The Congress of Paris was held in February 1856 after Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War. France, Austria, Piedmont, Turkey, Prussia, Russia and England came together at the congress to settle Europe’s diplomatic and geopolitical issues. Under the circumstances France, under Napoleon III (1808-1873), became an indispensable force of diplomacy, to such an extent that it was able to pressure the Austrian delegates into considering issues such as Italian unification.

However, a series of political crises during the 1860s – along with Prussia’s rise to political and economic power under King William I (1797-1888) and Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898: Foreign Minister and Confederal Chancellor of the North German Confederation from 1867) – weakened the French Empire considerably, which led to a border conflict between the two countries.

The rising power of Prussia

1862-1863 > The response of Prussia and Russia to the January Uprising (the Polish insurrection against Russian rule) revealed collusion between the two countries against Great Britain and, to a lesser extent, against France. All four countries were nominally tutelary guarantors the Polish entity, as per the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Napoleon III ‘s response was measured. With Prussia’s assistance, Russia used military force to put down the Polish uprising. ► Learn more (text in French)

January – October 1864 >The Second Schleswig War saw the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire fight Denmark. Krupp guns and the Dreyse needle gun played a major part in the Prussian war effort. The Treaty of Vienna of 30 October 1864, followed by the Gastein Convention of 14 August 1865, saw the two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein (the populations of which were majority German) ceded to Prussia and Austria respectively, and the duchy of Lauenburg annexed by Prussia. ► Learn more (text in French)

1865 > Meeting at Biarritz. Anticipating armed conflict with the Austrians, Bismarck held a meeting with Napoleon III at Biarritz to sound out Napoleon’s position. No commitment was made. ► Learn more (text in French)

1866 > The Austro-Prussian War

Empowered by its victory over Russia and by a secret treaty signed with Italy (6 April, 1866), Prussia waged war against the Austrian Empire, ruled by Emperor Franz Joseph I (1830-1916). Prussia opposed Austrian control of Holstein, and invaded the territory on 9 June. After some initial victories, Austria was defeated on 3 July at Sadowa, Bohemia, near the town of Königgrätz.

- 5 July > Napoleon III hesitated over France’s diplomatic position. He initially followed the advice of Drouyn de Lhuys (1805-1881), Minister of Foreign Affairs, who wanted to influence the outcome of the war by providing armed support to Austria. That evening, however, the Emperor was convinced by Eugène Rouher (1814-1884), Minister of State (in effect, “vice-Emperor”), and Charles de La Valette (1806-1881), Interior Minister, to push for mediation so as not to risk harming Prussian public opinion towards France.

- 26 July > Peace talks with Napoleon III.

- 23 August > The Peace of Prague. Austria was required to pay indemnities of 30 million florins to Prussia and accepted Prussia’s annexations of: the new province of Schleswig-Holstein; the state of Hesse-Cassel; the Duchy of Nassau; and the Free City of Frankfurt. Prussia took indirect control of the other territories by forming the North German Confederation, born out of the ashes of the German Confederation (the new confederation comprised the states north of the Main River). Austria lost political influence over the German territories and turned its interest towards Danubian territories (the Austro-Hungarian Compromise was signed on 18 June 1867). The southern German states, the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, the Grand Duchy of Baden, the Kingdom of Württemberg, and the Kingdom of Bavaria became independent but remained economically closely tied to their northern neighbours.

- October > The Kingdom of Hanover was annexed by Prussia. Veneto was ceded to the Kingdom of Italy with the Treaty of Vienna of 3 October.

In two years, Prussia gained 73,000 km² and 4.3 million inhabitants, going from a land area of 279,000 km² to 352,000 km², and increasing its population from 19.2 million to 23.5 million. France had a surface area of 551,000 km² and a population of more than 37.3 million (the population was 37.3 million in 1861).

Three European and International Crises

1867 > The Luxembourg Crisis, the same year as the Paris Exposition Universelle (April-October)

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg had been joined in personal union with the Netherlands when the Dutch king became its ruler. It had also become a member of the German Confederation and the German Customs Union (or the Zollverein), the latter primarily led by Prussia. In March 1867, William III of the Netherlands (1817-1890) accepted an offer from Napoleon III to purchase Luxembourg on the condition that Prussia agreed. In the eyes of the Prussian King Wilhelm I, such a transaction would be a casus belli on the part of France. Bismarck intentionally made France’s offer public, provoking a number of violent public demonstrations in German, Luxembourg and French territories. As it was the year of the Paris Exposition Universelle, Napoleon III sought appeasement and signed the Treaty of London on 11 May 1867. France abandoned all designs on Luxembourg, and the territory became a neutral state under the sovereignty of the Netherlands. Prussian troops had to withdraw from Luxembourg.

