Transcription

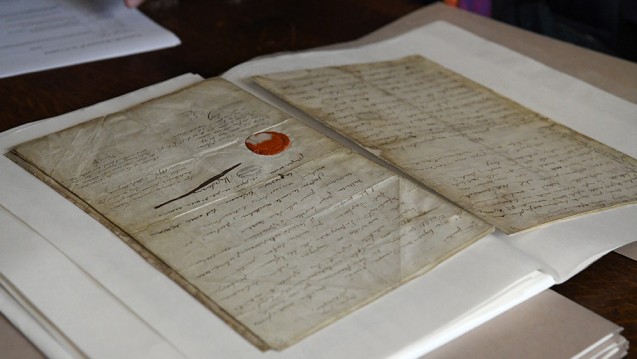

This 15th April, 1821, at Longwood, Island of St Helena.

This is my Testament, or act of my last will.

I

1. I die in the Apostolical Roman religion, in the bosom of which I was born more than fifty years since.

2. It is my wish that my ashes may repose on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people, whom I have loved so well.

3. I have always had reason to be pleased with my dearest wife, Maria Louisa. I retain for her, to my last moment, the most tender sentiments—I beseech her to watch, in order to preserve, my son from the snares which yet environ his infancy.

4. I recommend to my son never to forget that he was born a French prince, and never to allow himself to become an instrument in the hands of the triumvirs who oppress the nations of Europe: he ought never to fight against France, or to injure her in any manner; he ought to adopt my motto: “Everything for the French people.”

5. I die prematurely, assassinated by the English oligarchy and its assassin. The English nation will not be slow in avenging me.

6. The two unfortunate results of the invasions of France, when she had still so many resources, are to be attributed to the treason of Marmont, Augereau, Talleyrand, and La Fayette. I forgive them–May the posterity of France forgive them as I do.

7. I thank my good and most excellent mother, the Cardinal, my brothers, Joseph, Lucien, Jerome, Pauline, Caroline, Julie, Hortense, Catarine, Eugene, for the interest they have continued to feel for me. I pardon Louis for the libel he published in 1820: it is replete with false assertions and falsified documents.

8. I disavow the “Manuscript of St. Helena,” and other works, under the title of Maxims, Sayings, &c., which persons have been pleased to publish for the last six years. Such are not the rules which have guided my life. I caused the Duc d’Enghien to be arrested and tried, because that step was essential to the safety, interest, and honour of the French people, when the Count d’Artois was maintaining, by his own confession, sixty assassins at Paris. Under similar circumstances, I would act in the same way.

II.

1. I bequeath to my son the boxes, orders, and other articles; such as my plate, field-beds, arms, saddles, spurs, chapel-plate, books, linen which I have been accustomed to wear and use, according to the list annexed (A). It is my wish that this slight bequest may be dear to him, as coming from a father of whom the whole world will remind him.

2. I bequeath to Lady Holland the antique Cameo which Pope Pius VI. gave me at Tolentino.

3. I bequeath to Count Montholon, two millions of francs, as a proof of my satisfaction for the filial attentions be has paid me during six years, and as an indemnity for the loses his residence at St. Helena has occasioned him.

4. I bequeath to Count Bertrand, five hundred thousand francs.

5. I bequeath to Marchand, my first valet-de-chambre; four hundred thousand francs. The services he has rendered me are those of a friend; it is my wish that he should marry the widow, sister, or daughter, of an officer of my old Guard.

6. Idem, to St. Denis, one hundred thousand francs.

7. Idem, to Novarre (Noverraz,) one hundred thousand francs.

8. Idem, to Pierron, one hundred thousand francs.

9. Idem, to Archambault, fifty thousand francs.

10. Idem, to Coursot, twenty-five thousand francs.

11. Idem, to Chandelier, twenty-five thousand francs.

12. To the Abbé Vignali, one hundred thousand francs. It is my wish that he should build his house near the Ponte Nuovo di Rostino.

