► Learn more about the March to War

► Learn more about the Fall of the Second Empire

2 September > The Surrender at Sedan: Napoleon III was taken prisoner by the Prussians, along with 104,000 soldiers, 413 field guns and 139 fortress cannons. On 5 September, the Emperor was moved to Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, near Cassel, where he was imprisoned until 19 March 1871.

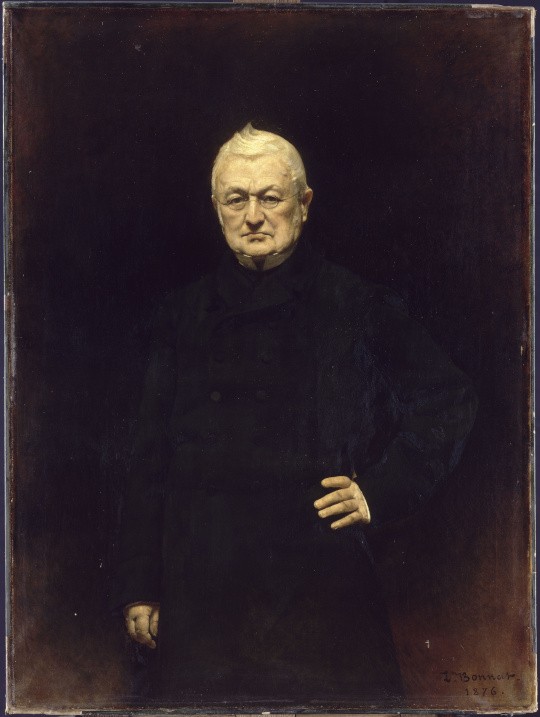

4 September > The Fall of the Second Empire and the proclamation of the Third Republic; The Government of National Defence was formed, headed by General Trochu, and made up of the elected deputies of Paris, including Léon Gambetta (1838-1882) and Minister of the Interior, Jules Favre (1809-1880); Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) turned down the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs. A constituent assembly was to be called.

The Third Republic continued with the war

1870: Diplomatic failures and military defeat

12 September > Adolphe Thiers began his diplomatic journey to garner support for the interim government, which continued to fight in the war against Prussia. His first stop was London. He travelled from there to Vienna where he stayed from 25 to 26 September, and then visited Saint Petersburg from 28 September to 12 October. He was unsuccessful in his attempts to forge alliances against Prussia, or to secure any form of international mediation.

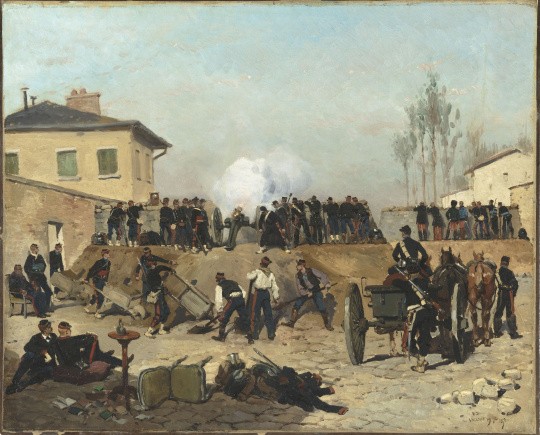

A sequence of defeats in Paris and on the Eastern Front

19 September > The Siege of Paris began. Prussian troops arrived from the east (Villeneuve-Seine-Georges, close to the River Seine), and from the south (Corbeil). The Government of National Defence relied on the city’s fortress defence system (which consisted of a ring of sixteen detached forts) to defend the east of the capital. These forts had been constructed by the Thiers government during the reign of Louis-Philippe and had not been reinforced in preparation for the war against Prussia and its allies. There was a weak point in this defence system between the two forts at the Châtillon redoubt to the south west of Paris. The Prussian army also advanced from the north (via Écouen) and west (via Pontoise). In abandoning the redoubt at Châtillon (on the orders of General Trochu) on 19 September General Ducrot’s French troops handed the Prussians a strategic vantage point on a silver platter. This vantage point was in an elevated position, which allowed the Prussian troops to continue the attack on Paris from the south-west. A French offensive was launched on 13 October, in a vain attempt to retake this stronghold.

