On 17 July 1870, as tensions rose between France and Prussia, France declared war on Prussia. It did so on the grounds of the protocol conflict sparked by the Ems Dispatch, released by Bismarck, red rag to a bull for the French supporters of a war with Prussia.

On 2 June, the Prussian king and Bismarck obtained a secret promise from Czar Alexander II (1818-1881) that Russia would support Prussia if Austria were to back France in an armed conflict.

► Learn more about the march to the war of 1870

► Learn more about the Ems Dispatch

15 July > War appropriations were voted for by the Corps Législatif. Adolphe Thiers objected: ‘Vous n’êtes pas prêts, cette guerre que vous vous apprêtez à faire est une folie.’ [You are not ready, this war you are about to wage is utter madness]. His mansion was stoned later that night. Of the 32 republican deputies, 20 abstained from the vote. Thiers was the only one to oppose it in the four times the vote was tabled.

17 July > France declared war on Prussia (the official declaration was made on 19 July), Napoleon III took command of his military forces, with Marshal Le Boeuf as Major General. Pierre-Charles Dejean (1807-1872) served as Minister of War ad interim. Napoleon III’s health was failing although few knew the gravity of the situation, not even the Empress Eugenie. He was taking opium to relieve bouts of pain, and his physical shape was visibly altered.

20 July > Austria and Italy announced their neutrality. The finalisation of an alliance between France, Austria and Italy was a long way off when France declared war: the main obstacles were the desire for neutrality on the part of the majority of Austro-Hungarian public vis-à-vis Prussia, and the Roman question, which was being negotiated with Italy. France’s declaration of war only served to make these potential allies more reticent, and they ultimately decided to remain out of it altogether. On 5 August Russia confirmed that it would attack Austria if the latter attacked Prussia, which cemented Franz Joseph’s decision not to intervene.

23 July > Napoleon III’s proclamation to the French people. The Emperor explained that his reasons for pushing for a war, not against the German people but against Prussia, were to ensure the security of the Empire and its territory. He announced that he would be leaving with his son to lead the army at the front. ► Read a translation of the text of his proclamation

28 July > Despite the extremely poor state of his health, Napoleon III left the Palais de Saint-Cloud to join his headquarters at Metz and take charge of the Army of the Rhine. He was accompanied by the Prince Imperial, who was fourteen years of age. He meant for his son’s presence, as first in line to the imperial throne, to be a political act and symbol of strength. Napoleon III knew he was ill and had already sought the allegiance of the French people to the Prince Imperial with the Plebiscite of 8 May 1870. The Emperor intended to abdicate by the time the Prince came of age and the presence of the future Napoleon IV on the battlefields would ensure that his legitimacy was even more indisputable. The Empress Eugenie became regent of the Empire for the third time (she had already taken on the role in 1859 and 1865). She presided over the Ministerial Council, but was prohibited from promulgating any new laws, save for those already under discussion.

The French army comprised 343,000 men (265,000 men in the Army of the Rhine directly operational).Napoleon III hurriedly organised three grand armies at the beginning of July 1870, as he still believed that the Austrians would enter the war on the side of the French. On 1 July, each contingent was reduced from 100,000 to 90,000 men. The Gardes Mobiles were called upon to complete the numbers. Logistically, France lagged behind Prussia: it was taking longer to mobilise, and it lacked capable military leaders. The Major General, Le Boeuf, was a good example of this: when it came to artillery he was a genius, but had no knowledge whatsoever about the role of Major General. Under him, the generals distinguished themselves in colonial wars (for example in Algeria, Syria, and Mexico) which more often resembled guerrilla engagement rather than the strategic and tactical nature of the Prussian war at hand. It was another major disadvantage that the French Army did not have a map of eastern France.

As a result of conscription, the Prussian Army was able to raise 484,000 men and 50,000 horses immediately. It was very well trained and organised, and divided into three armies: the first was under the command of Steinmetz (in the west), the second under that of Prince Friedrich Karl (nephew of King Wilhelm and hero of Sadowa), and the third under the Kronprinz, facing Alsace. As well as the contribution of the armies of the North German Confederation, the Prussian Army was reinforced by troops from Bavaria,Würtemberg, Baden and Hesse.

1870 : The rapid collapse of the French Empire

2 August > The French troops launched an offensive on Saarbrücken. Despite their victory, the soldiers left the city after two days without destroying either the station or the bridges.

4 August > The first direct confrontation. The Prussians attacked the French at Wissembourg. The forces were unevenly matched: 7,000 French soldiers faced 70,000 Prussians. The French were defeated.

5 August > Russia announced that if Austria were to enter into the war against Prussia, it would attack Austria.

6 August > Marshal Patrice de MacMahon (1808-1893) led his troops at the Battle of Wörth, where they were routed. The French were also defeated at Reichshoffen (where one of the last cavalry charges in Western Europe took place) and at Forbach-Spicheren. At this point it was planned that French troops would withdraw to defend Paris. MacMahon admitted defeat and abandoned Alsace to the Prussians. Frossart abandoned Lorraine the same day.

7 August > After these first defeats, a state of siege was declared. Meanwhile, French Prime Minister Émile Ollivier (1825-1913) wanted Napoleon III to leave the front, but the Empress refused to support his request. The Republican deputies appealed to the citizens of Paris. Any potential allies were discouraged by the loss of France’s international prestige. The stock market, which had soared on 6 August, collapsed on 8 August.