13. Idem, to Count Las Cases, one hundred thousand francs.

14. Idem, to Count Lavalette, one hundred thousand francs.

15. Idem, to Larrey, surgeon-in-chief, one hundred thousand francs.–He is the most virtuous man I have known.

16. Idem, to General Brayer, one hundred thousand francs.

17. Idem, to General Lefebvre-Desnouettes, one hundred thousand francs.

18. Idem, to General Drouot, one hundred thousand francs.

19. Idem, to General Cambronne, one hundred thousand francs.

20. Idem, to the children of General Mouton-Duvernet, one hundred thousand francs.

21. Idem, to the children of the brave Labédoyère, one hundred thousand francs.

22. Idem, to the children of General Girard, killed at Ligny, one hundred thousand francs.

23. Idem, to the children of General Chartrand one hundred thousand francs.

24. Idem, to the children of the virtuous General Travot, one hundred thousand francs.

25. Idem, to General Lallemand the elder, one hundred thousand francs.

26. Idem, to Count Réal, one hundred thousand francs.

27. Idem, to Costa de Bastelica, in Corsica, one hundred thousand francs.

28. Idem, to General Clauzel, one hundred thousand francs.

29. Idem, to Baron de Méneval, one hundred thousand francs.

30. Idem, to Arnault, the author of Marius, one hundred thousand francs.

31. Idem, to Colonel Marbot, one hundred thousand francs.–I recommend him to continue to write in defence of the glory of the French armies, and to confound their calumniators and apostates.

32. Idem, to Baron Bignon, one hundred thousand francs.–I recommend him to write the history of French diplomacy from 1792 to 1815.

33. Idem, to Poggi di Talavo, one hundred thousand francs.

34. Idem, to surgeon Emmery, one hundred thousand francs.

35. These sums will be raised from the six millions which I deposited on leaving Paris in 1815; and from the interest at the rate of 5 per cent. since July 1815. The account thereof will be settled with the banker by Counts Montholon and Bertrand, and Marchand.

36. Whatever that deposit may produce beyond the sum of five million six hundred thousand francs, which have been above disposed of, shall be distributed as a gratuity amongst the wounded at the battle of Waterloo, and amongst the officers and soldiers of the battalion of the Isle of Elba, according to a scale to be determined upon by Montholon, Bertrand, Drouot, Cambronne, and the surgeon Larrey.

37. These legacies, in case of death, shall be paid to the widows and children, and in default of such, shall revert to the bulk of my property.

III.

1. My private domain being my property, of which I am not aware that any French law has deprived me, an account of it will be required from the Baron de la Bouillerie, the treasurer thereof: it ought to amount to more than two hundred millions of francs; namely, 1. The portfolio containing the savings which I made during fourteen years out of my civil list, which savings amounted to more than twelve millions per annum, if my memory be good. 2. The produce of this portfolio. 3. The furniture of my palaces, such as it was in 1814, including the palaces of Rome, Florence, and Turin. All this furniture was purchased with moneys accruing from the civil list. 4. The proceeds of my houses in the kingdom of Italy, such as money, plate, jewels, furniture, equipages; the accounts of which will be rendered by Prince Eugene and the steward of the Crown, Campagnoni.

2. I bequeath my private domain, one half to the surviving officers and soldiers of the French army who have fought since 1792 to 1815, for the glory and the independence of the nation, the distribution to be made in proportion to their appointments upon active service; and one half to the towns and districts of Alsace, Lorraine, Franche-Comté, Burgundy, the Isle of France, Champagne, Forez, Dauphiné, which may have suffered by either of the invasions. There shall be previously set apart from this sum, one million for the town of Brienne, and one million for that of Méry. I appoint Counts Montholon and Bertrand, and Marchand, the executors of my will.

This present will, wholly written with my own hand, is signed and sealed with my own arms.

NAPOLEON

List (A).

1. None of the articles which have been used by me shall be sold; the residue shall be divided amongst the executors of my will and my brothers.

2. Marchand shall preserve my hair, and cause a bracelet to be made of it, with a little gold clasp, to be sent to the Empress Maria Louisa, to my mother, and to each of my brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, the Cardinal; and one of larger size for my son.

