This portrait of the Countess of Castiglione has become emblematic of the history of photographic art and more specifically of self-portraiture. The personality of its subject, “la Castiglione”, has contributed to its fascination, which has not diminished over the years, continuing to inspire a multitude of questions and hypotheses as to the reasons for the forty-year photographic adventure of which this print is just one element.

Virginia Oldoïni, Countess Verasis of Castiglione (1837-1899)

Virginia Oldoïni was born in 1837 (she herself claimed her year of birth to be 1843) into a Genoese aristocratic family on her father’s side and Florentine by her mother. From her early teens she was admired for her great beauty. Her destiny was well mapped out: a wealthy marriage (in 1854, to Francesco Verasis, Count of Castiglione), motherhood at the age of 18 (her only son, Giorgio, was born in 1855), and a rich social life. In November 1855, the Countess, who was a relative of the President of the Italian Consiglio, Camillo Cavour, met discreetly with King Victor-Emmanuel. During this meeting she agreed to try to persuade Napoleon III to support Italy’s unification and rejection of the Austrian in presence in the peninsula: this issue was to be discussed at the 1856 Paris Congress. In what can only be described as a charm offensive, the Countess settled in Paris with her husband and their son on Christmas Day 1855. She took the city by storm with her appearances at social gatherings, wearing extravagant outfits designed like theatre costumes, and became Napoleon III’s mistress for two years. But on the night of 5 to 6 April 1857, the Emperor was attacked by three carbonari as he was leaving his lover’s home on the Avenue Montaigne. Despite having nothing to do with the ambush, Virginia de Castiglione was ordered to leave Paris for a while; which she did for a month or so. On her return to the social round of Parisian balls and receptions, however, she discovered that the Emperor had moved on to a new mistress.

Tired of his wife’s behaviour, and almost ruined by her extravagant lifestyle, the Count of Castiglione obtained a separation from his wife in 1857, who was only twenty years old at the time. After living for a time in London, then near Turin (Italy), Virginia de Castiglione returned to Paris in 1861, and settled in the neighbourhood of Passy until the fall of the Empire and the institution of the Paris Commune, whereupon she moved to Italy for two years, returning to Paris, this time to Place Vendôme, in 1872. Over the years, she had cultivated various chivalrous friendships and remained close to the political world. Solicited by Thiers in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian negotiations, she went on a mission to Bismarck, with whom she was already acquainted.

Suffering from depression, Virginia de Castiglione gradually withdrew into a life of reclusiveness marked by attacks of madness, and became a patient of the psychiatrist Dr Blanche. The death of her son Giorgio in 1879, at the age of 24, further aggravated her mental health. She died in 1899 in Paris, and was buried in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise.

A collaboration lasting more than forty years with the photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson

The Countess of Castiglione would appear to have been obsessed with her own image since she had herself photographed during a period of over forty years by Pierre-Louis Pierson (1822-1913), the first photo being taken in July 1856, the last in 1895.

Before 1861, 55 portraits were made, of which 34 were by Pierson. Between 1861 and 1867 and between 1875 and 1895, Pierson made another 289 portraits of her, as well as 110 photographs of her son, and 5 of her dogs (figures quoted by Nicole G. Albert, in La Castiglione, Perrin, p.95). This extraordinary mass of portraits that filled the Countess’ apartments was not at the time intended to be exhibited but simply viewed by a chosen few.

As for the photographer, Pierre-Louis PiAll Itemserson, he had come to Paris from the Moselle region of France in 1844, and in 1855 (already an experienced photographer) he entered into a partnership with the brothers Léopold Ernest and Louis Frédéric Mayer, the studio at 5 Boulevard des Capucines becoming known as the “Maison Mayer Frères et Pierson”. In 1863, Pierson bought out the Mayers but kept the name “Mayer et Pierson”. Throughout the decade, the “Maison Mayer et Pierson” was very well-known and included among its clients not only Emperor Napoleon III (see a photo of the Prince Imperial), but also the King of Württemberg, the Queen of the Netherlands, the King of Portugal, and the King of Norway and Sweden. From 1878, Pierson went into association with his son-in-law, Gaston Braun and the latter’s partner Léon Clément, joining the “Maison Adolphe Braun et compagnie”, which then became known as the “Maison Braun, Clément et compagnie” in 1889.