10 August > Following the collapse of Émile Ollivier’s government on 9 August, a new government was appointed. It was to be led by General Cousin-Montauban, Comte de Palikao (1796-1878), who was also Minister of War. Godefroi, Prince de La Tour d’Auvergne-Lauraguais became Minister of Foreign Affairs; Chevreau, Minister of the Interior; Magne, Minister of Finance. Le Boeuf was dismissed. As a result of Republican pressure, Marshal François-Achille Bazaine (1811-1888) became commander in chief, seemingly as a last resort. After three battles he was taken prisoner at Metz between 14 and 16 August.

12 August > The Prussians entered Nancy, and Strasbourg prepared itself for a long siege. Napoleon III abandoned his command of the Army of the Rhine, leaving it to Marshal Bazaine, and reached Châlons on 14 August.

14-16 August > Inconclusive fighting at Borny, then between Mars-la-Tour and Gravelotte.

- Borny, 14 August: The Prussians lost in terms of occupation of the terrain and the number of men killed, and the French were able to retreat to Metz. However, it was a strategic victory for Wilhelm’s troops, as afterwards they were able to bring up reinforcements. Bazaine was not able to force the enemy into retreat.

- Mars-La-Tour, 16 August: The last great cavalry engagement, and one of the deadliest. 80,000 French troops faced 130,000 Prussians. There were 15,000 killed on both sides. Despite wining the encounter, Bazaine ordered the French retreat to Metz.

- Saint-Privat and Gravelotte, 18 August: 190,000 Prussians against 115,000 French troops. The bloody battle ended in a Prussian victory. The French retreat to Metz was now obligatory.

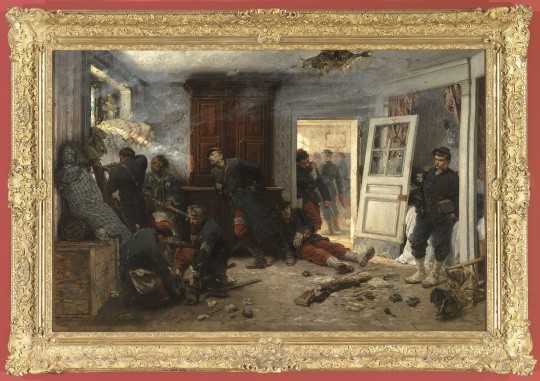

© RMN-Grand Palais – Agence Bulloz

18 August > General Louis Trochu (1815-1896) was appointed Governor of Paris, and the capital was to be protected by the Army of Châlons under the leadership of MacMahon. Napoleon III wanted to return to Paris, but the Empress Eugenie and Cousin-Montauban opposed the idea. Prussian victory at Gravelotte-Saint-Privat; with Bazaine’s retreat to Metz, the Prussians had cleared for themselves the way to Paris. A French alliance seemed less and less appealing to the Austrians.

23 August > Meanwhile, MacMahon and Napoleon III were at the military camp of Châlons preparing to march towards the enemy to liberate Bazaine (and avoid a revolution in Paris). Napoleon III was less in favour of the idea, but the regency council was strongly in support of it. MacMahon left the camp at Châlons regardless and headed for Metz to help Bazaine. But word soon filtered through that Napoleon III was about to be bottled up in Sedan.

26 and 31 August > Bazaine’s unsuccessful attempts to escape Metz.

31 August- 1 September > Defense of the village and bridge of Bazeilles by a French marine division. The naval infantrymen, who were taking refuge at an inn in Bazeilles, stood up to the Bavarian troops preventing them from taking the position. The Bavarian troops take out their frustration on the civilian population. The last French soldiers, or the ‘dernières cartouches‘ [the last cartridges – in reference to the soldiers at the inn who continued to fight until the last cartridge was fired], were spared by the Bavarians once the fighting had ceased.

1 September > Battle of Sedan, MacMahon injured. Napoleon III’s desire to be killed on the field of battle was been granted, so he returned to Sedan to raise a white flag in the hopes of saving his army imprisoned there.

2 September > The capitulation at Sedan: Napoleon III was taken prisoner by the Prussians along with 104,000 soldiers, 413 field guns, and 139 fortress cannons. On 5 September, the Emperor arrived at Schloss Wilhelmshöhe near Kassel, where he was imprisoned until 19 March 1871.

4 September > The Fall of the Second Empire and the proclamation of the Third Republic. A Government of National Defense was put in place. It was to be presided over by General Trochu, and made up of deputies elected from Paris including: Léon Gambetta (1838-1882) as Minister of the Interior; and Jules Favre (1809-1880) as Minister of Foreign Affairs. A Constituent Assembly was to be called.

Irène Delage and Marie de Bruchard, March 2020 (translation JR with PH)

SOURCES [in French]

• France Allemagne(s) 1870-1871. La guerre, la Commune, les mémoires, Paris, Gallimard / Musée de l’Armée, 2017, 303 p.

• L’âge industriel 1854-1871. Guerre de Crimée, guerre de Sécession, guerres de l’unité allemande, Brian Holden Reid, Paris, Autrement, coll. Atlas des guerres, 2001, 224 p.

• La guerre de 1870, François Roth, Paris, Fayard, 1990, 778 p.

• Dictionnaire de l’Europe. États d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Yves Tissier, Paris, Vuibert, 2002, 703 p.