3. Marchand will send one pair of my gold shoe-buckles to Prince Joseph.

4. A small pair of gold knee-buckles to Prince Lucien.

5. A gold collar-clasp to Prince Jerome.

Inventory of my effects, which Marchand will take care of, convey to my son.

My silver dressing-case, that which is on my table, furnished with all its utensils, razors, &c. My alarum-clock: it is the alarum-clock of Frederic II. which I took at Potsdam (in box No. III.). My two watches, with the chain of the Empress’s hair and a chain of my own hair for the other watch: Marchand will get it made at Paris. My two seals (one the seal of France, contained in box No. III.). The small gold clock which is now in my bed-chamber. My wash-hand-stand and its water-jug. My night-tables, those used in France, and my silver-gilt bidet. My two iron bedsteads, my mattresses, and my coverlets, if they can be preserved. My three silver decanters, which held my eau-de-vie., and which my chasseurs carried in the field. My French telescope. My spurs, two pairs. Three mahogany boxes, Nos. I. II. III., containing my snuff-boxes and other articles. A silver-gilt perfuming pan.

Linen: 6 shirts, six handkerchiefs, 6 cravates, six towels, six pairs of silk stockings, four black collars, six pairs of socks, 2 pairs of batiste sheets, 2 pillow cases, 2 dressing gowns, 2 pairs of night trousers, 1 pair of braces, 4 all-in-one vests in white casimir, 6 madras kerchiefs, 6 flannel waistcoats, 4 pairs of underpants, 6 pairs of gaiters, 1 small box for my tobacco, 1 gold collar-clasp (in small box number III), 1 pair of gold knee-buckles (idem), 1 pair of gold shoe-buckles (idem)

Dress: 1 chasseurs uniform, 1 ditto grenadiers, 1 ditto Garde nationale, 2 hats, 1 grey and green cape.

1 blue coat (that which I wore at Marengo), 1 green, sable-trimmed greatcoat, 2 pairs of shoes, 1 pair of slippers, 6 belts/

NAPOLEON

List (A). Annexed to my Will. / Longwood, Island of St. Helena, this, 15th April, 1821.

List (A). Annexed to my Will

Longwood, Island of St. Helena, this, 15th April, 1821.

I

The consecrated vessels which have been in use at my Chapel at Longwood. I direct Abbé Vignali to preserve them, and to deliver them to my son when he shall reach the age of sixteen years.

II.

My arms; that is to say, my sword, that which I wore at Austerlitz, the sabre of Sobiesky, my dagger, my broad sword, my hanger, my two pair of Versailles pistols.

My gold dressing-case, that which I made use of on the morning of Ulm and of Austerlitz, of Jena, of Eylau, of Friedland, of the Island of Lobau, of the Moskova, of Montmirail. From this point of view it is my wish that it may be precious in the eyes of my son. (It has been deposited with Count Bertrand since 1814.): I charge Count Bertrand with the care of preserving these objects, and of conveying them to my son when he shall attain the age of sixteen years.

III

Three small mahogany boxes, containing, the first, thirty-three sluff-boxes or comfit-boxes; the second, twelve boxes with the Imperial arms, two small eye-glasses, and four boxes found on the table of Louis XVIII in the Tuileries, on the 20th of March, 1815; the third, three snuff-boxes ornamented with silver medals habitually used by the Emperor, and sundry articles for the use of the toilet, according to the lists numbered I. II. III. My field-beds, which I used in all my campaigns. My field-telescope. My dressing-case, one of each of my uniforms, a dozen shirts, and a complete set of each of my costume suits, and generally of every thing used in my dressing. My wash-hand stand. A small clock which is in my bed-chamber at Longwood. My two watches, and the chain of the Empress’s hair. I entrust the care of these articles to Marchand, my principal valet-de-chambre, and direct him to convey them to my son when he shall attain the age of sixteen years.

IV

My cabinet of medals. My plate, and my Sevres china, which I used at St. Helena. (List B. and C.): I request Count Montholon to take care of these articles and to convey them to my son when he shall attain the age of sixteen years.