The rulers who came to Paris in 1867 for the Exposition Universelle, by Charles Porion © RMN GP, property of Compiègne

The rulers who came to Paris in 1867 for the Exposition Universelle, by Charles Porion © RMN GP, property of Compiègne

1867 > The failure of the Mexican Campaign (1861-1867), resulting in the execution of Emperor Maximilian I on 19 June 1867

In 1863, Napoleon III had encouraged the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian (1832-1867, of the House of Habsbourg-Lorraine, and younger brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I) to accept the crown of the Second Mexican Empire (1864-1867). The French emperor had intended to create a Catholic kingdom as a counterbalance to the power of the United States, a Protestant nation. From 1861 to 1862 France, Spain and Britain were unified in their intentions towards Mexico, as agreed at the Convention of London in 1861 (though for different reasons), but French troops eventually found themselves alone, and Mexican Republican troops eventually brought down the Mexican imperial regime and drove out French troops in February 1867.

1869-1870 > Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen offered the Spanish throne

There was a common accord throughout Europe that the great reigning dynasties would not put forward a member of their own family as a candidate for a newly vacant throne. In September 1868, Queen Isabella II of Spain was overthrown by the “Gloriosa” or “Septembrina” Revolution and forced to take exile in Paris. A constitutional monarchy was then installed by the Spanish Constitution of 1869. Napoleon III was in favour of a regency rule until Isabella’s son came of age (he was 10 years old), but Spanish members of parliament privately agreed to offer the throne to Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1835-1905), who was related to the Prussian royal house. Leopold had married Infanta Antónia of Portugal in 1861 and was the brother of King Carol I of Romania (chosen to rule by the Romanians in 1866). Leopold initially refused the offer in March 1870 but Isabella II’s abdication in 1870 brought the issue to a head, and Bismarck persuaded Leopold to accept.

3 July 1870 > The candidacy of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen for the throne formally announced.

Leopold was to be elected by the cortès on 20 July. This came as a great shock to the rest of Europe and especially to France, who believed that he had been ruled out as a candidate. King Wilhelm I of Prussia remained silent on the issue and showed no signs of disapproval.

French power under pressure

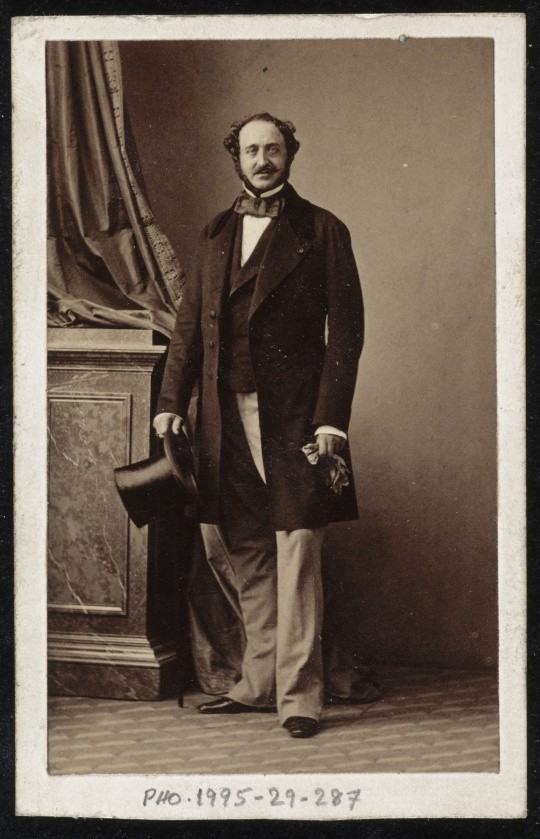

6 July > Agénor Duc de Gramont (1819-1880), who had been appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs on May 15, was questioned by the Chambers and had little choice but to make firm, if not belligerent remarks: “We would know how to fulfil our duty without hesitation and without weakness.”