19-20 September > Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) and Jules Favre held a discussion at the Château de Ferrières-en-Brie (at the site of the Château belonging to Joseph Fouché, and property of the Rothschild family). The Minister of Foreign Affairs (as appointed by the Government of National Defence) attempted to open up negotiations with the Prussian Chancellor, with no success.

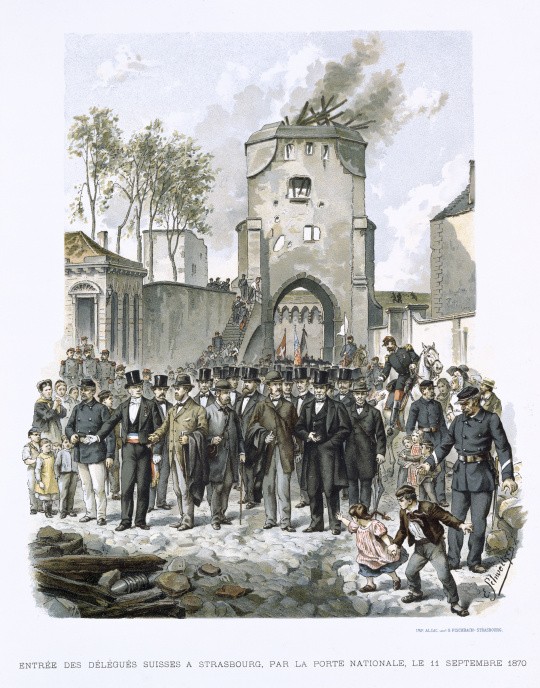

28 September > The surrender of Strasbourg. The city had been under siege since 16 August. A Swiss delegation in charge of evacuating civilians arrived in the town on 11 September and brought news of the defeat at Sedan. Under pressure from the city’s demoralised citizens, and in the face of the advancing Prussian troops, the town’s commander, General Jean-Jacques Uhrich (1806-1886), negotiated the surrender of the Alsatian city.

30-31 September > The noose was growing tighter around Paris. There was fighting in Chevilly-Larue and Choisy-le-Roi (both in the modern-day department of Val-de-Marne) between Prussian troops and French troops from the Paris region and the west of France.

5 October > Wilhelm I of Prussia established his headquarters at Versailles.

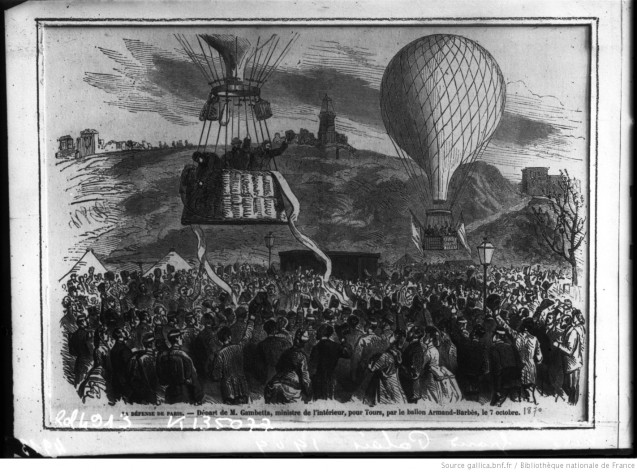

7 October > Faced with the Prussian advance, and after having ordered the withdrawal of troops to the east, Trochu’s government sent Léon Gambetta (who held the position of both Minister of the Interior and Minister of War) to Tours to organise the defence of Paris from outside the capital. A government delegation had been set up in that central western city in mid-September. The delegation included Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880), Minister of Justice, and Admiral Martin Fourichon (1809-1884), Minister of the Navy. With the capital under siege, Gambetta’s only way out of Paris was by hot-air balloon.

