Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux: an obvious choice?

The imperial family’s request for the sculptor from Valenciennes is testament to Carpeaux’s privileged relationship with them. Carpeaux was introduced into the imperial circle by the diplomat Eugène d’Halwin de Piennes (1825-1911) whom he had met in Rome in 1859. In 1863, the Empress Eugenie appointed Carpeaux her chamberlain as did the princess Mathilde (of whom he created a bust in 1862). In 1864, the sculptor became the drawing and modelling master for Napoleon and Eugenie’s son the Prince Imperial and in the November of that year he was invited to Compiègne to take part in his first ever ‘Série’. This offered him a golden opportunity to make a good number of sketches of Napoleon, Eugenie and their son. In 1865, Carpeaux worked on a commission for a full-length statue of the Prince Imperial – by choosing to represent the child with his pet dog Néro, the artist added a touch of sentimental intimacy, avoiding imperial grandeur, that hit the mark not only with the imperial couple but also the public. The bust of Empress Eugenie in 1866, the original plaster cast of which is preserved in the National Gallery of Dublin, was to receive a much cooler response not only by the general public but even the Empress herself. A version in patina plaster is held at the Museum of Fine Arts of Valenciennes, the birth town of the artist.

Via the large number of commissions that Carpeaux received, (notably, the ‘Triomphe de Flore’ (The Triumph of Flora) for a façade of the Louvre, ‘La Danse’ (The Dance) for the Opéra, the ‘Fontaine des Quatre Parties du Monde’ (Fountain of the Four Quarters of the World) known as the ‘Fontaine de l’Observatoire’ (the Observatoire fountain)), Carpeaux reveals his mastery of technique, breathing extraordinary life into marble and bronze.

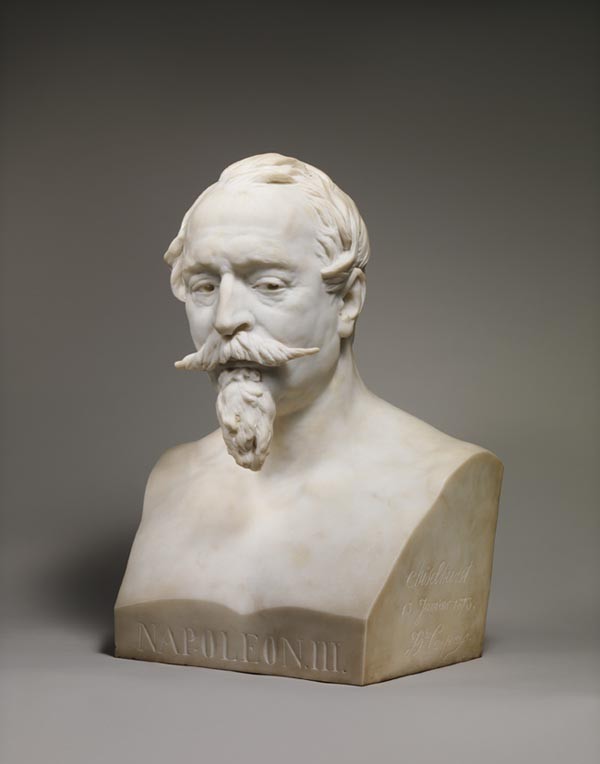

In 1871, the sculptor from Valenciennes was commissioned to apply his expertise to a bust of the fallen Emperor. During this time, Napoleon III was in exile in England at Camden Place, Chislehurst. Carpeaux arrived in London during March of the same year, not only so as to escape the Parisian Commune, but also to pay a visit to his old patron. Though he had been called back in January of 1873, Carpeaux was not to arrive until shortly after the death of Napoleon III and therefore was only able to take sketches of the Emperor’s corpse in the gloom of that January evening, whilst the servants held candles to make it possible.

An inscription of the right-hand side of the bust reads (front view) ‘Chiselhurst [sic]/13 January 1873/ JBte Carpeaux’, here indicating the date when the sketches were made. The bust having been completed in 1874. A version in patina plaster is kept in Valenciennes.

Looking into the Face of Pain

The final months of Napoleon III’s life were plagued by pain. The Emperor underwent several excruciating surgical interventions in a desperate attempt to remove gallstones. Despite having been trained in the tradition of antique busts, which emphasised the dignity and authority of the sitter, Carpeaux broke the academic rules and revealed Napoleon III in all his humanity as a suffering mortal. What he gives us is a naked, unembellished bust, his cheeks, sagging and sunken, his brow furrowed by pained anxiety, his gaze stricken, a man in the face of suffering and death.

It is possible that Carpeaux’s success as a sculptor was linked to the fact that he too was seriously ill. It is true that the sculptor had already grappled with the expression of suffering, notably with his ‘Mater dolorosa’ in 1870, (marble version acquired by the Clark Art Institute of Williamstown (Massachusetts, USA) in 2007; terracotta version (in French) held at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux; terra cotta version in Valenciennes). However, the artist’s suffering became even more tangible with his bust of Napoleon III: it was at this point that Carpeaux was nearing the end of his own life, suffering from bladder cancer. In 1874, the artist created several self-portraits (link in French) which were terrifying prefigurations of his own demise. Carpeaux died on 12 October 1875 at Courbevoie, in a house in the grounds of the Château de Bécon belonging to Prince George Babu Stirbei. His mortal remains were interred on 29 November at the Saint-Roch cemetery, Valenciennes.

A Mausoleum to Napoleon III

Whilst we will never know for sure, it has been suggested that Carpeaux wished to create a mausoleum in tribute to his benefactor. Such is the theory proposed by historian Alison McQueen, basing herself on the existence of a full-length statue of Napoleon III on his death bed, held at the Bucharest Municipality Museum.

Irène Delage, 9 December 2022 (English translation by Rachael Jefferies)

Bibliography

- Alison McQueen, Empress Eugenie and the Arts. Politics and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century, Farnham, Ashgate, 2011, p.348

• Anthony Geraghty, The Empress Eugenie in England. Art, Architecture, Collecting, London, The Burlington Press, 2022, p.271