained from this name with its Germanic overtones. As a result, when a Parisian bookseller puts on sale an account of the battle dictated and corrected by Napoleon on St Helena, the whole world sits up and pays attention!

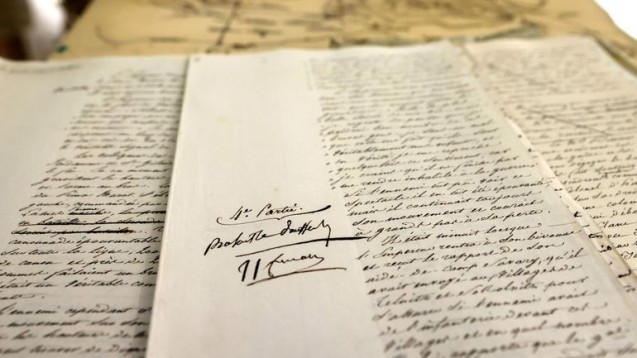

Throughout his reign, Napoleon painstakingly constructed his own “legend”, and St Helena was to become the keystone. During the six years of exile, via his companions Las Cases, Bertrand, Gourgaud and Montholon, Napoleon lived in the past, endlessly going over the glorious episodes of his reign. As part of what Thierry Lentz has baptised the “History factory”, Napoleon laid down what he wanted to be remembered about him. Right up until the year 1820, he kept on reworking the texts of his Memoirs, adding comments and corrections that came not just from his own memory and but that had also been stimulated by the books sent up to Longwood House. The texts taken down from dictation by his companions in exile (here demoted to mere secretaries) were then re-copied by Saint-Denis before being re-read and then re-adjusted. For the Egyptian campaign alone (dictated to Bertrand), multiple versions and drafts have survived and are held at the French National Archives, the French Bibliothèque Nationale, and the Médiathèque in Châteauroux. On 25 April 1821, ten days before his death, Napoleon ordered his Grand Marshal to publish and “dedicate his campaigns in Italy and Egypt to his son; [saying] that Caesar, Turenne and Frederic were of little worth.” These texts were the only ones he himself considered finished; indeed he even momentarily considered destroying those he had not had the will or the strength to finish. A few days later, however, Bertrand received from Montholon almost all the work the latter had participated in.

From 1821 and until 1830, following the Emperor’s wishes, these texts would be published in two multi-volume publications, namely the Recueil des pièces authentiques sur le captif de Sainte-Hélène and the Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de France sous le règne de Napoléon (the latter translated into English at the time). However, Bertrand still possessed many other works dictated on the political and military events of the reign, works on artillery and engineering and book commentaries. A huge amount of material that the excessively conscientious Bertrand had neither the time nor the desire to publish. His descendants handed over some of the unpublished works to the commission for the publication of the Correspondance de Napoléon under Napoleon III, and they published them in volumes 30 to 32 of that collection. The descendants also gave a few bundles to Prince Victor Napoleon (these are now held at the French National Archives).

However, the majority of them remained shut up in the Grand Marshal’s heirs’ cupboards.

The Austerlitz manuscript currently on sale at a pretty steep price was among these latter precious archives. The first sales of the Bertrand papers took place in the 1970s, and this enabled the French National Archives to complete what they already had in the Bertrand private archive (390 AP). It was during these very first sales that the bookseller acquired this manuscript. The rest of the papers were dispersed during sales that took place in the 1980s. The world was then witness to immense wealth of archival material kept by Bertrand and then his family. Of these precious documents, which covered the entire history of the Empire, the major French institutions captured only a tiny part. Napoleon was not “fashionable” in the world of culture at that time, and a large part of the documents and letters were bought by private collectors. These archives periodically come back on sale, hence this manuscript.

Everyone knows the story of the battle of 2 December 1805. The smoke from the battlefield had barely cleared and the last wounded men were still on the battlefield when Napoleon was already writing the outlines of his account. He wrote his proclamations so that they would make him appear a brilliant strategist who had second-guessed his enemies’ plans. In the Bulletins de la Grande Armée that were published in the days following the battle, he presented the victory as inevitable, and painted the Austro-Prussian retreat much more catastrophic than it actually was. Keen as he was to leave a lasting memory of this dazzling victory, he asked Berthier in 1806 to write an official report on it like the one his chief of staff had done for Egypt and Marengo. The final text did not meet with the Emperor’s satisfaction, and the Prince de Neufchâtel’s effort was to end up in the War Archives (today the French Service Historique de la Défense). Without in any way wishing to undercut the heritage value and interest of this text, this dictation on Austerlitz taken down by Bertrand was inspired by these texts and goes over the major phases of the battle. As can be seen from the excerpts to which we have had access, the text is written, like the Memoirs, in the third person singular, and it shows Napoleon staging himself, making no revelations whatsoever, and turning the events to his advantage. The distance that Napoleon takes with his stories is quite frustrating. We would much rather that he gave his honest impressions of the events of which he was the architect. Las Cases’s Mémorial, le manuscrit retrouvé, Gourgaud’s Journal integral, and Bertrand’s Cahiers (soon to be published by Perrin) are probably more instructive.

Regardless, the fact remains that this manuscript relating one of the most famous battles of the Empire bears the autographs of two of its actors: Bertrand who took part in it as the Emperor’s aide-de-camp and Napoleon who was the brilliant strategist.

François Houdecek

January 2021

François Houdecek is special projects manager at the Fondation Napoléon.

Press review

French

• Un manuscrit unique racontant la bataille d’Austerlitz mis en vente à 1 million d’euros, GÉO, 20/1/2021

• Quand exilé à Sainte-Hélène, napoléon se remémorait la bataille d’Austerlitz, Le Point, 23/1/2021, and 27/1/2021

• Un manuscrit de Napoléon bientôt mis en vente, Le Bien public, 25/1/2021

• Un manuscrit de Napoléon bientôt aux enchères, Le Progrès, 25/1/2021

• Video: Un manuscrit unique au monde dicté et annoté par Napoléon mis aux enchères à Paris, Le Figaro, 26/1/2021

• Video: Découverte – les dessous de la bataille d’Austerlitz à travers un manuscrit de Napoléon Bonaparte, France TV Info, 27/1/2021

International

• Un manuscrit de Napoléon sur la bataille d’Austerlitz en vente pour 1 million d’euros, RTBF, 27/1/2021

• Napoleon’s manuscript on victory at Battle of Austerlitz goes on sale, The Guardian, 27/1/2021

• Napoleons manuscript van slag bij Austerlitz te koop voor 1 miljoen, Business AM, 27/1/2021

• Venden en Francia manuscrito de Napoleón sobre batalla de Austerlitz, Prensa Latina, 27/1/2021

• Napoleon’s account of legendary Battle of Austerlitz goes on sale, New Indian Express, 27/1/2021

• Francia:in vendita manoscritto di Napoleone su Austerlitz, Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata, 27/1/2021