With his perfect handling of his technique, as well as his patient acceptance of all the demands of his client, Pierson proved to be the ideal collaborator for “La Castiglione”. Whilst the first photos were classic both in their compositions and the outfits worn, the Countess went on to increase the number of portraits, varying the sets, the staging and the outfits, even disguises. Indeed, her input was so extensive that these photographs ought more properly to be considered as auto-portraiture albeit with the collaboration of a skilled photographer.

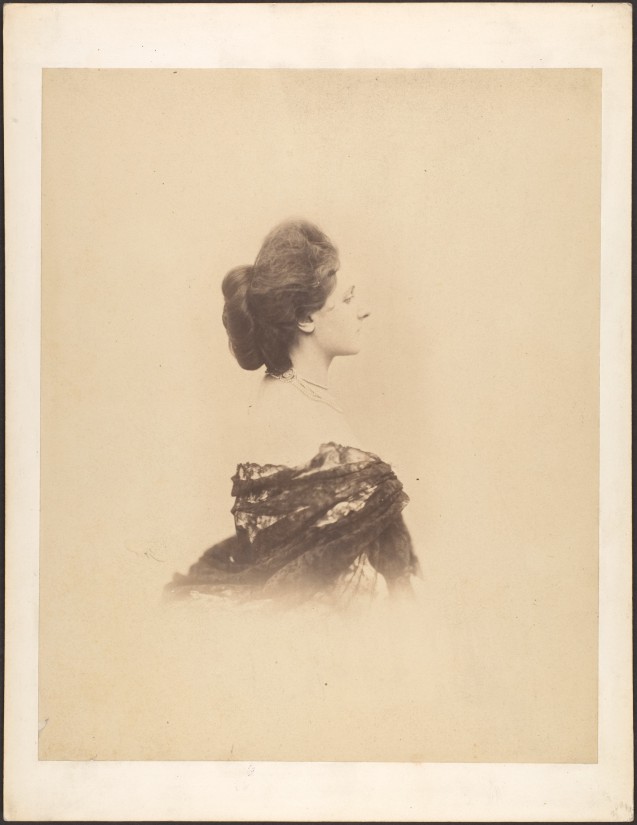

this dress was worn in 1857) by Pierre-Louis Pierson, circa 1861-1863

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA

Furthermore, the Countess’ shots would frequently be ‘storied’ and have added colour, a practice much appreciated at the time. For example, on the back of the print of the colour-enhanced photo entitled “La Frayeur” [“The Fright”] – the titles were mostly chosen by the Countess herself – she noted a scenario as well as corrections to be made to the print: “The debris from a fire at a ball. A chandelier on the floor, everyone running away. White satin dress, shiny, black and red grapes, with dark green and red leaves. Remove the hair ball at temple of the neck; replace with vine; same finished movement, right, top; cover all the right side of the hair with the background colour.” (quoted by Nicole G. Albert, La Castiglione, Perrin, p.149).

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA

These photographs are experiments in boldness and extravagance. The poses and framing, always defined by the Countess, went beyond demonstrations of outfits, with, for example, some photos of close-ups of her arms, legs or feet, as early as the 1860s, then in the 1890s. Women from the Countess’ social background certainly did not have pictures taken of themselves in these postures which would have been considered indecent at the time. Thus, whilst these experiments are not innovative from the point of view of general photographic practice at the time, they remain exceptional for a woman of the Countess’ rank, especially considering she was the initiator, inspired by photos produced elsewhere, such as photos of dancers.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA

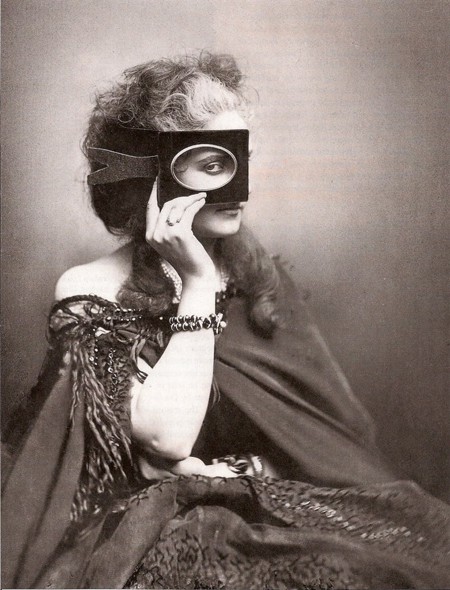

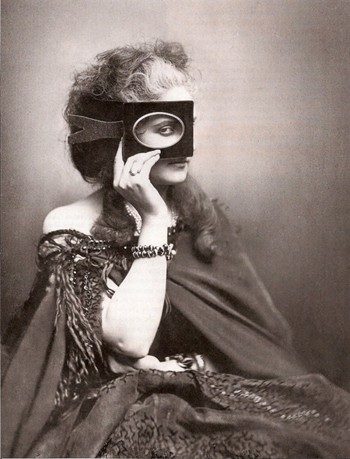

Scherzo di Follia

by Pierre-Louis Pierson, circa 1863-1866

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA

In “Scherzo di Follia” (“Joke Madness”), made sometime between 1863 and 1866, the Countess hides part of her face, in semi-profile, with a picture frame held in her right hand, through which she stares at the viewer. She wears a kind of tunic or cape, leaving her shoulders bare; her left shoulder is hidden by her hair. There is play on the idea of “looking”. It is as if she is saying: I see you looking at me, looking at my bare shoulder, but, by partially hiding my face from you, I am not giving myself in full to your gaze; and indeed, with my face concealed, are you sure it is really me you’re looking at? However, it is difficult to decipher the exact expression of the gaze: it seems empty rather than blasé or questioning. The long exposure time required for studio photographs in those days had the effect of modifying any original intended expression of an emotion. It is thus risky to attempt to attribute meaning to this so-called “joke madness”, or to define it as exhibitionism, dissimulation, or even feminism. That being said, the Countess did refuse to be confined by the position that society attributed to her (that of obedient wife and mother which she performed badly), or by the role that she was asked to play (ambassadress) to which she agreed to lend her body. In the end, all we can say is that her photographic obsession would appear to have been motivated entirely by her own desire for emancipation in the service of her image.

Given the sheer number and variety (see a set of photos on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), the extreme care taken in the choice of clothes and accessories (prefiguring the art of fashion photography), the punctilious staging, and the great duration of the process, it is clear that the photos of the Countess of Castiglione are the result of a thoughtful artistic perspective: a production decided by a woman, choosing herself as a subject, staging her social attributes as well as her imagination, constantly experimenting. Indeed, we know that she wanted to be considered as the author of her photos. In 1867, when her portrait as “Lady of Hearts” was shown at the Paris Universal Exhibition, together with other photos by the Maison Mayer et Pierson, she hoped, in vain, to be given an exhibitor’s ticket: the Count of Nieuwerkerke, Superintendent of Fine Arts, could not grant her request because “they are only given to the photographer. Mr. Le Play, Commissioner General, is not accommodating, and if I had insisted, I would have compromised your anonymity.” (quoted in La comtesse de Castiglione par elle-même, notice 98, p. 186).

In the last year of her life, Virginia de Castiglione tried to organise an exhibition of her portraits, entitled The most beautiful woman of her century, telling the story of the forty years she had spent inventing (in the controlled setting of the photographic studio) a parallel life intended for posterity, immortalising her beauty and controlling her image, even in her final years marked by decline and disease.

The photographic work of the Countess of Castiglione continues to fascinate, provoke and inspire artists. It is the narcissistic expression of a remarkable personality of the second half of the 19th century, which still today provokes reflection on the definition of identity, the status of the body both intimate and social, and the boundaries between the real and the virtual.

Irène Delage, October 2018 (translation RY)

Find out more:

- Collection of photos on the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- La comtesse de Castiglione par elle-même, exhibition catalogue, Musée d’Orsay, 1999

- Federica Muzzarelli, Femmes photographes. Émancipation et performance 1850-1940, Hazan, 2009

- Nicole G. Albert, La Castiglione. Vies et métamorphoses, Perrin, 2011

- Beatrice Piantanida, “Dalla Contessa di Castiglione a Lady Gaga. Dalla Musa all’Icona nella storia della fotografia [From the Countess of Castiglione to Lady Gaga. From the muse to the icon in photography’s history]. Figure. 1-2013, 10.6092/issn.2038-6184/4087.