V

My three saddles and bridles, my spurs which I used at St. Helena. My fowling-pieces, to the number of five: I charge my chasseur, Noverraz, with the care of these articles, and direct him to convey them to my son when he shall attain the age of sixteen years.

VI

Four hundred volumes, selected from those in my library of which I have been accustomed to use the most: I direct St. Denis to take care of them, and to convey them to my son when he shall attain the age of sixteen years.

NAPOLEON

List (B). / Inventory of the Effects which I left in the possession of Monsieur the Count de Turenne.

List (B).

Inventory of the Effects which I left in the possession of Monsieur the Count de Turenne.

One Sabre of Sobiesky.

One Grand Collar of the Legion of Honour. One sword of silver-gilt. One Consular sword. One sword of steel. One velvet belt. One Collar of the Golden Fleece. One small dressing-case of steel. One night-lamp of silver. One handle of an antique sabre. One hat à la Henry IV. and a toque. The lace of the Emperor. One small cabinet of medals. Two Turkish carpets. Two mantles of crimson velvet, embroidered, with vests, and small-clothes.

I give to my Son the sabre of Sobiesky, the collar of the Legion of Honour, the sword silver gilt, the Consular Sword, the steel sword, the collar of the Golden Fleece, the hat à la Henry IV. and the toque, the golden dressing-case for the teeth, which is in the hands of the dentist.

I give to the Empress Marie-Louise, my lace.

To Madame, the silver night-lamp.

To the Cardinal, the small steel dressing-case.

To Prince Eugene, the wax-candle-stick, silver gilt.

To the Princess Pauline, the small cabinet of medals.

To the Queen of Naples, a small Turkish carpet.

To the Queen Hortense, a small Turkish carpet.

To Prince Jerome, the handle of the antique sabre.

To Prince Joseph, an embroidered mantle, vest, and small-clothes.

To Prince Lucien, an embroidered mantle, vest, and small-clothes.

NAPOLEON

This 16th April, 1821, Longwood. / This is my Codicil or act of my last Will.

This 16th April, 1821, Longwood.

This is my Codicil or act of my last Will.

1. It is my wish that my ashes may repose on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people, whom I have loved so well.

2. I bequeath to counts Bertrand and Montholon and to Marchand, the silver, jewels, plate, porcelain, furniture, books, arms, etc. and in general everywhich I owned on St Helena

This present codicil, wholly written with my own hand, is signed and sealed with my own arms.

NAPOLEON

This 16th April, 1821, Longwood. / This is a second Codicil or act of my last Will.

This 16th April, 1821, Longwood.

This is a second Codicil or act of my last Will.

By my first codicil, dated today, I bequeathed all which I owned on St Helena to counts Betrand and Montholon and to Marchand. This is a stratagem in order to keep the British out of my succession. My will is that my effects should be disposed of in the following manner:

1. I have 300,000 francs in gold and silver, 30,000 francs of which should be set asied to pay the domestics. The rest should be distributed as follows: 50,000 to Bertrand; 50,000 to Montholon; 50,000 to Marchand; 15,000 to Saint-Denis; 15,000 to Noverraz; 15,000 to Pierron; 15,000 to Vignali; 10,000 to Archambault; 10,000 to Coursot; 5,000 to Chandellier. The rest should be given in gratifications to the British doctors, the Chinese domestics and the parish cantor.

2. I bequeath to Marchand my diamond necklace

3. I bequeath to my son all the effects which I used daily, according to the List A, here adjoined.

4. All the rest of my effects should be divided up between Bertrand and Montholon, Marchand, forbidding anything used for my body to be sold.

5. I bequeath to Madame, my good and dear mother, the busts, large paintings, and small paintings in my chambers, and the sixteen eagles. These she should distribute between my brothers, sisters and nephews (I charge Coursot to carry these opbjects to Rome); as for the Chinese collars and chains, Marchand is to give them to Pauline.

6. All the gifts listed in this codicil are independent of those made in my will.

7. My will should be opened in Europe, in the presence of those who have signed on the envelope.

8. I institute my executors as the Counts Montholon and Bertrand and Marchand.

This present codicil, wholly written with my own hand, is signed and sealed with my own arms.

