This is one of the best-known stories about Napoleon Bonaparte. It is a moment of glory which highlights one man’s successful rise, from Corsican general to Emperor of the French. But what is it really all about?

What is a sacre?

Well, a coronation is an event where a monarch is crowned and power is transferred to the ruler. A sacre, on the other hand, is a religious ceremony of consecration which makes temporal (non-religious) power holy.

Napoleon found inspiration for his sacre from that of Emperor Charlemagne, who he admired greatly.

Why did Napoleon want to be consecrated?

On 2 December 1804, Napoleon had already been Emperor of the French for seven months! The official document, or Sénatus-consulte, confirming his imperial rank had been published on 18 May 1804. His consecration had a political purpose.

- He wanted to follow on from the long line of emperors and kings in Europe and in France, notably Charlemagne who had been consecrated by the Pope on 25 December 800. Napoleon also wanted to prove his prestige alongside kings from neighbouring countries.

- After Catholicism had been banned by the French revolution, Napoleon’s invitation of Pope Pius VII to come and consecrate him in Notre Dame was part of the Emperor’s policy to reconcile Catholics to the regime, but also to mark his power over Catholicism.

This portrait of Pope Pius VII by the painter David is well known for its precise reflection of the Pope’s character, showing a look of candid determination. However, the subtle smile softens the sharpness of that look and highlights one of the values attributed to the Pope, his goodwill. Pius VII was acclaimed by the French population both during his journey from Rome and also when he arrived in the French capital four days before the ceremony.

Pope Pius VII comes to Paris

It was very important for Napoleon to be seen as distinct from the tradition of the kings who had preceded him and so he made sure he was consecrated by the Pope himself and not by a bishop. It was also important for him that Pope Pius VII should bless him, as relations between France and the Vatican (the state run by the Pope from the Vatican Hill in Rome, otherwise known as the Holy See) had been tense between 1796 and 1800. This was not surprising, given the French Republic’s invasion of the Papal States and taking of Pius VII’s predecessor, Pius VI, prisoner. That pope had even died in captivity in France.

In 1800, Bonaparte restored the Papal States under the new Pope, Pius VII, but kept part of them for himself. He signed an agreement with Pius called the Concordat in 1801, which reinstated papal authority over French churches. Catholicism re-affirmed its place as the primary religion of France, but was not made a state religion as it had been under the monarchy of the Ancien Régime.

This new situation should have appeased the relations between France and the Vatican, but less than a year after the Concordat was signed Bonaparte appended to the document with articles drawn up unilaterally which asserted the precedence of the French republic over the authority of the Pope.

Napoleon therefore wanted to be consecrated by Pius VII so that he could put an end to the debate over papal authority in France. Although Pius was invited to come to France, he was invited with the expectation that he would accept the terms of this new ‘contract’. Pius VII agreed to come and consecrate Napoleon, but hoped to renegotiate these articles.

Preparing the sacre

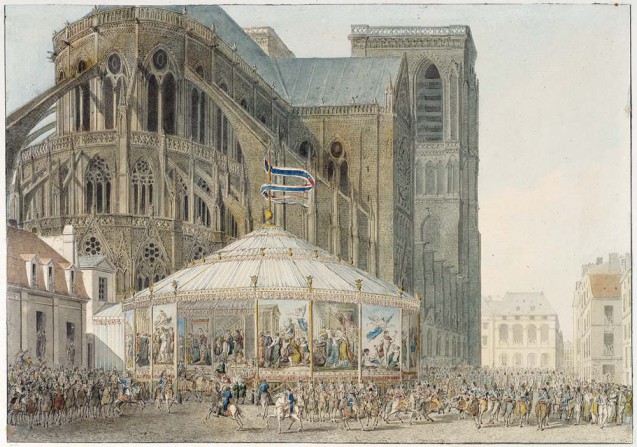

Although French kings were usually consecrated in Reims, Napoleon decided that Paris and the cathedral of Notre Dame would be better suited as centre stage for the action in addition to setting himself apart from Louis XVI and his antecedents (the rulers that came before him). That religious building could contain 20,000 people and could also provide shelter from the bad weather (it was after all to be held on 2 December). Outdoors, nearby buildings were demolished in order to make a bigger space for Parisians to gather, in order to witness the event.