21 October > The Battle of Buzenval. French troops launched an offensive on the communes of Malmaison and Buzenval, to the south-west of the capital. They had some initial success, managing to push the Prussian troops back so far that the Prussian general staff were in danger of having to abandon Versailles. The Prussian troops were forced to withdraw into the woods, but took the area back after the French troops were ordered to withdraw. In a now famous encounter, troops from both sides came across each other unexpectedly at the Porte de Longboyau, with only a few metres between them. This was followed by a close-range exchange of fire. A week later, on 28 October, the Battle of Le Bourget took place to the north of Paris. It ended in failure for the troops of the National Defence due to a lack of reinforcements from Paris.

27-28 October > Bazaine surrendered at Metz. The city had been under siege since 20 August, and the news of the defeat at Sedan had taken its toll on the morale of both soldiers and civilians, who had already been weakened by the famine and from the effects of being cut off from the rest of the country. At the beginning of the month, Bazaine had forbidden the use of “papillons de Metz” [Metz butterflies], which were messages sent by balloon that allowed the inhabitants to communicate with the outside world. This had a disastrous psychological effect on the inhabitants of the besieged city. The capitulation was signed on the 27th, Bazaine surrendered on the 28th, and the Prussians took possession of the city and its military equipment on 29th. More than 120,000 French soldiers were taken prisoner. Having won the siege, the Prussian army could throw all its might behind its western advance.

30 October > Adolphe Thiers returned to Paris (which had been under siege for three weeks by this point), to resume negotiations with Otto von Bismarck at Versailles.

31 October > There was mass uprising in Paris and several towns in the Midi [the south], where news of the surrender at Metz and the growing Prussian threat to the capital had thrown the population into a state of turmoil. On the same day, Russia unilaterally repealed the provisions of the articles of the Treaty of Paris (signed on 30 March 1856) that concerned the demilitarisation of the Black Sea.

1 November > Talks between Thiers and Bismarck were held at Versailles. The Prussians now had the upper hand in both the east (after their victories over the French at Strasbourg and Metz) and at the gates of Paris. Bismarck had never been in a stronger position to make demands from the French government. The talks broke down once again on 6 November.

2 November > The start of the Siege of Belfort. Pierre Philippe Denfert-Rochereau (1823-1878), the commander of the city, opted not for a defensive strategy, but instead carried out repeated attacks on the Prussian troops surrounding the town to support the cannon fire coming from the city’s fortifications. The French situation worsened in December when the Prussians reinforced their artillery and advanced into a position from which they were able to shell the town.

The Army of the East, led by General Bourbaki, attempted to come to the city’s aid, but its advance was brought to a halt after a short-lived victory at Villersexel (Haute-Saône) on 9 January 1871, and it had to retreat to Besançon. Stopped in its tracks by its enemy forces, Bourbaki’s army withdrew towards the Swiss border.

© Paris – Musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais – Pascal Segrette

24 November > The surrender of Thionville. The Prussians troops who had held Metz under siege also cornered the city of Thionville, preventing communication between the two cities. They also cut off the supply route that ran to the city from Luxembourg. Thionville surrendered after two days of heavy bombardment.

A new German Empire was established in the wake of the Prussian Victory over the France.2nd half of November – beginning of December 1870 > While the negotiations between Prussia and France were not progressing, Prussia and its allies were also holding negotiations at Versailles. 23 November > An accord with Bavaria (whose delegation had arrived a month earlier) was established, followed two days later by another with Württemberg. 18 January 1871 > Wilhelm I was proclaimed Emperor of the German Empire, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

|

Resistance in the North, central France, and Bourgogne, but Paris and the East were lost