On the envelope is written:

This is a second codicil, wholly written with my own hand.

This 24th of April. 1821, Longwood. / This is my Codicil, or note of my last Will.

This 24th of April. 1821, Longwood.

This is my Codicil, or note of my last Will.

Out of the settlement of my civil list of Italy, such as money, jewels, plate, linen, equipages, of which the Viceroy is the depositary, and which belong to me, I dispose of two millions, which I bequeath to my most faithful servants. I hope that, without availing himself of any reason to the contrary, my son Eugene Napoleon will pay them faithfully. He cannot forget the forty millions which I gave him in Italy, and in the distribution of the inheritance of his mother.

1. Out of these two millions, I bequeath to Count Bertrand three hundred thousand francs, of which he will deposit one hundred thousand in the treasurer’s chest, to be disposed of according to my dispositions in payment of legacies of conscience.

2. To Count Montholon, two hundred thousand francs, of which he will deposit one hundred thousand in the chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

3. To Count Las Cases, two hundred thousand francs, of which he will deposit one hundred thousand in the chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

4. To Marchand, one hundred thousand francs, of which he will deposit fifty thousand in the chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

5. To Count Lavalette, one hundred thousand francs.

6. To General Hogendorp, of Holland, my aide-de-camp, who has retired to the Brazils, one hundred thousand francs.

7. To my aide-de-camp, Corbineau, fifty thousand francs.

8. To my aide-de-camp, General Caffarelli, fifty thousand francs.

9. To my aide-de-camp, Dejean, fifty thousand francs.

10. To Percy, surgeon-in-chief at Waterloo, fifty thousand francs.

11. Fifty thousand francs; that is to say:–

Ten thousand to Pierron, my maître d’hôtel. Ten thousand to St. Denis, my head chasseur. Ten thousand to Noverraz. Ten thousand to Coursot, my clerk of the kitchen. Ten thousand to Archambault, my piqueur.

12. To Baron Méneval, fifty thousand francs.

13. To the Duke d’Istria, son of Bessières, fifty thousand francs.

14. To the daughter of Duroc, fifty thousand francs.

15. To the children of Labedoyère, fifty thousand francs.

16. To the children of Mouton-Duvernet, fifty thousand francs.

17. To the children of the brave and virtuous General Travot, fifty thousand francs.

18. To the children of Chartrand, fifty thousand francs.

19. To General Cambronne, fifty thousand francs.

20. To General Lefebvre-Desnouettes, fifty thousand francs.

21. To be distributed amongst such proscribed persons as wander in foreign countries, whether they be French, Italian, Belgians, Dutch, Spanish, or inhabitants of the departments of the Rhine, under the directions of my executors, and upon their orders, one hundred thousand francs.

22. To be distributed amongst those who suffered amputation or were severely wounded at Lingy or Waterloo, who may be still living, according to lists drawn up by my executors, to whom shall be added Cambronne, Larrey, Percy, and Emmery. The guard shall be paid double; those of the Island of Elba, quadruple; two hundred thousand francs.

This codicil is written entirely with my own hand, signed, and sealed with my arms.

NAPOLEON

On the envelope is written:

This is my codicil, or note of my last Will. I recommend that my son Eugène enact precisely what is written here. It is wholly written with my own hand.

This 24th of April, 1821, at Longwood. / This is my third Codicil to my Will of the 15th of April.

This 24th of April, 1821, at Longwood.

This is my third Codicil to my Will of the 15th of April.

1. Amongst the diamonds of the Crown which were delivered up in 1814, there were some to the value of five or six hundred thousand francs, not belonging to it but which formed part of my private property; repossession shall be obtained of them in order to discharge my legacies.

2. I had in the hands of the banker Torlonia, at Rome, bills of exchange to the amount of two or three hundred thousand francs the product of my revenues of the Island of Elba since 1815. The Sieur Peyrusse, although no longer my treasurer, and not invested with any character, possessed himself of this sum. He shall be compelled to refund it.

