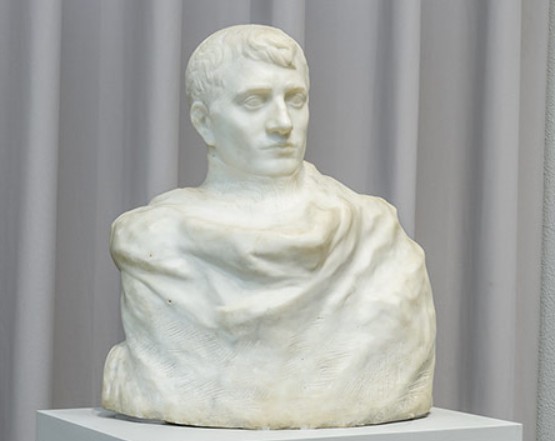

This posthumous portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte carved in marble must be one of the most curious works to come out of the studio of French sculptor Auguste Rodin. It was commissioned in 1904 by the American collector Kate Seney Simpson,The daughter of a Brooklyn banker and art collector, George I. Seney and wife of New York lawyer, John Woodruff Simpson. Mrs Simpson was not only an enthusiastic patron of Rodin, she was also instrumental in encouraging the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to invest in the work of the French artist during his lifetime, as well as donating work by Rodin from her own collection. For more on the history of that museum’s Rodin Collection see “Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a history of the collection” by Claire Vincent one of several American patrons of the famous French sculptor. Rodin had already modelled a portrait of the wealthy Mrs Simpson in the year 1902 (the marble version was exhibited in 1904), illustration page 22 in “Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a history of the collection” by Claire Vincent. and from 1903, she began to acquire a number of works by Rodin, mostly pre-existing works from his studio or re-editions (such as “The Thinker”, “Saint John at the Column”, “the Centauresse”, and heads of Balzac). It is unclear what inspired the commission for a portrait of the French Emperor, though it may not be entirely coincidental that the commission was made in the year 1904, exactly a hundred years after Napoleon’s “Sacre” (his coronation and consecration by the Pope).

A ‘prototype’