The North

27 November > The Army of the North was defeated at Amiens (Somme département). While maintaining its siege of Paris, the Prussian army concentrated the forces of its First Army to the north of the capital, from where it marched to Amiens then headed for Rouen. The commander of the northern region, General Farre (1816-1887), was unable to defend his position, and the Army of the North, commanded by General Faidherbe (1818-1889), did not have sufficient troop strength to resist the Prussian advance and was forced to retreat to Arras (even further north). The Army of the North had to give up all hope of reinforcing the Army of Paris: they held out at the siege of Péronne (Somme département) from 27 December 1870 to 17 January 1871 (the French army carried out one of its greatest feats during the Battle of Bapaume, near Péronne, on 3 January). The French troops made a last, vain attempt overcome the Prussian forces at the Battle of Saint-Quentin (Aisne département) on 19 January, 1871.

© RMN-Grand Palais – Hervé Lewandowski

Central France

1-3 December > The Army of Paris attempted to breakthrough enemy lines at Champigny in order to advance towards the Army of the Loire. The Army of the Loire had been assembled two months before (at the beginning of October) following the orders of Léon Gambetta, and was now focused on fighting the Bavarian troops who had forced it to abandon the city of Orléans on 11 October. It managed to retake the city on 10 November under the command of General d’Aurelle de Paladines (1808-1877), but its success was undermined by the end of the sieges on the eastern front; freed from the siege at Metz, Prussian troops turned their focus towards the centre of the country and advanced towards Paris.

2-4 December > The Army of the Loire was defeated at Artenay (Loiret département, south of Paris) and Loigny (Eure-et-Loir département, to the south west of Paris), and Orléans (also Loiret département) was retaken by the Prussians. The Army of the Loire had been separated de facto into two divisions and had to be reorganised. The two new Armies of the Loire would spend the rest of the war attempting to resist the relentless westward advance of the Prussian-Bavarian troops, who were moving in the direction of the Pays de la Loire. ► Learn more about the Army of the Loire (external French site).

© RMN-Grand Palais – Agence Bulloz

8 December > Under the threat of Prussian forces advancing towards the centre of France, the French government delegation relocated from Tours to Bordeaux.

Burgundy

In October, a small army was gathered under the command (despite protests from the French officers) of the Italian revolutionary Guiseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), to assist the Army of the East. Garibaldi had offered his services to the Government of National Defence. This small, ragtag army consisted of volunteer fighters who had been recruited in the Vosges and who had played a part in the resistance against the Prussians in Haute-Saône, Jura and in Côte-d’Or. Its objective was to retake Dijon (Côte-d’Or département) in order to split the Prussian army in two by occupying a strategic position near Belfort. The Prussians left Dijon on 17 December, and the city was occupied by Garibaldi in January. However, the Army of the Vosges had taken too long to recapture Dijon and did not manage to reach the Army of the East before the latter withdrew to Switzerland.

1871: Victory for the German Empire, and the Insurrection of Paris

5 January > The bombardment of Paris began. Krupp guns were brought to reinforce the Prussian artillery, and the troops began to bombard the south of Paris, intra muros. Throughout January, shells fell throughout Paris, from La Salpêtrière in the east to the Champs-Élysées quarter in the west. To the north of Paris, Saint-Denis and its surrounding areas (Drancy, Le Bourget, Tremblay) were under siege; to the west of city, the area from Mont-Valérien to Puteaux was subject to constant fighting as the two armies constantly captured and then lost the different zones.

19 January > Defeat for the French forces at the Second Battle of Buzenval. The Army of Paris launched one last offensive on 19 January, and the battle continued all day. The French troops were distributed across the command of Generals Ducrot, Vinoy and Bellemare, and they managed to force the Prussians into a retreat. They maintained their positions, although there were successive losses and recaptures of ground. Towards the end of the day, General Trochu was faced with the arrival of the artillery of the brand new German Empire, and ordered a French retreat, knowing that it would not be possible to resupply his ammunition. The falling darkness created the ideal conditions for a bloody German counter-offensive.