3. I bequeath the Duke of Istria three hundred thousand francs of which only one hundred thousand francs shall be reversible to his widow, should the Duke be dead before payment of the legacy. It is my wish, should there be no inconvenience in it, that the Duke may marry Duroc’s daughter.

4. I bequeath to the Duchess of Frioul, the daughter of Duroc, two hundred thousand francs: should she be dead before the payment of this legacy, none of it shall be given to the mother.

5. I bequeath to General Rigaud, (to him who was proscribed) one hundred thousand francs.

6. I bequeath to Boinod, the intendant commissary, one hundred thousand francs.

7. I bequeath to the children of General Letort, who was killed in the campaign of 1815, one hundred thousand francs.

8. These eight hundred thousand francs of legacies shall be considered as inserted at the end of Article thirty-six of my testament, which will make the legacies I have disposed of by will amount to the sum of six million four hundred thousand francs, without including the donations I have made by my second codicil.

This is written with my own hand, signed, and sealed with my arms.

(Seal)

NAPOLEON

On the envelope is written:

This is my third codicil to my will, entirely written with my own hand, signed, and sealed with my arms. To be opened the same day, and immediately after the opening of my will.

NAPOLEON

This 24th of April, 1821. Longwood. / This is a fourth Codicil to my Testament.

This 24th of April, 1821. Longwood.

This is a fourth Codicil to my Testament.

l. We bequeath to the son or grandson of Baron Du Teil, lieutenant-general of artillery, and formerly lord of St. André, who commanded the school of Auxonne before the Revolution, the sum of one hundred thousand francs, as a memento of gratitude for the care which that brave general took of us when we were lieutenant and captain under his orders.

2. Idem, to the son or grandson of General Dugommier, who commanded in chief the army of Toulon, the sum of one hundred thousand francs. We, under his orders, directed that siege, and commanded the artillery: it is a testimonial of remembrance for the marks of esteem, affection, and friendship, which that brave and intrepid general gave us.

3. Idem, We bequeath one hundred thousand francs to the son or grandson of the deputy of the Convention, Gasparin, representative of the people at the army of Toulon, for having protected and sanctioned with his authority the plan we had given, which procured the capture of that city, and which was contrary to that sent by the Committee of Public Safety. Gasparin, by his protection, sheltered us from the persecution and ignorance of the general officers who commanded the army before the arrival of my friend Dugommier.

4. Idem, We bequeath one hundred thousand francs to the widow, son, or grandson, of our aide-de-camp Muiron, killed at our side at Arcole, covering us with his body.

5. Idem, Ten thousand francs to the subaltern officer Cantillon, who has undergone a trial upon the charge of having endeavoured to assassinate Lord Wellington, of which he was pronounced innocent. Cantillon has as much right to assassinate that oligarchist as the latter had to send me to perish upon the rock of St. Helena. Wellington, who proposed this outrage, attempted to justify it by pleading the interest of Great Britain. Cantillon, if he had really assassinated that lord, would have pleaded the same excuse, and been justified by the same motive–the interest of France–to get rid of this General, who, moreover, by violating the capitulation of Paris, had rendered himself responsible for the blood of the martyrs Ney, Labédoyère, &c.: and for the crime of having pillaged the museums, contrary to the text of the treaties.

6. These four hundred an ten thousand francs shall be added to the six million for hundred thousand of which we have disposed, and will make our legacies amount to six million eight hundred and ten thousand francs; these four hundred and ten thousand are to be considered as forming part of our testament, Article 36, and to follow in every respect the same course as the other legacies.

7. The nine thousand pounds sterling which we gave to Count and Countess Montholon, should, if they have been paid, be deducted and carried to the account of the legacies which we have given him by our testament. If they have not been paid, our notes of hand shall be annulled.

8. In consideration of the legacy given by our will to Count Montholon, the pension of twenty thousand francs granted to his wife is annulled. Count Montholon is charged with the payment of it to her.

