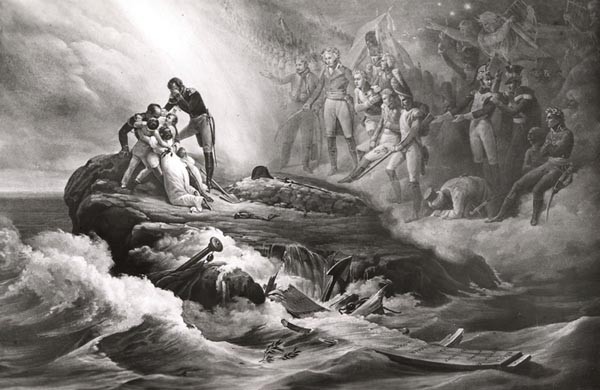

Geometrically this composition is formed by a succession of roughly parallel diagonals (each of which dissects the painting descending from left to right) intersected by a central perpendicular diagonal (from bottom left to top right) as well as several smaller ones in the same direction.

On the bottom left of the scene, a slash of white foam crashes against a dark shadowy rock, in front of which can be seen the remains of a mast, a sail, an anchor and a section of shipwreck bearing inscriptions. On the top right of the composition, looking down onto the rock, stands a group of officers (some dressed as mamluks) positioned on a pale cloud (which echoes the wave motif in the opposite corner). Behind these men legions of ghostly, heroic “grognards” stretch into the distance whilst mythological figures float above playing harps.

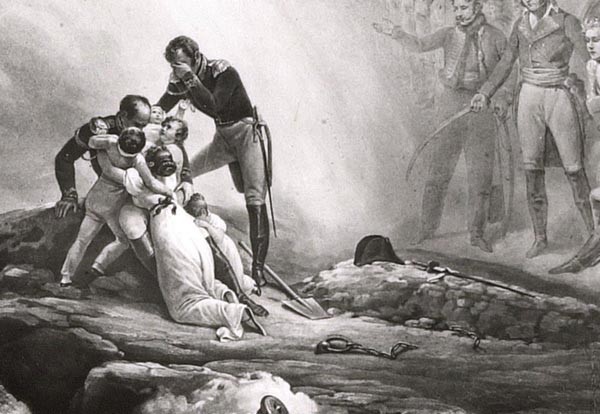

As if to distinguish between the earthy and celestial worlds, a column of light appears to burst through the clouds dividing Vernet’s painting into two triangles and illuminating a freshly-dug, rudimentary grave that occupies the centre of the composition and upon which rest Napoleon’s bicorn and his sword. Immediately to the left, a group of mourners, overcome by emotion, have just buried their master. We recognise them as Napoleon’s companions-in-exile, General Charles-Tristan Montholon (1783-1853) standing over General Henri-Gatien Bertrand (1773-1844) sitting on a piece of rock. In front of Bertrand, almost prostrate, is his wife Fanny (1785-1836) clutching their four children (including Arthur, who was born on St Helena in 1817).

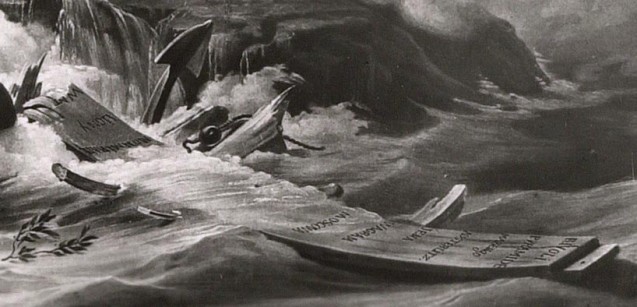

Emerging from the tomb, a chain formerly welded to the rock has been rent in two, thus symbolising the end of Napoleon’s exile and captivity: Napoleon the legend, the myth, liberated from the confines of this earthly prison, can now unfold. But for now, all that survives this “shipwreck” are a small branch of laurels and the names of the glorious battles inscribed on a plank of wood still afloat: Rivoli, Pyramides, Marengo, Austerlitz, Iéna, Wagram, Moscowa, Montmirail,[…] Ligny, and finally Wat[erloo], (the latter is truncated by the splintered wood).

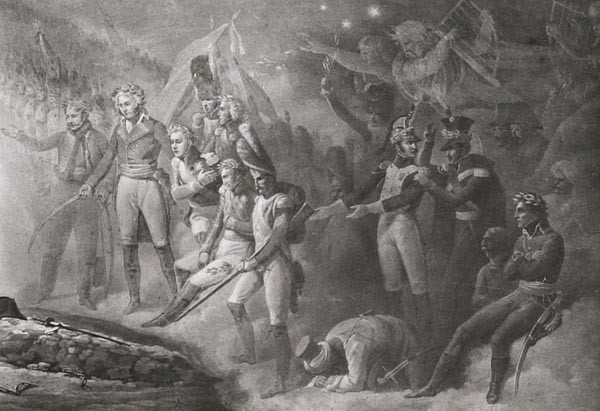

It is more difficult to identify the ethereal group of officers, wearing laurel wreaths, on the right of the painting, paying homage to the dead Emperor. From left to right, we have possibly the “hussar general” Antoine de Lasalle, with his right hand raised (1775-1809, who died at Wagram), General Jean-Baptiste Kléber (1753-1800, assassinated in Cairo), Marshal Jean Lannes with his right hand on his heart (1769-1809, who died of his wounds on the island of Lobau, shortly after the battle of Essling), behind him Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières (1768-1813, killed by a cannonball in Rippach, the day before the battle of Lützen). Further to the right could be Marshal Joseph Antoine Poniatowski, with his arms raised (1763-1813, killed at the battle of Leipzig). On the far right, the seated figure could be a representation of General Bonaparte himself, watching the fulfilment of his destiny.

A replica of the original painting (below), made by Vernet in October 1821 with some variations, is kept at the Wallace Collection in London (see zoomable HD version). Its first identified owner was the banker Jacques Laffitte (1767-1844) who acquired it on 26 October 1821(according to the Wallace Collection website).

This is a version of an article in French by Irène Delage (February 2021), with additions by Rebecca Young (November 2021).