The Duc de Gramont around 1865 by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) – Jean-Gilles Berizzi

The Duc de Gramont around 1865 by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) – Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Napoleon III and the Minister of Foreign Affairs instructed the French Ambassador in Berlin, Count Vincent Benedetti (1817-1900), to meet the King of Prussia in the spa town of Bad Ems (town website) to demand that the monarch guarantee, in no uncertain terms, his position against the candidacy. Meetings on 9 and 11 July amounted to nothing. Russia, Austria, Italy and Great Britain worked for conciliation.

12 July > Leopold Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen withdrew his candidacy. France was still anxious to get the Prussian King to guarantee his position.

13 July > Wilhelm I approved the withdrawal of the candidacy, but refused to provide the guarantees France sought. He sent a dispatch to Bismarck later on that evening. Bismarck, who was in the middle of dining with the Prussian Army’s chief of staff, Helmuth Karl Bernhard, Count von Molkte (1800-1891), manipulated the text to influence Prussian public opinion. He emphasised the improper manner in which the French ambassador had addressed the King of Prussia and published the story, both in the press and with posters in Berlin.

He also sent this edited account to all of the Prussian ambassadors in Europe so that other European powers would learn of the French ambassador’s behaviour. His idea was to humiliate France and to entice into a declaration of war. ► More about the Ems Dispatch (text in French)

14 July > The rush to war

- Morning of 14 July > The news of the the Ems Dispatch reached France. The Council of Ministers met with Napoleon III at the Palais des Tuileries at around midday. The Minister of War and Marshal Edmond Le Bœuf (1809-1888), believed that Prussia was already mobilising its troops (this idea was seconded by Gramont, the Minister of Foreign Affairs). The Emperor agreed to propose a decree to ready the military. The council swayed further towards appeasement as the meeting progressed, although they decided to call the reserves.

- Afternoon of 14 July> The two camps – pro- and anti-war – continued to argue, but the other European states were still pushing for appeasement and the formation of a European congress (agreed to by Gramont). British dispatches continued to call for restraint.

- Evening of 14 July > A new Council of Ministers met. Empress Eugénie (1826-1920) was present at this meeting, although she did not participate. The Council realised that both French and Prussian public opinion was baying for war (‘to Berlin!’ was the cry in Paris). The general prevailing pro-war sentiment in France and amongst the Emperor’s military advisors led to a new interpretation of the dispatch on the part of the ministers. They swung in favour of war. It was therefore through a ministerial, and not a diplomatic, channel that the decision was made.

- Around 22.00-23.00, Bismarck spoke with the British ambassador to Prussia, and made it clear that he was going to demand moral reparations from France for the behaviour of Benedetti towards the Prussian king.

Edmond Le Bœuf, calling card portrait, Unknown Artist © Wikipedia

Edmond Le Bœuf, calling card portrait, Unknown Artist © Wikipedia

15 July > In four consecutive votes, the legislative body voted to finance the war. A large majority of parliamentarians (including 32 republicans) were in favour, while Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) voted against, believing the war to be pure madness. Léon Gambetta (1838-1882) and Jules Ferry (1832-1893) abstained from the vote. “The diplomatic apparatus was unplugged” (Yves Bruley): French forces rushed into military action without the support of Austria and Italy, who were only be able to join the war in September (and wanted to ensure guarantees of their territories in the meantime). Paris, Vienna, and Florence were unable to reach an agreement in the few days before 19 July, most notably on the subject of the status of Rome and the Papal States.

19 July > France declared war on Prussia, with Napoleon III as commander-in-chief of his armed forces and Marshal Le Bœuf as Major General (Pierre-Charles Dejean, vicomte [1807-1872] served as interim Minister of War). While France was a long way from securing its alliances, Prussia made a deal with Tsar Alexander II (1818-1881). The Russian monarch secretly promised to support Prussia if Austria were to join an armed conflict in support of France. Over the following days the population was mobilised and prepared for the coming war. Napoleon III prepared his proclamation for the French people on 23 July before leaving Paris on 28 for the front in the East.

Irène Delage and Marie de Bruchard, February 2020 tr. JR

SOURCES

• France Allemagne(s) 1870-1871. La guerre, la Commune, les mémoires, Paris, Gallimard / Musée de l’Armée, 2017, 303 p.

• L’âge industriel 1854-1871. Guerre de Crimée, guerre de Sécession, guerres de l’unité allemande, Brian Holden Reid, Paris, Autrement, coll. Atlas des guerres, 2001, 224 p.

• La guerre de 1870, François Roth, Paris, Fayard, 1990, 778 p.

• Dictionnaire de l’Europe. États d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Yves Tissier, Paris, Vuibert, 2002, 703 p.