9. The administration of such an inheritance, until its final liquidation, requiring expenses of offices, journeys, missions, consultations, and lawsuits, we expect that our testamentary executors shall retain 3 per cent. upon all the legacies, as well upon the six million eight hundred thousand francs, as upon the sums contained in the codicils, and upon the two hundred millions of francs of the private domain.

10. The amount of the sums thus retained shall be deposited in the hands of a treasurer, and disbursed by drafts from our testamentary executors.

11. Should the sums arising from the aforesaid deductions not be sufficient to defray the expenses, provisions shall be made to that effect at the expense of the three testamentary executors and the treasurer, each in proportion to the legacy which we have bequeathed to them in our will and codicils.

12. Should the sums arising from the before-mentioned subtractions be more than necessary, the surplus shall be divided amongst our three testamentary executors and the treasurer, in the proportion of their respective legacies.

13. We nominate Count Las Cases, and in default of him his son, and in default of the latter, General Drouot, to be treasurer.

This present codicil is entirely written with our hand, signed, and sealed with our arms.

NAPOLEON

This 24th April, 1821, Longwood. / This is my Codicil or act of my last Will.

This 24th April, 1821, Longwood.

This is my Codicil or act of my last Will.

Upon the funds remitted in gold to the Empress Maria Louisa, my very dear and well-beloved spouse, at Orleans, in 1814, she remains in my debt two millions, of which I dispose by the present Codicil, for the purpose of recompensing my most faithful servants, whom moreover I recommend to the protection of my dear Maria Louisa.

1. I recommend to the Empress to cause the income of thirty thousand francs, which Count Bertrand possessed in the Duchy of Parma, and upon the Mont Napoleon at Milan, to be restored to him, as well as the arrears due.

2. I make the same recommendation to her with regard to the Duke of Istria, Duroc’s daughter, and others of my servants who have continued faithful to me, and who have never ceased to be dear to me: she knows them.

3. Out of the above-mentioned two millions I bequeath three hundred thousand francs to Count Bertrand, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer’s chest to be employed in legacies of conscience, according to my dispositions.

4. I bequeath two hundred thousand francs to Count Montholon, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer’s chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

5. Idem, two hundred thousand francs to Count Las Cases, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer’s chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

6. Idem, to Marchand one hundred thousand francs, of which he will place fifty thousand in the treasurer’s chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

7. To Jean Jerome Levy, the Mayor of Ajaccio at the commencement of the Revolution, or to his widow, children, or grand-children, one hundred thousand francs.

8. To Duroc’s daughter, one hundred thousand francs.

9. To the son of Bessières, Duke of Istria, one hundred thousand francs.

10. To General Drouot, one hundred thousand francs.

11. To Count Lavalette, one hundred thousand francs.

12. Idem, one hundred thousand francs; that is to say:–

Twenty-five thousand to Pierron, my maître d’hôtel. Twenty-five thousand to Novarre, my chasseur. Twenty-five thousand to St. Denis, the keeper of my books. Twenty-five thousand to Santini, my former door-keeper.

13. Idem, one hundred thousand francs; that is to say:–

Forty thousand to Planat, my orderly officer. Twenty thousand to Hébert, lately house-keeper of Rambouillet, and who belonged to my chamber in Egypt. Twenty thousand to Lavigné, who was lately keeper of one of my stables, and who was my piqueur in Egypt. Twenty thousand to Jeannet-Dervieux, who was overseer of the stables, and served me in Egypt.

14. Two hundred thousand francs shall be distributed in alms to the inhabitants of Brienne-le-Château, who have suffered most.

15. The three hundred thousand francs remaining shall be distributed to the officers and soldiers of the battalion of my guard at the Island of Elba who may be now alive, or to their widows and children, in proportion to their appointments, and according to an estimate which shall be fixed by my testamentary executors: those who have suffered amputation, or have been severely wounded, shall receive double; the estimate to be fixed by Larrey and Emmery.

This codicil is written entirely with my own hand, signed, and sealed with my arms.

NAPOLEON

[On the envelope is written]:

This is my codicil, or note of my last Will. I recommend that my dear wife, the Empress Marie-Louise, enact what is written here.