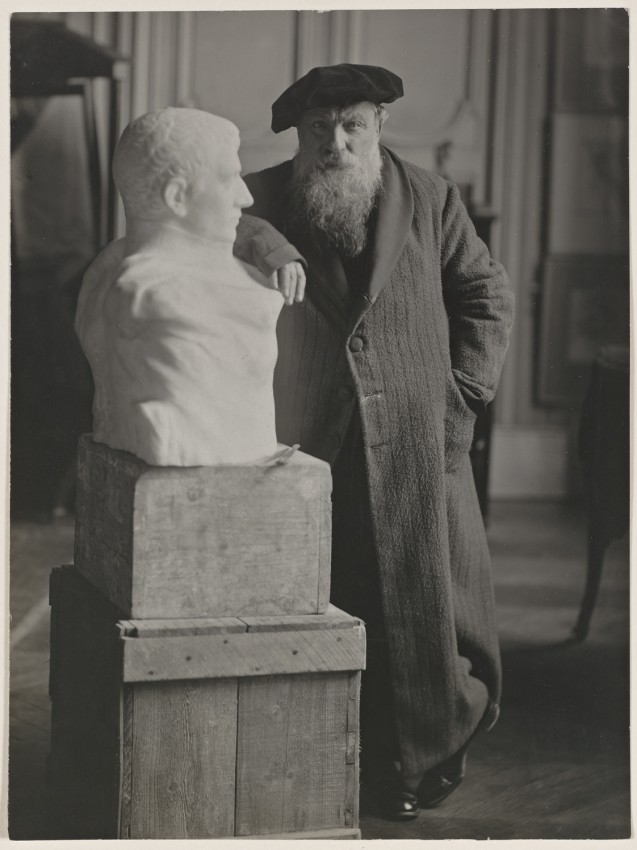

For all of his sculptures, whether nudes or portraits, Rodin would begin by making several studies in clay before he was ready to have it realised in the definitive material whether bronze or, in this case, marble. A study for this bust of Napoleon made of plaster is preserved at the Musée Rodin (France), which appears to be a cast of a clay model. It has been suggested that Rodin took inspiration for the face of Napoleon from a copy of an “Antommarchi” Napoleon death mask which he owned, however, it seems quite likely, given the artist’s usual method of working from live models, that in the absence of the authentic subject, he may have hired a look-alike. We know that Rodin had done just this for the realisation of another posthumous portrait, that of Honoré Balzac, for which the sculptor had made several trips to the French town of Tours in order to find models with the same rugged morphology as his illustrious subject.see illustration and caption on page 18 and 19, “Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a history of the collection” by Claire Vincent. One of Rodin’s assistants, the sculptor Alfred Jean Halou, was thought to bear a striking resemblance to the First French Emperor. Using a pantographTraces of the pantograph can be seen on the marble sculpture, the precise coordinates of the final prototype would be first transferred onto the marble block which was to be sculpted,The marble of this bust has been identified as Carrara marble (which corresponds to an order made for that material by Rodin in the year 1904) and the actual carving of the marble would be carried out by skilled assistants, known as “practicians”, according to the master’s instructions with the help of the maquette. This marble was realised by that very same assistant Halou [1875-1939] and another sculptor, Ernest Nivet [1871-1948].

Representing the Emperor

The existence of the surviving plaster study gives us not only an insight into Rodin’s working methods, but also provides a glimpse into the evolution of Rodin’s ideas for how to represent the French Emperor. Compared to the finished marble sculpture, the earlier bust is a much more objective study of a human form, the face, hair and upper torso are modelled with attention to detail. On the front, below the large swathe of “drapery” reminiscent of many antique portraits, we can distinguish the recognisable shapes of Napoleon’s favourite outfit – the chasseur colonel uniform with the red sash and the buttoned waistcoat – (which may have been copied from a painting). Just like for his Balzac statue, Rodin appears, here too, to have dressed up his naked clay prototype with different outfits before deciding on his final version.

In the marble version of Rodin’s Napoleon, the elements of “contemporary” dress have been almost entirely eliminated; indeed the torso is completely submerged up to the neck in the block of marble whose treatment suggests a cloak or cape such as those worn by military leaders in Roman times and especially Emperors,After the reign of Augustus, this type of garment known as a Paludamentum was restricted to Emperors. yet at the same time evokes a sort of ethereal cloud; only the head appears to emerge from the high collar, bearing traces of embroidery, but which, unlike the earlier version, now covers the entire neck and merges with the marble mass. Another noticeable difference in the final version is that the facial expression is less severe and more meditative, even vague, indeed the title inscribed on the base is “Napoleon enveloppé dans son rêve” (“Napoleon wrapped in his dream”). The overall effect of the 350-kilogramme marble is something more timeless, vaguely reminiscent of a classical bust of a Roman Emperor, even in the treatment of the hair (clearly seen in the photo with Rodin, below). Are we therefore to see in Rodin’s work, a Napoléon immersed – even submerged – in a “dream”, possibly a yearning for classical Empire?

The bust was not finished until around 1909. It was not, finally, Mrs Simpson who acquired the work but a friend of hers, another collector, the self-made millionaire Thomas Fortune Ryan,For a portrait of Thomas Ryan, modelled from life in 1909 by Rodin, see page 32-34 “Rodin at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a history of the collection” by Claire Vincent who bought it whilst on a visit to Rodin’s Meudon studio in 1909.At the same time Ryan acquired a number of other works by the artist.

From 1912 to 1929, the work went on public display when Ryan loaned the work to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.The Museum’s Board of Trustees, encouraged by Mrs Simpson and through the patronage of Thomas Ryan, had already established a substantial collection of Rodin’s works during the artist’s lifetime.When Ryan died in 1928, the bust of Napoleon was sold off (the sale took place in 1933) and bought by Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, who deposited it at the Hartley Dodge Memorial building in Madison, New Jersey, built in memory of her son who had died in a car accident in 1930 and which served as a local borough hall. Years passed and, as Napoleon silently presided over the various meetings from atop of his dreamy marble cloud, extraordinarily the sculpture’s identity (despite being signed by the world-famous “A Rodin” and inscribed with the name of the First French Emperor) was progressively forgotten. It was only in 2015, during an inventory of the Hartley Dodge Foundation collection by art history student Mallory Mortillaro, that the portrait was recognized as a work of Rodin, an identification later confirmed by Rodin expert Jérôme Le Blay. The discovery was brought to public attention in October 2017,https://www.napoleon.org/en/magazine/press-review/sculpture-napoleon-rodin-discovered-new-jersey-town-hall/ and shortly after, in November 2017, on the 100th anniversary of Rodin’s death, the sculpture was reunited with other works from the artist’s studio at the Philadelphia Museum of Art,https://press.philamuseum.org/museum-honors-100-years-of-rodin/ where it will remain on a long-term loan.

Rebecca Young, December 2017