© RMN-Grand Palais (MuCEM) – Franck Raux

20 January > With this final defeat, Trochu sued for peace and abandoned command of the Army of Paris to General Joseph Vinoy (1800-1880), although he retained his position as president of the Government of National Defence.

22 January > Revolutionary activity swept through Paris. The demonstrators (including the Paris National Guard who had suffered the defeat of the Second Battle of Buzenval) refused to accept the surrender of their city and demanded an audience with the mayor, Jules Ferry (1832-1893). While the crowd was being addressed by Ferry’s deputy, there was an exchange of gunfire between the Garde Mobile and the National Guard, and five people were killed. After the day of insurrection on 21 October (see above), the developments of the 22 January sparked a rupture between the people of Paris and the Government of National Defence, the latter having made more arrests and then banned gatherings and the circulation of any publications that expressed hostility towards its actions.

23 January > Negotiations between Favre and Bismarck. The latter demanded the complete disarmament of Paris and its surrounding forts, planning for Prussian troops to enter the city imminently. The Germans also demanded a sum of 200,000,000 francs in reparations. Jules Favre managed to secure the delay of the German troops, as well as the preservation of the National Guard’s weapons (to keep Paris in order). Elections would be held to make sure that the peace treaty was ratified by a legitimate representative.

26 January > Jules Favre signed a 21-day armistice. It was published on 28 and 29 in the Journal Officiel [the Journal Officiel de la République Française – the government gazette]. The armistice did not concern the Army of the East, which was cut off at the Swiss border, nor did it take into consideration the city of Belfort, which was still under siege against the German army.

Le Monde Illustré [the Illustrated World] Wo722, 11 February 1871 © DR. Source : Le Républicain Lorrain

8 February > Elections for the Constituent Assembly were held. The results were heavily in favour of the royalists, and, to a lesser extent, the republicans. During a meeting in Bordeaux, the Assembly chose Adolphe Thiers as the head of its executive branch.

18 February > Denfert-Rochereau received orders to give up Belfort. In recognition of the resistance of the city, Belfort was not handed over to the Germans as part of the peace negotiations.

15 February > The armistice agreement (initially intended to end on 19 February) was extended.

26 February> The peace preliminaries were signed at Versailles. The next day, the preliminary treaty, which included the cession of Alsace-Moselle, was ratified by a majority of the new Constituent Assembly, with the exception of the 35 deputies from the territories to be ceded. ► Read the full text of the peace preliminaries

1-3 March > German soldiers entered Paris. They entered via the Avenue de la Grande Armée and occupied the Champs-Élysées quartier. The citizens cleared the streets of their own accord and took shelter in their homes. In order to keep the peace and avoid animosity, the Prussian soldiers kept away from the monuments in the area (the Louvre and the Invalides). They left the capital on 3 March at 11am.

10 March > The National Assembly left Bordeaux and relocated to Versailles, creating a stir amongst the citizens of Paris. In the midst of internal tensions, the Assembly announced through Adolphe Thiers that it had not decided whether to go with a monarchical or republican form of government, sparking yet more anger amongst Parisians. Members of the public formed the Central Committee of the National Guard, intending to defend the principles of the Third French Republic.

18 March> The people of Paris revolted against the army. Understanding that tensions were rising in the capital, Adolphe Thiers had wanted to get rid of the canons in the east of the city on 17 March, and intended to have the army store them in a location outside the city. The Parisians, along with some members of the Paris National Guard, opposed his plan, and they were joined by a number of soldiers. The Central Committee of the National Guard led them in a march from the east of Paris to the Hôtel de Ville. Thiers had returned to the capital a few days earlier in an attempt to calm the militant atmosphere, but was now forced to flee. The government took refuge at Versailles. Thiers was followed a few hours later by Jules Ferry (the mayor of Paris). Two army officers – General Claude-Martin Lecomte (1817-1871) and General Jacques Léonard Clément-Thomas (1809-1871) – were executed in Montmartre, accused of firing into the crowd. These executions exacerbated the already aggressive atmosphere amongst the people. The uprising was mostly contained in the east of the city, but the crowd occupied the Hôtel de Ville by late evening. The quartiers in the west Paris (which tended to be wealthier areas, and were closer to Versailles) did not join the uprising. The leaders of the uprising voted against marching to Versailles, and the wrestle for power between Versailles and Communards [the Paris Commune] began.