These preparations only took three months – a record time – to complete. All the craftspeople, dressmakers, embroiderers and jewellers of the city worked in preparation for the sacre. As well as working on the costumes for Napoleon, Josephine, and the imperial family, they also made costumes for the great dignitaries. Among those invited were: the Marshalls Moncey, Sérurier and Murat; Chamberlain Talleyrand; and ministers, processing in lines of four. Parisian embroiderers were hugely overworked and soon had to appeal to Lyon, a town reputed for its textile trade, for supplementary workers.

As for transport, a carriage was designed especially for the ceremony. It was covered in gold and coated with velvet upholstery, white inside, and green embroidered with the initial N for Napoleon on the outside. Three gilt eagles held aloft a golden crown. The occasion certainly did not lack in splendour, and spectators even hired bedrooms and balconies close to Notre Dame not to miss out on the forty-carriage procession.

A long, long ceremony

At midnight, canon salvoes (several canons firing simultaneously) announced the sacre, and at 6 o’clock in the morning bells were rung. On the day itself, the 12,000 invitees hurried into the cathedral square. The second of December 1804 was a cold and overcast day, and it had even snowed during the whole of the previous night.

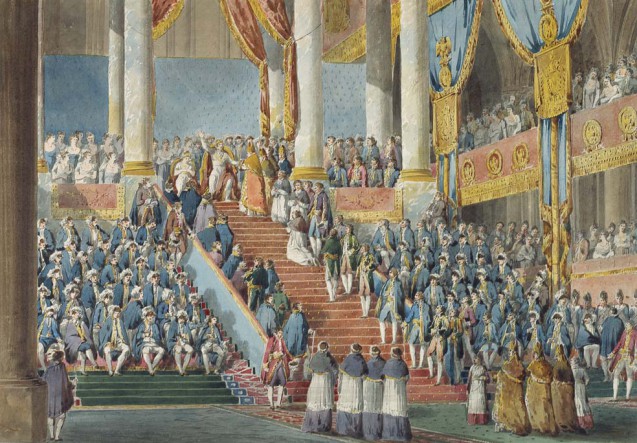

Between 10 and 11 o’clock on 2 December not many people were gathered outside to see the procession take off from the Tuileries palace and make its way towards Notre Dame. Things were running late for the new Emperor. And yet Napoleon carefully adjusted the ceremony by means of a model, the same that allowed invitees to get to their allotted places in the cathedral. The Imperial couple entered the part of the cathedral near the high altar, called the Choir, slightly before midday. At this point the ceremony started and Pope Pius VII performed the consecration. Since the ceremony went on for a punishing three hours, guests had to put up with it as best as they could. Some had brought food and others had drinks – the building was freezing, it was December after all, and the doors had stood wide open all morning.

This is one of the moments in the sacre where Napoleon lifted his right hand to take an oath obliging him to respect the constitution.

The self-crowning Emperor: an unforgettable move

Quite unlike anything that had been done before, Napoleon picked up the crown resting on the altar and put it on his head, following the agreed order of service. He then proceeded to crown Josephine, a moment that the painter David chose to depict in his impressive representation of the scene, Le Sacre (The Consecration). This symbolic gesture emphasized the political but also spiritual power that Napoleon aimed to wield over Pope Pius VII.

After putting the crown of golden laurels on his head, Napoleon crowned Josephine Empress of the French in the presence of Pius VII, shown here sitting behind them during the whole process.

The month of celebrations after the sacre

The procession back to the Tuileries crossed districts of Paris where the streets had been strewn with flowers and paper lanterns and the Imperial couple was cheered by an enthusiastic crowd. That December in Paris saw a whole host of celebratory events, such as receptions and official ceremonies. On 5 December, on the Champ-de-Mars, Napoleon handed out standard eagles to representatives of the army as symbols of military power. Public entertainments were organised in Paris and throughout the whole empire, varying from floats bearing musicians to dances, and street entertainments. There were also firework displays and balloon releases, and medals were distributed, stamped with the face of the Emperor of the French.

Have a look at this digital model of Napoleon’s Coronation and Consacration.

Marie de Bruchard, March 2017 (translation: Elizabeth Gornall and Peter Hicks)