19 March > Napoleon III was freed and took refuge in Britain.

10 May > THE RATIFICATION OF THE TREATY OF FRANKFURT ► Read the full text of the treaty

France was ordered to pay reparations of 5 billion gold francs over the course of three years.

France lost Alsace, Moselle, part of Meurthe and the Vosges, as detailed in the preliminary peace treaty.

Citizens living in these territories who wished to retain their French citizenship were told to leave before 1 October 1872. ► Learn more about the Alsatian emigration:Le mythe du plébiscite par les pieds [the Myth of the Plebiscite by Foot] article by Bernard Wittmann, 2015 [French].

19 March > The Paris Commune began. The reconciliation between the mayors and deputies of Paris (who were acting as intermediaries for the insurgents) and the National Assembly at Versailles soured after the insurrection of the previous day. The insurgents declared their intention to secede and govern Paris independently of the government. This marked the start of the Paris Commune, and a new, ‘French vs. French’ chapter of the siege on the capital.

March – April > More communard activity was sparked in the provinces (notably in Lyon, Marseille, and Saint-Étienne).

21-28 May > The revolutionary experiment of 1871 came to an end in Paris, the last city to resist the government during the ‘Semaine sanglante’ or Bloody Week of May 21-28, when the army finally retook the city.

Members of the uprising set fire to state buildings (including the Tuileries, the Hôtel de Ville, the Conseil d’État, the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur, the Ministry of Finance, and the Police Prefecture) and around fifty people were executed, charged with conspiring with Versailles.

This Bloody Week saw a great number of the Communards die for their cause throughout the city (estimates vary between 8,000 and 30,000). Prison sentences were handed out to many of the survivors. The brutal finale of the Paris insurrection would leave and indelible and bloody stain on the social history of the capital.

1873 and the following years: The end of a war, and the end of an era

13 January > Napoleon III died in exile at Chislehurst, Kent (in the south of England).

16 September > The Germans left Verdun, marking the liberation of all the French territory that had been occupied during the war (excluding Alsace and certain parts Lorraine, as included in the Treaty of Frankfurt).

A deep anti-German sentiment grew in France, caused by its great war losses, as a sense of German national unity grew stronger with the consolidation of the Empire. The area of the Rhine continued to be a point of contention between both sides.

The consequences of the Treaty of Frankfurt would be felt fifty years later at the outbreak of the First World War.

1875 – > A republican government came to power in France: hopes of a return to a monarchical regime were slowly but surely abandoned throughout the second half of the decade (1870-1880). ‘Bonapartists’ imperial hopes were finally extinguished with the death of the Prince Impérial, on 1 June 1879.

Marie de Bruchard, April 2020

SOURCES

• France Allemagne(s) 1870-1871. La guerre, la Commune, les mémoires [France Germany 1870-1871. War, the Commune, the Memories], Paris, Gallimard / Musée de l’Armée, 2017, 303 p.

• L’âge industriel 1854-1871. Guerre de Crimée, guerre de Sécession, guerres de l’unité allemande [The Industrial Age 1854-1871. The Crimean War, the War of Secession, the War of German Unification], Brian Holden Reid, Paris, Autrement, coll. Atlas des guerres, 2001, 224 p.

• La guerre de 1870 [The War of 1870], François Roth, Paris, Fayard, 1990, 778 p.

• Dictionnaire de l’Europe. États d’hier et d’aujourd’hui [The European Dictionary. States of Yesterday and Today], Yves Tissier, Paris, Vuibert, 2002, 703 p.